Cherelle Parker plunged into local politics at 17 and never looked back

Parker’s mayoral campaign is chock full of lessons learned over the course of the defining moments in her life and career.

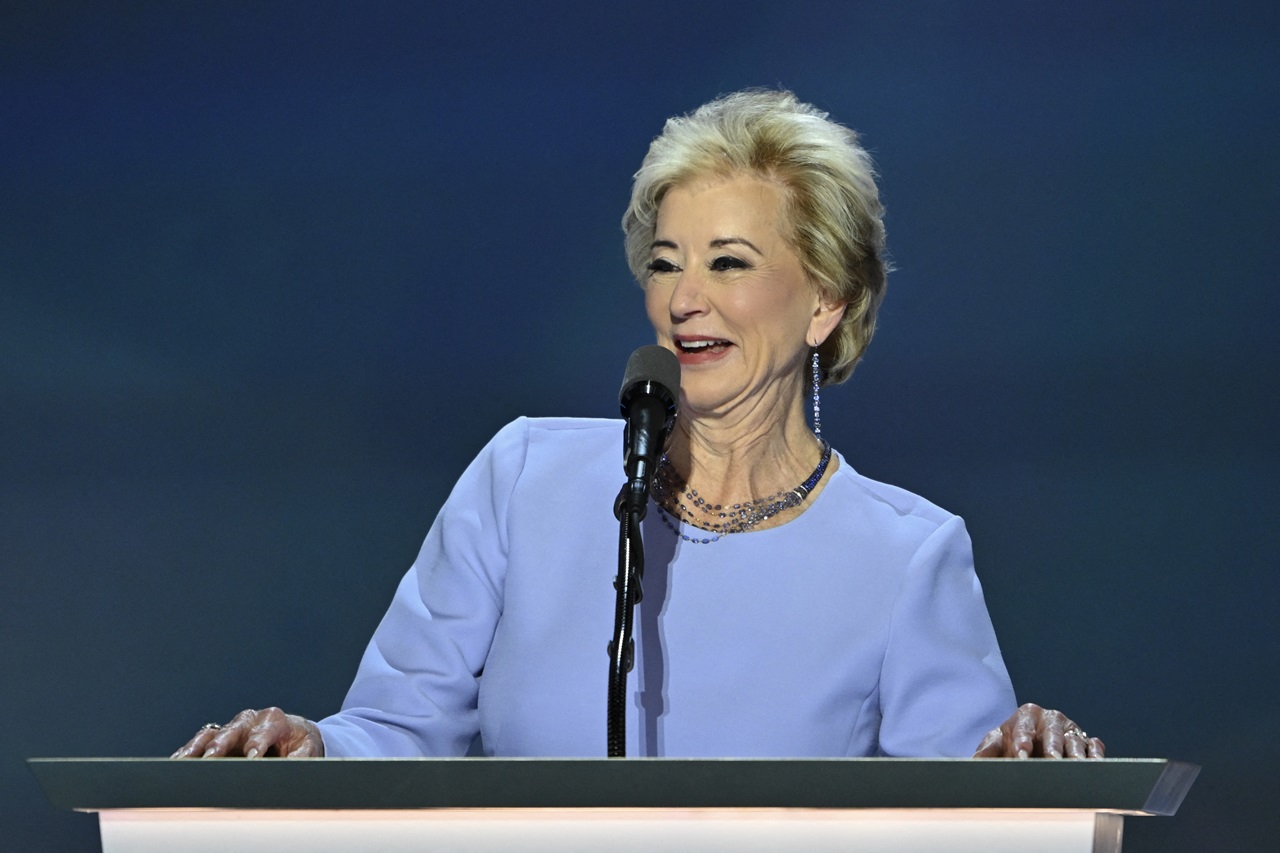

Everybody knows the story of how Cherelle Parker got her start in politics.

Two oratory competitions — both of which she won first-place awards for — caught the attention of the late City Councilmember Augusta Clark, who later introduced her to Marian Tasco, who eventually became her mentor.

Clark had been the first Black Democratic woman to serve in an at-Large City Council seat in Philly.

“Philadelphia's incestuous. Everybody came from a powerful political family. They knew someone or mother or father was extremely powerful,” Parker said.

“I was a little Black girl growing up in poverty, you know, with no dad in my life, my mother deceased, raised by my grandparents, and they decided: ‘we see something in you.’”

Parker, fully aware of her perception as a candid yet vigorous speaker, said that “if you started where I started from in life, and you had a village or community, a city that deposited so much in you, you wouldn't know why I'm so passionate about what I do.”

After serving in Tasco’s office in several capacities, Parker moved to Harrisburg, representing the 200th legislative district, which covers the Mt. Airy neighborhood, and stayed for 10 years in Harrisburg before heading back to Philly.

While in the state capital, she garnered a reputation. A “get-it-done Democrat” described as politically savvy, often presenting her political resume as a means of walking the talk.

Some of her legislation includes the Philadelphia Tax Package, a method to collect delinquent property taxes and allow for payment in installments, and redirecting that funding toward LOOP, a tax relief program for residents who fell within the homeownership requirements.

She helped to motion Act 75 in 2012, a statute in the state judicial code that permitted experts of sexual assault to testify and assist courts in understanding “the dynamics of sexual violence, victim responses to sexual violence and the impact of sexual violence on victims during and after being assaulted.”

When she returned to City Council to represent the 9th Councilmanic District, she championed legislation that addressed infrastructure, homeownership, and a training program for small business development currently run by the Community College of Philadelphia.

Parker also served as the Majority Leader during her council years. Now, she faces a highly competitive mayoral election with nine other candidates attempting to convince Philadelphians why they should vote for them.

Small business

When Parker talks about the median small business owner in Philly, she’s referring to those “who have a significant amount of skin in the game because they are leasing, renting or owning brick and mortar establishments.”

Citing a group of Drexel students with an entrepreneurial spirit, Parker said that while there are buzzing ideas, the lack of investment outweighs the ability to grow and scale businesses.

Parker, a venture capital fan, said she would leverage private equity investments into small businesses, “carving out and developing a very specific plan” by engaging Community Development Financial Institutions to fund Black and Brown entrepreneurs.

The idea was to find ways to involve the private sector. The city has dabbled with CDFI programs in the past to kickstart the economy amid the COVID-19 pandemic, with goals focused on minority-owned businesses.

But previous reporting showed that a similar initiative by a coalition of business and civic leaders in Philly fell short of meeting the needs of minority businesses.

Philly is also notorious for imposing onerous roadblocks for investors and is considered an unfriendly city to do business in because of the amount of red tape and extended periods of time it takes for different boards to go through approvals.

“I think local government does a super poor job at it,” Parker said, responding to questions about City Council’s sea of regulatory requirements.

“We have to be more efficient. And we can build those models, but we can't be afraid of change. And we've got to communicate with our workforce.”

Parker said she would remain open to the idea of modernizing the current process and described a “one-stop shop” model for business owners to reference, as opposed to obtaining documents individually from city offices.

“We have to stop thinking that we need everything done via legislation. We have a strong mayoral form of government. If I thought that the only thing we could do to move Philadelphia forward was to enact it through legislation, I would still be a member of the City Council,” Parker noted.

RELATED CONTENT

She leaned toward enacting an executive order to kickstart a digital transformation in City Hall, though the details, operationally, remain to be seen. However, she has said in previous debates that her appointee for the Managing Director’s office would have a directed focus on those efforts.

Public health and safety

Throughout the development of the mayoral race, candidates have made public safety their foremost priority and could often be seen touting records at different events to lay out policy platforms.

In Parker’s case, it came in the form of 300 uniformed officers, following a Neighborhood Safety and Community Policing plan introduced in 2022, after the city continued to recover from 562 homicides in 2021.

Parker believes in the power of policing “with zero tolerance for any misuse and abuse of authority,” she said. “Some people think it's heavy-handed,” Parker added, referring to calling a state of emergency.

And similarly to Allan Domb, she seeks to engage the state to intervene, although details remain undefined. What did remain clear is that Parker would invest in community policing to continue her previous measures in City Hall to “ensure that we have proactive, community policing” and address crime through what she called the three buckets: prevention, intervention, and enforcement.

There are mixed feelings about policing in Kensington, where patrols are observed just off the Kensington-Allegheny subway stop, adjacent to neighboring open-air drug markets.

In December, Mayor Jim Kenney’s office released an end-of-year report of the city’s response to gun violence trends, highlighting strategies like operation pin-point, which takes a “surgical” approach by exploring the underlying conditions that breed gun violence.

The purpose was to have enhanced police officer presence and enforcement, similar to what Parker wants to do.

“I want community policing as well,” Parker underlined. “No one will tell me that I don't have a right to have both. I want my son to be safe. I want him to be safe, live in and walk in and enjoy this Philadelphia life.”

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.every voice-every vote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

LEAVE A COMMENT: