The Brown Church: Christian activism for the "communion" of U.S. Latinos

From Friar Antonio de Montesinos, who preached against the Spanish conquest, to Cesar Chavez's struggle for farm worker rights, faith and justice have long…

Religion has had an unmatched historical weight within human societies, and still does to this day. For example, heading into the 2020 election and in its aftermath, a lot has been written about the growing power of the Latino evangelical community as a swing vote that could tip the balance of an election. A number of analyses have also been published about the political tendencies of Latino Catholics, who still make up 47% of the entire Hispanic population in the U.S.

However, beyond political campaign issues, the Church has been at the forefront of the struggle for civil rights in the United States and in its creating its structure.

As Robert Chao Romero, author of Brown Church, says, in reviewing 500 years of history, social justice, heritage and Christianity have gone hand in hand. However, he also acknowledges that many young university students feel lost in trying to reconcile their faith with their activism today.

That's why Chao, of Asian-American descent and professor of Chicano studies at UCLA, decided to write Brown Church, in an attempt to explain to young people that "they feel on the spiritual frontier." Christianity, like Latinidad, is not monolithic, and there is another story never told about the Latino believers that brought change to Latin America and the United States.

"We care about justice. We care about our communities. We want to dedicate our lives to those issues, but we also want to capture the fullness of our cultural background. Yes, we have Spanish ancestry, but we also have indigenous ancestry," the scholar said. "We're not just going to assimilate."

RELATED CONTENT

In the book, Chao Romero recalls 1511, when the Dominican Friar Antonio de Montesinos preached his hard-hitting sermon condemning the Spanish conquest in a thatched church on the last Sunday before Christmas. Another priest posed a similar challenge in the mid-1850s, challenging South American oppression in the American Southwest.

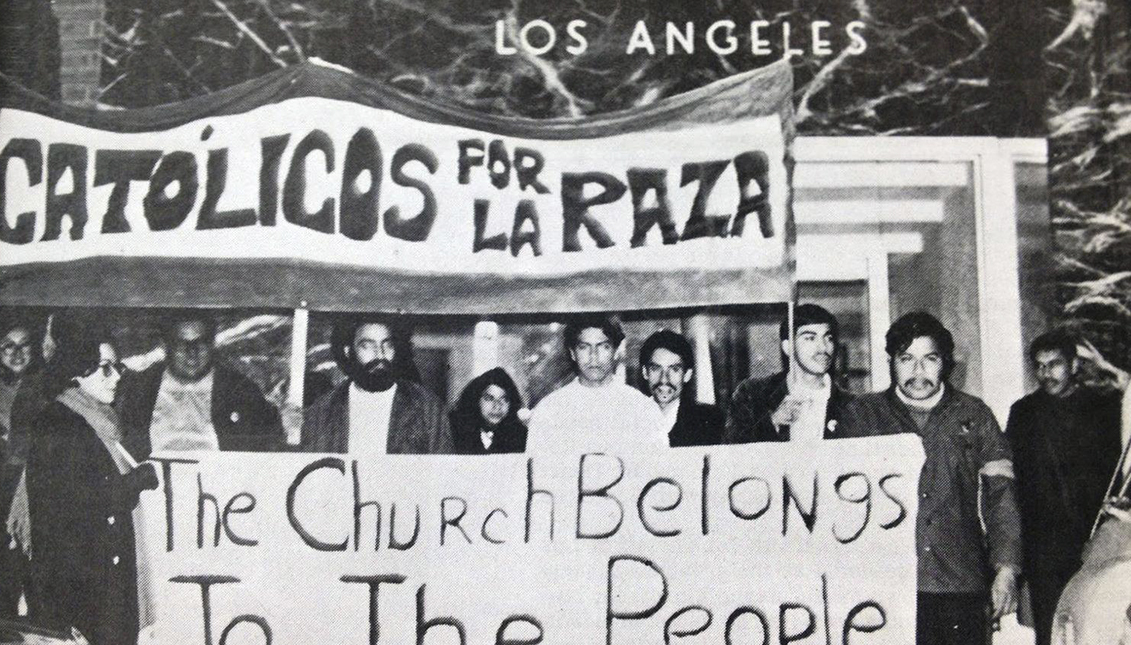

Cesar Chavez did the same when he fused religious symbols and practices such as fasting, pilgrimage, and the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe with Catholic with social teaching while leading the struggle of farm workers for more rights. The sanctuary movement of the 80s also united synagogues and churches to give refuge to migrants fleeing violence in Central America.

If Jesus, says Chao, was on the side of the oppressed and was the "Savior of Galilee," his ideas are the opposite of segregation. Therefore, "we need a social identity that captures our hearts for justice and the fullness of our cultural background," he concludes.

The brown theology the book boasts about extends from the Latino to the universal, trying to build bridges between those who embrace the faith to expand an urgent cultural, historical and spiritual interpretation that is no longer on the fringes.

Because the Brown Church, says Chao, is the 'Church of All.'

LEAVE A COMMENT: