Alberto Fujimori: does the end still justify the means?

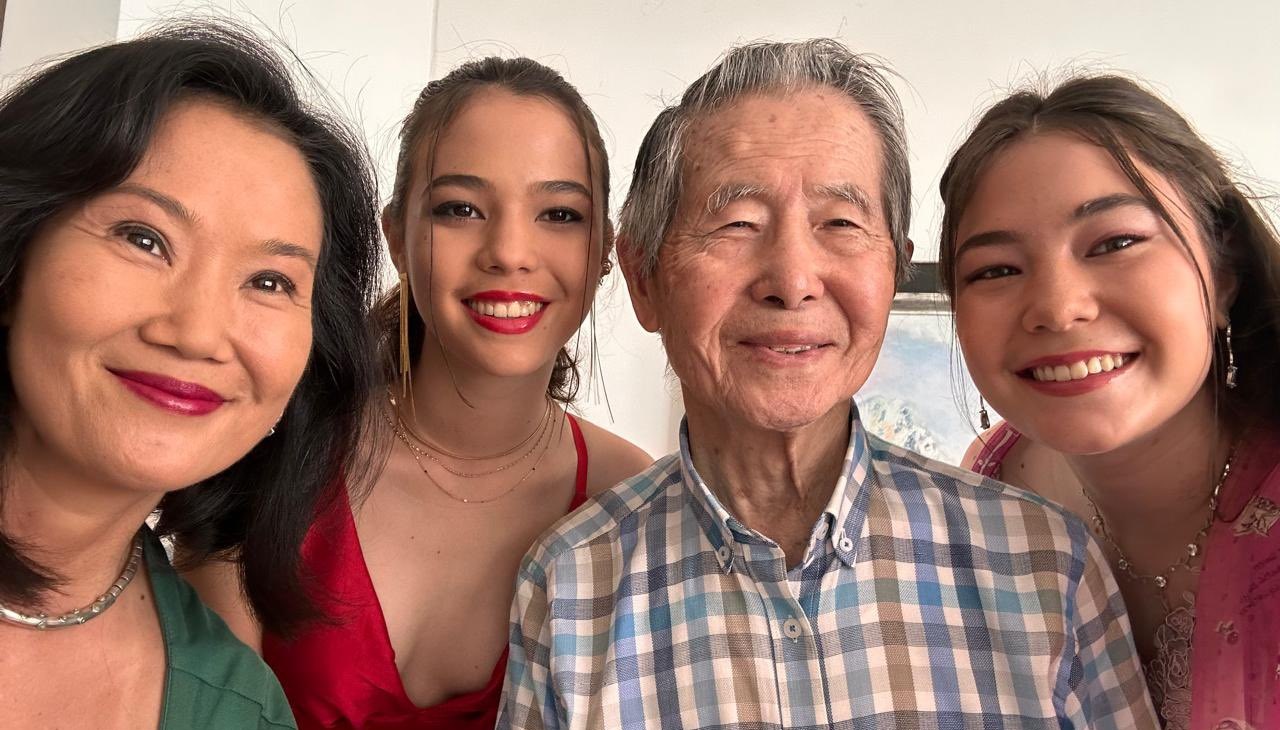

Latin America is full of stories of politicians who, having been at the height of recognition and popularity, end up hated and repudiated in their own countries. Alberto Fujimori is one of those cases. The former president of Peru between 1990 and 2000 passed away on September 11. His daughter Keiko broke the news to the world through the X network:

Después de una larga batalla contra el cáncer, nuestro padre, Alberto Fujimori acaba de partir al encuentro del Señor. Pedimos a quienes lo apreciaron nos acompañen con una oración por el eterno descanso de su alma.

— Keiko Fujimori (@KeikoFujimori) September 11, 2024

Gracias por tanto papá!

Keiko, Hiro, Sachie y Kenji Fujimori.

The story of Fujimori, of Japanese origin, ended after a long journey not only politically but also judicially, since he was convicted for severe human rights violations and corruption.

His regime was at first a balm for citizens desperate for the guerrilla violence of the Sendero Luminoso, which had in Fujimori its great contradictor and who finally defeated him: Abimael Guzman, the maximum leader of this group, was captured on September 12, 1992 and that meant a fall in the guerrilla group's capacity to generate chaos in the country.

CONTENIDO RELACIONADO

Fujimori's death is a good moment to reflect on the challenge for Latin America to achieve a path of political peace in which major issues can be discussed without the need to use violence or deteriorate the institutional framework. Fujimori seems to demonstrate that only an iron fist is useful in the pacification of our countries.

This is what happened in many nations in the region that have had authoritarian regimes in power as a formula for confronting guerrilla violence. The Machiavellian principle that "the end justifies the means" has thus been imposed. Fujimori achieved great results in the pacification of his country, but at the expense of high principles such as human rights and public faith.

Peace was achieved, but at the cost of the institutionality and morality of an entire people. Firstly, there were many collateral victims of his policies and, secondly, corruption took over many of the instances of power in his country. Proof of this were the famous "Vladivideos", which revealed the kind of practices necessary to guarantee "social and political peace" during his administration. That was the end of his government in 2000. Vladimiro Montesinos became the shadow of Fujimori's power and used every means to sustain the regime. Eventually, Montesinos, like Fujimori, was convicted of corruption and human rights violations.

The paradox that Latin American countries have not been able to resolve is that in order to achieve peace it is necessary to resort to all forms of struggle, including strategies outside the law. How will the region achieve true development in peace without always and at all times calling democracy into question? Latin Americans are still searching for the answer.

DEJE UN COMENTARIO: