The importance of Latino LGBTQIA+ diversity in higher education

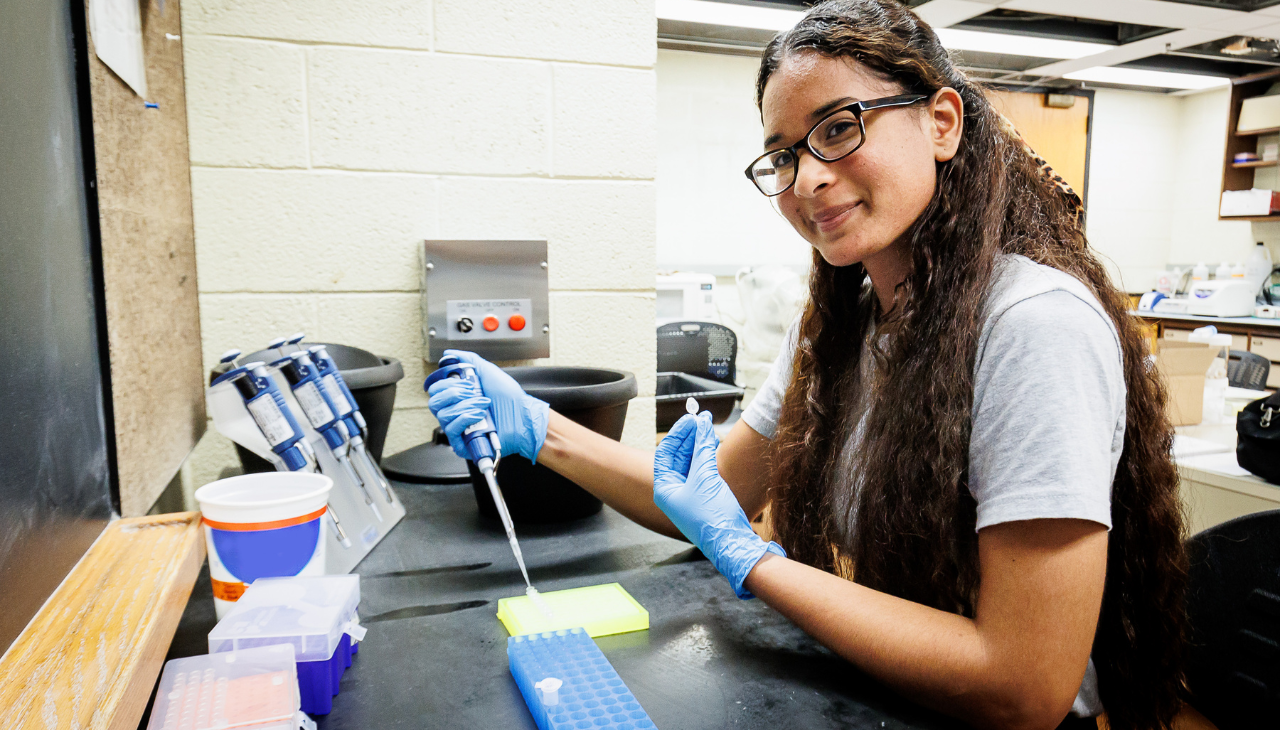

Latinos have been taking over higher education institutions, as the enrollment numbers of this community were growing until 2020, when the pandemic happened. As a result, according to Excelencia in Education, this group represented 17% of degree completions overall, between 2019-2020.

It is an understatement to comment on the importance of including underrepresented groups, from all races and ethnicities, in order to promote diversity in the educational environment. However, not as much commented, is the importance of sexual orientation inclusivity in colleges and universities.

Latino members of the LGBTQIA+ community are often not mentioned in studies about education, but according to UCLA School of Law Williams Institute, 22% of this adult population have a college education.

Considering the historical oppression not only Latinos, but especially the ones from the LGBTQIA+ community, have suffered throughout the years; Al Día News contacted Omar Martinez, former Associate Professor at Temple University’s School of Social Work, to hear his thoughts about the environment LGBTQIA+ Latino students face in higher education.

Born and raised in Cuba, Martinez moved to the United States when he was 17 years old. Since then, he has gone through many higher education institutions, getting knowledge and researching on the fields of political science, sociology, Latin America studies, law and public health.

From undergraduate to a dual JD/MPH degree, he attended institutions in different parts of the country. Starting South and then reaching North, without excluding the midwest; he attended University of Florida, Indiana University and Columbia University. Despite the many variations among them, the one thing in common was that Martinez has never seen himself represented by his professors in any of these schools.

During his last year in high school though, he had the opportunity to have as a role model a Lesbian Latina counselor — to which he attributes his professional career success until this day. With her mentorship during his one year in high school, strategically helping him choose classes; he credits to her the fact that he was accepted at the University of Florida, without even knowing how to speak English.

“I remember the unique connection that we had as both minorities, with different and beautiful identities,” Martinez said.

After working for seven years at Temple, Martinez is now off to a new position as an Associate Professor in the sunshine state, at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine. He says he feels embraced by his previous and new work environment, and colleagues because of the appreciation shared for his work with HIV, undocumented Latinos, and sexual education.

Faculty of color and of the LGBTQIA+ community like himself, bring this diversity to the work environment, with new research ideas and perspectives. They add value to academia by having their communities engaged in the research question they are working on — by giving the responsibility to the community to frame and develop it.

“One of the things that we, gay Latino researches, bring to the table is our understanding of the communities we intend to serve and our connections to them,” he added.

Besides the fact that Black and Brown researchers endorse racism and discrimination in these spaces that are predominantly, depending on the institution, very homogenous when it comes to race, gender and diversity; there are other barriers that this community faces.

When highlighting some of the challenges, Martinez points burn out as one of the most important. He shared that many faculty of color feel pressured to serve in many different committees which can impact the work of LGBTQIA+ Black and Brown researchers. He explains that in order to get a promotion, researchers need to bring funding, but because this community is so overwhelmed, it often affects a positive outcome.

CONTENIDO RELACIONADO

“We need to do better in creating an environment to really support this community as researchers,” he added. “We need to change the promotion guidelines to account for the service we do, especially the community engagement research; and have it valued in the promotion process.”

LGBTQIA+ Latinos in the higher education environment often experience impostor syndrome, but Martinez likes to point out how it is the system that makes this happen. The feeling of never doing enough or being valued for the scholarships you have is a structural problem.

“It is not individual, it is not on us,” he added. “It is the pressure that we have.”

In order to promote a better work environment, Martinez believes institutions should first focus on equity compensation for the work done — even between Latinos, when talking about gender. Some institutions are starting conversations about changes, but it is a slow process. There is still a funding hierarchy, where federal is higher than foundation grants, Martinez says.

Valuing the work LGBTQIA+ Black and Brown researches do goes beyond money, and institutions should spread the word about what this community has been doing by writing about its achievements. From small to big accomplishments, being valued by the institution you are working for is what makes you want to stay.

In his personal experience, Martinez has always felt valued by his colleagues during the time he worked at Temple University. He believes the school of social work tends to be more welcoming to diversity, and he is now excited for the future back in the state where he started his academic career.

“You must go to places and institutions that really support your scholarship and value you not just in words, but also financially and with acknowledgement and actions.”

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.