[Op-Ed] Picasso’s Guernica Again

MÁS EN ESTA SECCIÓN

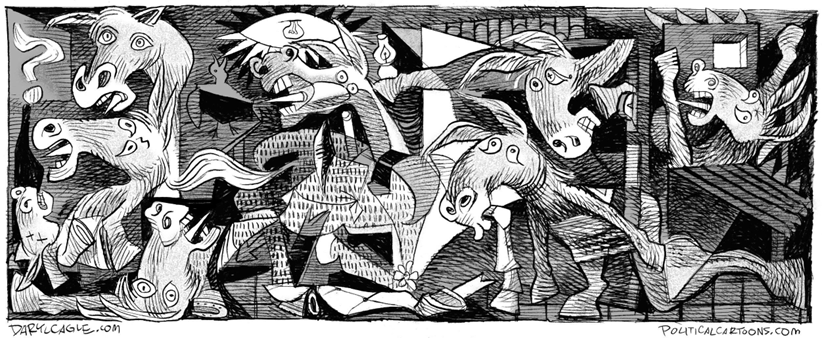

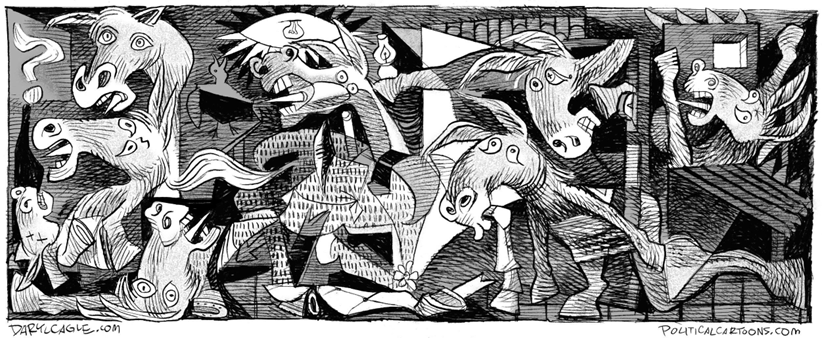

After the election last week, I saw a poignant political cartoon in The Philadelphia Inquirer by Daryl Cagle depicting a revision of Picasso’s Guernica. Instead of the animals together with the barefoot peasants, the fallen figures are all donkeys representing the democrats, without a doubt. The mother crying on the upper right is a donkey, the bull on the upper left representing Spain is a donkey; you get the idea. Only the black, white and grey palette, with touches of Pointillism and Cubist technique remain true to the original. The comparison of the Spanish Civil War with the defeat of the democratic party by Donald Trump is food for thought in any case, particularly for a Spaniard like me.

My family arrived to the United States in 1961. We landed in New York’s International Airport (now JFK Airport) to continue a few days later to Seattle, where my father was invited under the auspices of the Fulbright Program at the University of Washington.

CONTENIDO RELACIONADO

On the first day in New York City my father Juan Luis Alborg, as he had promised, took us to see the iconic Guernica at MoMa, where it was housed then. I recall that it was displayed atop a stairwell, all by itself on a landing, standing there, huge and somber. My father had told us that Picasso painted it in just three weeks to commemorate the bombing of the Basque town of the same name by the German Luftwaffe that supported Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War. More than one thousand residents were killed by the air raid and the painting represented Spain in the Paris International Exhibition of 1937. I’m sure my father analyzed it for us with his encyclopedic knowledge and critical eye for detail. I can only image what this painting must have meant to him, who fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War.

The Cubist painting measures 11.5 feet by 25.5 feet, and it is structured in the classical shape of a tryptic. On the right rectangle, a woman cries with her arms extended to an opening, trying to escape from the house in flames. On the left side, a mother – of the five human figures represented, four are women— screams with a dead child in her arms. On the middle triangle, one woman carries a light and the other drags her broken knee on the ground. The only man lays shattered with a knife and a flower in his hand, perhaps a peasant working in his field. The people are noncombatants since they are barefooted. The horse in the middle also cries in despair and the proud bull on the left could represent Spain. We know that Picasso paid tribute to the bullfight in several of his works.

Picasso decreed that this work could not be moved to Spain until a democracy was reinstated. He died in France in 1973, two years before Franco’s death, without ever returning to his country and Guernica remained at MoMA until 1981. I saw it again in Madrid at its first Spanish home, El Caserón del Buen Retiro (an annex of the Prado Museum). I loved its installation there, with two long-side corridors displaying the original etchings and sketches, many of them in bright colors. The mural seemed even more monumental in the large space of the exhibition hall. Spaniards of all ages stood in long lines to see it for the first time; many cried in silence, in their own emotional visits.

Guernica was relocated once more at the Reina Sofía Contemporary Art Museum in 1992. I don’t like it there as much as I did when it had an entire building to itself. In fact, I won’t be satisfied until Guernica is housed at the spectacular Museo Guggenheim in Bilbao, which incidentally, doesn’t have its own collection. Where could it be a more appropriate space for Picasso’s masterpiece than the capital of the Spanish Basque country?

DEJE UN COMENTARIO: