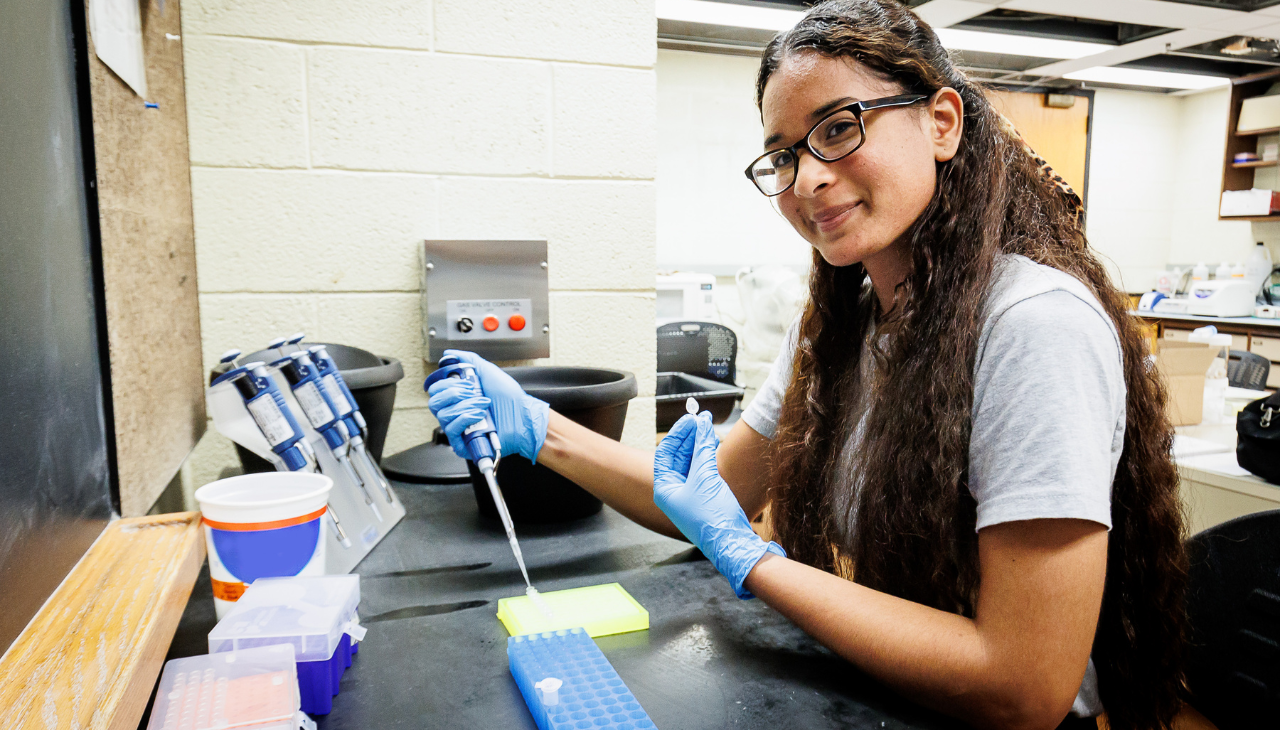

“Why am I here?” That’s the feeling many Latino students struggle with in higher education

When Frida Sanchez-Rosalino, a sophomore Spanish Education student at Elizabethtown College, arrived in the United States three years ago from Mexico, she changed the way she identified herself. She wasn’t just Mexican anymore, she was also Latina, she said.

A difficult process at first, it took her a while to adapt to the new culture, language, food and school. Specifically in high school, where she attended an institution with not many Latinos, she felt she didn’t belong there. Also, struggling with learning English sometimes was a challenge for her to share ideas and thoughts, she felt incapable and insecure about herself.

Her ‘American dream’ ended up becoming an ‘American nightmare’, as she described.

Driven by her childhood dream of attending college, her mentality eventually changed and she decided to keep following her goals in higher education. A year ago, she graduated from Olney Charter High School — which is a part of the College Access Program in partnership with the Philadelphia Education Fund (PEF). She explained that through this program, her teachers helped her better understand the college application process, from writing essays to getting financial aid.

“Being a member of the program made me realize that I was college material, and that I would be the first in my family to have the opportunity to attend college,” she said. “I hope that my sisters someday have the same opportunities as me.”

Just like Rosalino, many other Latina students experience the “fish out of water” feeling; or better said, when they don’t believe in their capacity to be successful. Self-sabotage, self-doubt, and lack of representation are among the factors that make these Latina and first-generation students feel like they don’t belong in higher education institutions.

According to a Forbes Brasil article, a study done by the University of Georgia showed that 70% of women interviewed felt like a fraud in the workplace. Representing the impostor syndrome feeling, this term was created in 1978 by two Georgia State University psychologists. The study indicated that the more successful women get, the more insecure they feel.

In higher education, Statista stated there were over 2 million female Hispanic students enrolled in American universities in 2020. On top of that, Latinos are more likely to be first-generation college students than any other racial or ethnic group, NBC News stated. Around 44% of Hispanic students are the first in their family to attend college.

For Rosalino, the impacts of the impostor syndrome on Latina women in college can affect their self-esteem and academic performance as students. Because of the stigmas in the community, the expectations and pressure towards Latina students are different. Although it is not the case in every family, she explained sometimes there is no culture of going to school because of economic circumstances — caused by the inequality of underrepresented groups.

She added by saying Latinas also suffer gender discrimination, which affects the opportunities that are presented to them. Specifically in the case of first-generation college students, the pressure to meet parental expectations could also be a determinant factor of impostor syndrome.

Rosalino was aware she had impostor syndrome because she was afraid to speak in class.

She didn’t like her accent, and felt “dumb” when speaking English. She found out about the term on social media, and talking with her friends who shared the same thoughts, feelings and experiences was important for her.

Liza Rangel, Lead College Access Coordinator at PEF, says she doesn't like to blame the students for feeling that they don’t belong or aren’t good enough for an institution. Instead of understanding it as a systemic issue, the official definition of impostor syndrome phenomena interprets it as an individual dilemma.

“It blames the student for not knowing things that they simply don’t have the access to,” she added.

Rangel, the daughter of Mexican immigrant parents, attended New York University, as an undergraduate, and the University of Pennsylvania, as a graduate student. She recalls the only experience she had with a Latina professor in college was at a Latin American studies class. Other than that, she has never had another Latino professor throughout her years in academia. It was important for her to see another Latina in that position, and she believes the class experience would have been different if it wasn’t taught by her.

“I got a lot out of that class because the professor was able to not only talk about the readings but also share anecdotal real experiences,” Rangel added. “Students need to see themselves represented by professors and counselors.”

A FISH OUT OF WATER

Allison Kelsey, Senior Manager of Communications and Scholars at PEF, described what impostor syndrome is by saying even though you perform well in school, and have good test scores to get in, you get the feeling that you shouldn’t be there. “Somehow I've gotten in here by accident,” she said.

At PEF, Kelsey explained that students usually attend schools with the lowest graduation rates in Philadelphia. They are hard workers and perform well in their class in institutions that are generally underperforming and end up not having many advanced placement courses or other opportunities that students from schools from all over the country do.

Besides academic differences and often attending predominantly white institutions, these students have to face cultural and language barriers, as many of them have Spanish as their first language or grew up listening and speaking it often — especially in the Philadelphia area, where there is a huge Latino community. Although PEF likes to highlight this as an advantage, often students feel out of place at institutions if they have an accent and others ask them where they are from, neglecting the fact that they were actually born and raised in Philadelphia.

CONTENIDO RELACIONADO

For Latinas specifically, Kelsey highlighted how sometimes parents are reluctant to let their young daughters go to institutions that are considered far away from home. If they eventually do attend those, it can add to the idea of having made the wrong decision and overreaching, instead of just settling for what they knew.

“But in the end that’s the point of college, to branch out and grow, and get to know different people,” Kelsey added. “And sometimes some level of discomfort is part of the growing process.”

PEF makes an effort to remind students that they have something that the majority of the other students don’t have and that their experiences are unique and valued. It can be hard to believe in that when people are often questioning your truth or if you can’t blend in, but Kelsey advises on the importance of finding a group and creating connections. Students find support in larger groups such as local chapters of national Latino organizations in their colleges.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

When Rosalino first arrived at Elizabethtown, she had the feeling that she didn’t fit in there — as the majority of the students were white. When she and her friends found other Latinos, Rosalino was able to develop a sense of belonging to a community. She likes to share her customs and traditions, and student organizations are a great way to keep cultures alive.

At the student body level, creating organizations seems to always be a good alternative for students with similar backgrounds to get together. Rosalino likes to highlight the importance of making changes that seem needed. She, along with her friends, for example, founded the ‘Making Her Story Club’ for women, empowering and recognizing the value of women on Elizabethtown campus.

For Rangel, she highlights the importance of finding mentors on campus. When she was able to connect with professors, she got a lot more from her program. Especially as a first-generation college student, she explained she didn’t know some logistics that her colleagues who had families who attended university or other connections knew. Buying used books and going to office hours, for example, were some of the things she learned along the way.

“I think Latina students just need support in higher education,” she added. “It is great to admit these students in prestigious universities but it is a disservice to not give them access to resources that would allow them to graduate.”

Other than that, educating people about what impostor syndrome is and creating programs and centers not only for Latina students, but also for students of color, low-income and first generation students, seems to be a shared solution between the interviewed. These safe spaces to discuss social justice issues and appreciate diversity are important for underrepresented groups' advocacy. It helps them with the process of adjusting to college life, feeling part of the community, and thriving.

“It is time for Latinos to start believing that we are capable of achieving whatever we set our minds to,” Rosalino added. “It is time to support each other and make our community a safe and better place.”

Kelsey also highlighted how institutions that specially reach out to students of color should make an intentional effort to help them adjust. It is essential to create resources for this community to feel welcomed. At PEF, for example, they have college access programs in six different high schools in Philadelphia, where the majority of the students are Spanish speakers or have a Latino heritage. PEF makes sure to have Spanish speaker counselors so students can relate, especially about their experience in higher education as Latinos.

Feeling that you belong to an education institution is essential for academic success, but doesn’t necessarily need to mean that you have assimilated into the broader group, Kelsey said.

“You can still have a distinct background,” she added. “If you feel that you are embraced by the university and promoting [racial, ethnical and socioeconomic status] diversity is part of its values, then you are going to think that you belong.”

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.