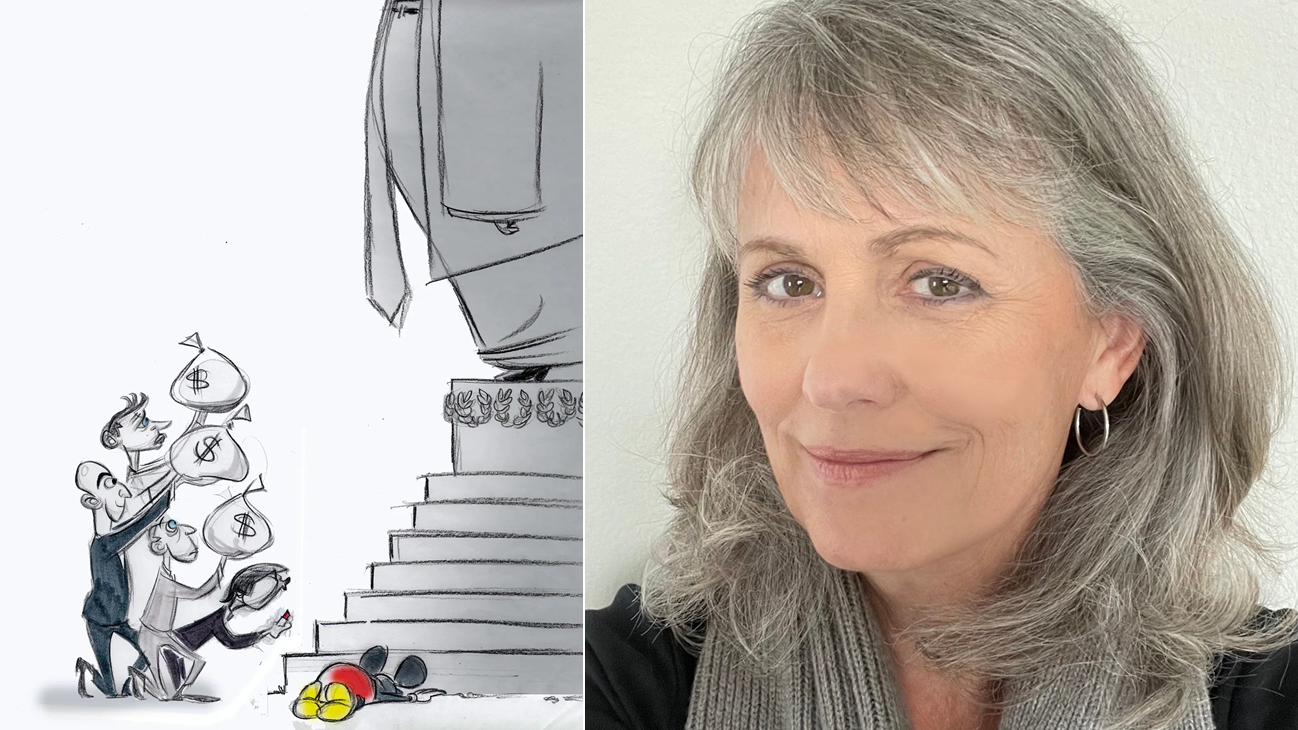

Finding dignity in the loss. The living reality for Latinas running for City Council.

Latinas continue to build political power despite continued losses.

The moment Cherelle Parker addressed the public for the first time after making history on election day, she was asked about ranked-choice voting and whether it was time that Philly adopted novel methods of electing city officials amid increasingly crowded races.

It was the last question Parker would respond to before disbanding the press.

“I will look at other prescriptions in the future,” Parker said, “but right now, this is the environment that mayors in the city of Philadelphia have competed under for the past 100 years.”

Parker, whose victory was synonymous with the triumph of an institution, said she trumped the system. Fair and square.

“Everyone doesn’t get a trophy. Your dignity doesn’t come from getting a trophy. Dignity comes when you work hard in a race… in a race of any kind. No matter what it is. And that prescription is one that I support.”

For Latinas in city politics, there is neither dignity in the current prescription nor trophies waiting at the finish line. That doesn’t stop them from laying their reputations on the line to fight tooth and nail for a seat in any elected office.

Joyful campaigning

Luz Colón is a relentless optimist. Anywhere on the campaign trail, Colón’s smile stretched ear-to-ear as the timbre of her voice rose octaves within the delivery of one sentence. She referred to supporters in her orbit as “my friend,” wearing the same grin.

Since her launch for City Council at-Large at a Colombian-owned real estate office in South Kensington, Colón, 44, promised to run a joyful campaign, hoping to revive the fun in politics and voting.

At forums and events, Colón spoke gleefully about her plans to aid Council in tackling crime and bringing her years-long state government experience to City Hall and return to her Philly roots.

But that wasn’t the case at Cousin’s, a supermarket best described as a bespoke Latin grocer with a pantry exhibition of sauces and seasonings imported from all over the Caribbean. Instead of Puerto Rico or the Dominican Republic, the farthest travel shoppers weathered was a trip from Norris Square.

It was at Cousin’s where Colón broke down for the first time while circulating petitions “because I knew it was bad, but I didn't know it was that bad. To the point that nobody even wanted to sign a petition.”

Is she viable?

The road laid out for Colón was complex but not unrealistic. Her choice to pursue an at-Large seat in Philly City Council meant her campaign needed to be citywide. And similarly to other Latinos vying for a spot on the ballot, the expectation was that she would motivate a new sector of voters considered politically disengaged.

The former, often the only topic made relevant to Colón’s campaign, grappled with the latter, a necessary step to get votes. Her bid also required masterful relationships, an ability to fundraise, and obtain endorsements to become a viable candidate.

Forming those partnerships early on is critical to ensure a candidate’s name circulates frequently among insiders who will eventually carry those prospects to the mainstream conversation.

Despite having deep relationships with mainstream Philly Latinos, Colón fell short of obtaining name recognition and raising enough cash to run a competitive operation. She was endorsed by Maria Quiñones Sánchez, a political rebel whose reputation helped protect the only seat on Philly City Council with a Latino representative, two weeks before the primary.

Ángel Ortiz, the only Latino to serve as at-Large City Councilmember in the body’s history, was present at Colón’s launch, hoping she would meet the moment. Yet it’s unclear whether Ortiz had any pull in the months that followed.

Running for office in Philly’s Latino sphere requires protecting the seats currently held by Latinos, as Quiñones Sánchez did with District 7 when she appointed her successor and longtime protégé, Quetcy Lozada, who won the primary nomination.

“What caught me by surprise was that perhaps I had it in my mind that maybe, in some way, we could’ve been supported…” Colón said, her thoughts trailing with the breeze. “I don't think that Latinas are supported in this realm as much as they should. It's hard.”

A good lesson

Colón debriefed her experience from Lighthouse, a nonprofit serving the North Philly community, and where she serves as a member of the board. She’s visited Lighthouse more now that she has more time on her hands after dedicating the previous months to the campaign.

She visits a pig named Lulu, a resident at Lighthouse whose tail wagging boosted when Colón called out her name. Those small moments brought her a shred of joy. An aggressive downwind flowed through the field.

North Philly is home to Colón. The wind returned a sense of familiarity to her.

“It's a good lesson,” thought Colón of her support. “Because just imagine if they would have made it easy for me that way, I wouldn't have been as strong as I am today, or appreciate the way that everything has turned out for what it is and how it turned out for me right now.”

Colón looks forward to finishing her degree and taking day courses. She didn’t get to revel in the college campus experience as a kid.

The Latino vote

2023 was Érika Almirón’s second shot at City Council at-Large after unsuccessfully pursuing a bid in 2019, the previous cycle.

From her home in Northwest Philly, a three-story house that she’s owned for 13 years, Almirón takes her loss in stride, deeply proud of the coalitions she’s built over her life.

RELATED CONTENT

“We built something that was visionary. And so was this one, but I think that I really wanted to make sure this time that we included a base of Latinx people who were involved, who were a part of the conversation, not that it wasn't the last time, but I don't think that that was the focus,” Almirón said over coffee.

Chasing the Latino vote is a great risk for political hopefuls, save a few incumbents. Most focus on wards in District 7, which is predominantly Spanish-speaking, but turnout is a persistent problem buoyed by gaps in language and culture.

There are Latinos spread across Philly, and ward turnout in other regions with dense Latino populations showed strong voter participation. Still, power is concentrated in the seventh councilmanic district, starting in Fishtown and progressing north through Norris Square, Fairhill, Kensington, Juniata, Feltonville, with parts of Frankford and Oxford Circle in the Northeast and then bordering Hunting Park in the West.

“I think Latinos are going to be one of the hardest base of voters to control. And it's not about controlling the Latino vote. It's about inspiring the Latino vote. So I think when we move to a place where any either party or those in power, move to inspire voters, rather than control voters, you're gonna have a different outcome,” said Almirón

The Democratic Party is a far cry from achieving that endeavor. No bilingual mailers or Spanish-language voter education multiply the challenges voters face when electing officials.

Bob Brady, Chairman of the Democratic party, admitted efforts could be made to reach Latinos but did not specify how at a political brunch hosted by Parker.

“I’ll believe it when I see it,” Almirón responded to the notion.

Almirón finished her campaign garnering more votes than her last run. Though she said it’s just the beginning of building what she described as Latino political power.

“The fact that we don't have three City Council people is actually unjust in the city, given the makeup of how many Latinos live in the city, and they'll pigeonhole us into one neighborhood.”

Prepping for what’s next

Almirón is already thinking about the next four years. “I’m probably going to have to start fundraising now,” she said.

“I'm a daughter of immigrants. I don't come from a political family. I don't come from money. I can't just buy my seats, dinner. I mean, I can't just throw half a million dollars into a campaign,” she said.

That means her alliances would need to be solid, while risking running afoul of her own principles. During the election cycle, Almirón gathered a mixed coalition — progressive groups like Amistad and Reclaim Philly supported her bid.

She also had the backing of District Attorney Larry Krasner, who credited Almirón for being consistent in different crowds. It’s a speech he repeated again at Sheriff Rochelle Bilal’s reelection launch.

Other groups who weren’t aligned with organized progressive groups, but who considered themselves progressives — including Quiñones Sánchez and her following — backed Almirón.

“What makes it difficult is that as much as we don't have a political home, and we're building that. People want you to belong to their political home in their ideology, and so maintaining a sense of independence is actually the goal.”

Almirón is looking forward to resting, tying loose ends related to her campaign, and continuing to build political power for Latinos.

LEAVE A COMMENT: