Curfew in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro

"If the government doesn't have the capacity to handle this, organized crime will," the message circulates in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

Slowly, Latin American countries have been turning off the lights and quarantining themselves as an unpleasant and painful, but necessary, mechanism to contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, three countries have been particularly reluctant to take the radical measures needed to contain the advance of the virus: Mexico, Brazil and Chile. The argument of all three has been the same, to protect the economy. But the only way to contain the pandemic is to hurt the economy. By doing so, you accelerate the possibility that countries will focus on rebuilding it.

In the case of Chile, at least, quarantine has already been decreed in part of the capital, Santiago, but it will only last seven days. Considering that the incubation period of COVID-19 is 14 days on average, a quarantine this short ends up being a salute to the flag. However, just the fact of decreasing the interaction between people already decreases the number of possible infections, which represents some degree of progress.

In the case of Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador continues to underestimate the seriousness of the epidemic in his country and insists that there is no reason for its citizens to quarantine. According to an epidemiologist consulted by the New York Times, all the conditions are met for the coronavirus outbreak in Mexico to be as serious or more so than in Italy.

Brazil reported the first case of COVID-19 on the continent, currently reporting 3,477 confirmed cases and 93 deaths and despite this, Jair Bolsonaro, the president, has dismissed the scientists' recommendations regarding the coronavirus just as he has in the past regarding climate change.

In his statements he has not only underestimated the seriousness of COVID-19 - which he has described as a simple flu - but has also undermined the quarantine measures or curfews imposed by governors in the different regions of Brazil.

He even went so far as to call on his supporters to take to the streets on March 15 to protest against the Supreme Court of Justice and call for the closure of Congress. This action, in addition to endangering the health of thousands of attendees and their social circle, has been seen by several critics of the Brazilian president as a just cause for impeachment. There are already at least three formal requests for it to happen.

One of the clearest and most controversial expressions of how Bolsonaro has prioritized the economy over health care has been the publication of the video "Brasil nao pode parar" (Brazil cannot stop).In it, you can see images of workers from different economic sectors and the idea is repeated again and again that for the well-being of the population, and even for those affected by the COVID-19, it is essential that the Brazilian economy continues to move and that, therefore, it is necessary to go out and work.

The voices of opposition to Bolsonaro have made themselves felt not only in the government and opposition sectors, but also in the civilian population, which has made itself felt through pots and pans from the confines of their homes and, more surprisingly, from organized crime.

RELATED CONTENT

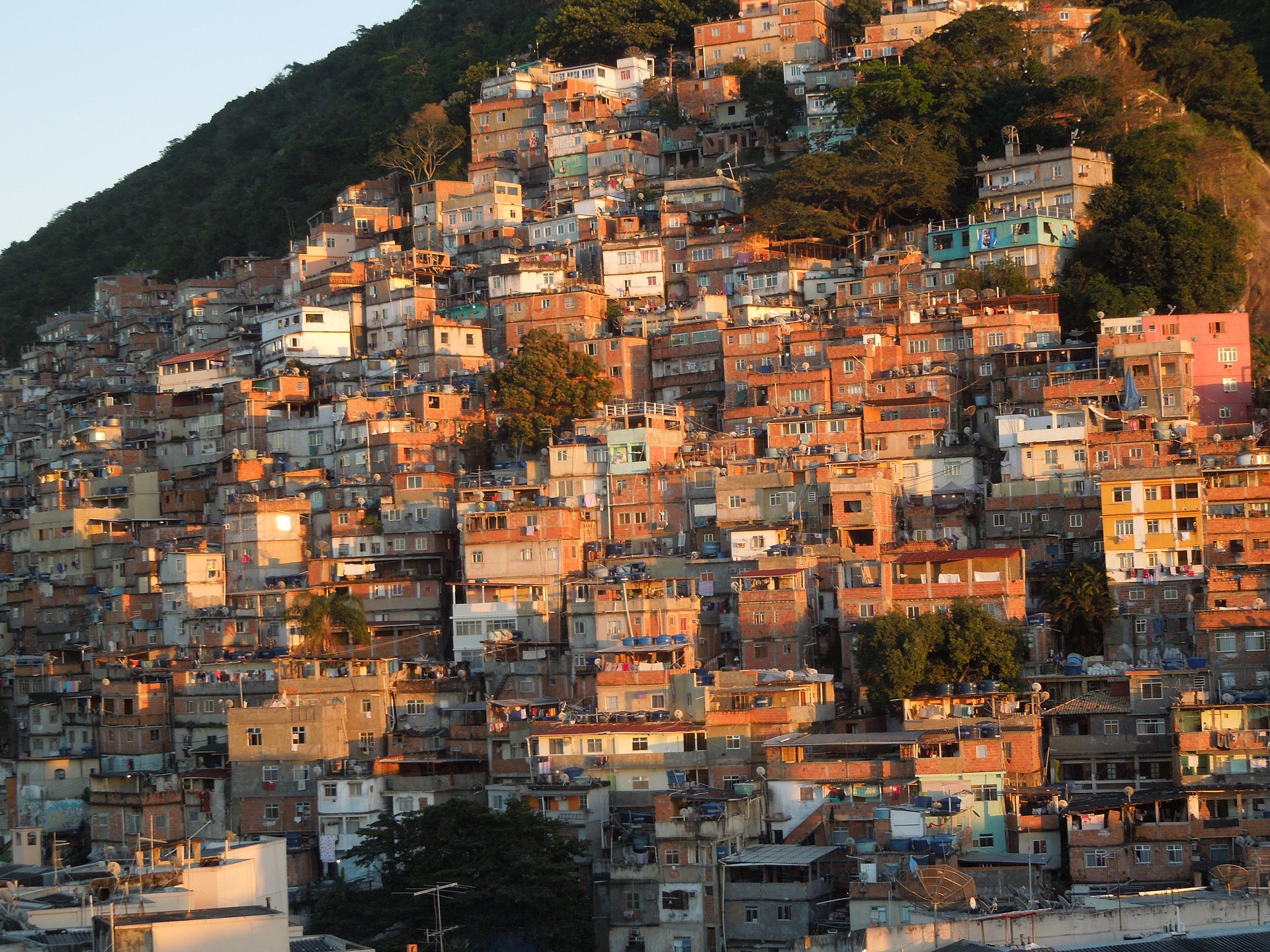

Through text messages and social media, the milicianos imposed a curfew on the favelas of Rio de Janeiro starting at 8 p.m. on March 22.

"We want what's best for the population. If the government doesn't have the capacity to handle this, organized crime will," the message said.

As in many other areas of Latin America, Africa and Asia, especially, in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, sanitary conditions make the most basic infection prevention measures difficult: how can you ask people to wash their hands every three hours if all the water they have has to be used exclusively for drinking?

The economy is in tension with the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic through a two-pronged approach: on the one hand, the social distancing that is indispensable to avoid contagion slows down the economy and breaks multiple links in the productive chain.

This, in turn, weakens the middle class and impoverishes the lower classes, forcing them to take to the streets, because in the face of hunger there is no quarantine or valid curfew.

The fact that the milicianos went out to impose a health measure that the presidency has refused to adopt shows a power vacuum that contributes to further aggravate the situation in Brazil. At this moment the country is a time bomb, where is it going to explode?

LEAVE A COMMENT: