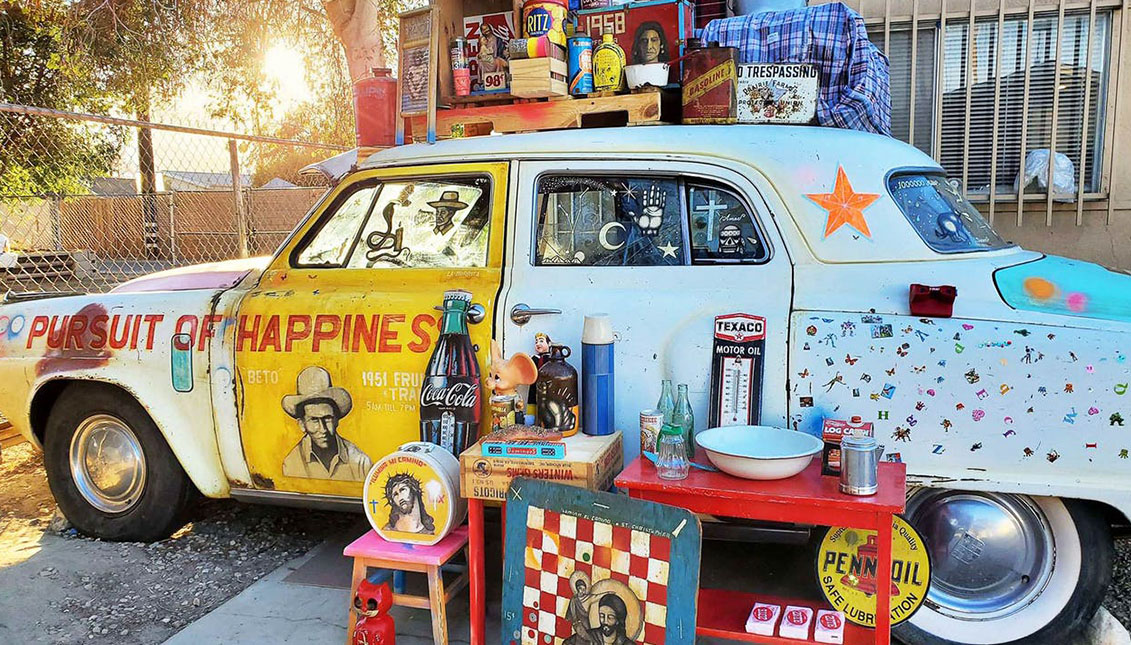

'Pursuit of Happiness,' Art on wheels to tell the difficult journey of Latino farm workers in the U.S.

On Dallas' Main Street, a 1951 Studebaker "roars" reminding us that there is still reckoning with the past.

In the Jim Crow era, when discrimination against non-whites —mostly African Americans — was legal and applauded, racialized people used the now-famous travel guide, The Negro Motorist Green Book, to find out where they could sleep; which restaurants would let them in, and which towns they should not cross after sundown at the risk of their lives.

Latino farmworkers crossing from one state to another to harvest crops faced much the same fate, but they had no travel guide like the Green Book. They had to rely on the warnings of their community members and luck.

The parents of Mexican American artist Carlos Ramirez were born in Mexico. As a young couple searching for a dream, they traveled all the way across the United States, from Texas to California, to work during the harvest season.

Carlos and his two older sisters traveled with them in a 1951 Studebaker, its engine roaring down the road as they tried to guess in which town they would find friendly foremen and locals, and in which town they would be kicked around for being migrants.

"They never stopped in hotels because they didn't know if people would be hostile," Ramirez told Texas Monthly, "They went through word of mouth: other migrants who shared locations or places that were safe."

Until 14 February, the odyssey experienced by Carlos' parents and many other migrant day laborers has its motorized tribute at Altar to a Dream, an installation in the form of a 1951 Studebaker in the heart of downtown Dallas, along the iconic Main Street.

The car is a reproduction of the one his parents used, but Ramírez has also added other symbolic decorations, such as small altars of Mexican and Chicano tradition and religious icons made from art found on the streets.

Like a box of apricots from Sacramento turned into a table, a metal lunch box with the image of Christ and the phrase "light my way" or a checkerboard decorated with the patron saint of travelers, San Cristóbal.

"My mother used to tell me that crossing the United States in mid-century America was like crossing a chessboard, that you never knew when you were going to land in a friendly place or an unfriendly place," the artist told Texas Monthly.

Many of the objects included in Altar to a Dream tell pieces of a story, the one Carlos Ramírez heard from his parents about the difficult life of farm laborers and the peasant struggles of the 1960s - his mother was a member of the United Farm Workers Union led by César Chávez. There is also a reminder in the back of the car in the form of stickers and fantasy constellations to the children who work in the fields.

RELATED CONTENT

"I remember (as a child) riding in the back seat, looking out the window and letting my imagination run wild," Ramirez said.

Altar to a Dream is part of the PBS American Portrait initiative, a multimedia project that includes public art exhibits, docuseries and multimedia events, such as the Tulsa mobile art exhibit by Rick Lowe to engage neighbors in the history of the tragically famous 1921 racial massacre.

"The pursuit of happiness applies to everyone."

The work's location in Dallas is not random, as the city is closely linked to the civil rights struggle and the Kennedy assassination.

Moreover, Altar to a Dream is very nearby another emblematic installation, Tony Tasset's Eye, which was graffitied during the BLM protests and which has become one of the places that will go down in the history of the struggle against supremacism in the United States.

The side of the 1951 Studebaker reads "Pursuit of Happiness", which is particularly important to its author:

"I think there's still a reckoning, or there's still a lot of healing to be done," Ramirez says.

"I thought that phrase fit perfectly, just to illustrate what it was like for so many different people - regardless of their background, color, or anything else - to establish their legacies, and how America was shaped by them as well. I thought: The pursuit of happiness applies to everyone," he concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: