The Black Messiah who decolonized Christian supremacist merchandising

During the civil rights movement, a Detroit reverend proclaimed, "Jesus is black" and released the prayers of whiteness.

Half a million Latino soldiers, 1.2 million African Americans and 25,000 Native Americans served in the military during World War II. When not dodging enemy fire, Christians prayed for their safe return home using prayer cards distributed by the Salvation Army and the YMCA through the USO.

These millions of cards, produced in bulk, were distributed not only to soldiers but around the world as part of the "Christ in Every Pulse" project, which was promoted by then President Dwight Eisenhower and the Trump family's pastor, Norman Vincent Peale.

Now back to the battlefield: imagine again those soldiers who gave their lives for a homeland that segregated them and who entrusted themselves to a white, blond Christ, someone who in no way resembled them - or anyone born in what is now the Middle East.

A religious image that embodied a global God and that, long before the rise of BLM and the demolition of Confederate statues, was to be at the center of a revolution for racial justice. It happened in the 1960s — it could not have been otherwise.

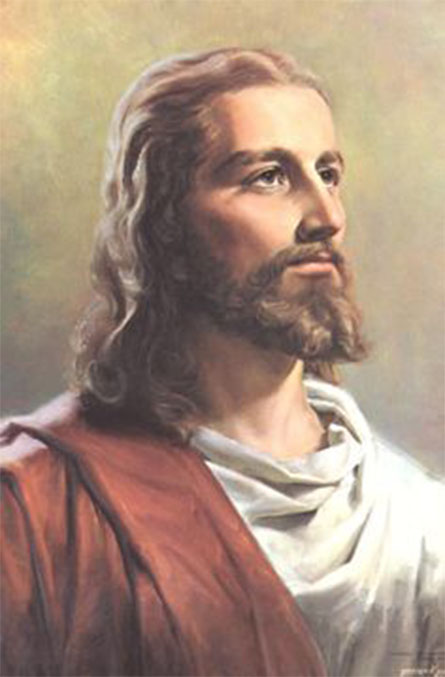

They must have seen it reproduced a billion times and it came to define the look of the central figure of Christianity, with his gentle blue eyes set in the sky and his pale, elongated face. It is The Head of Christ by Warner E. Sallman, a Chicago commercial artist and religious illustrator who first painted the image in 1924 as a charcoal sketch for the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant's youth magazine The Covenant Companion in 1924.

With it Sallman intended to convey "a very similar feel to the image of a school or professional photograph of the time, making it more accessible and familiar to the public," Tai Lipan, the director of the Indiana Anderson University gallery that has housed the Warner Sallman collection since the 1980s, told Broadview.

The image became so popular that not only was the artist commissioned to create a painting based on his drawing, but Sallman sold the original to a religious publisher, Kriebel and Bates, and it began to be printed on prayer cards circulated in Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical churches, Black and white. It then went on to produce all kinds of merchandising, such as clocks, pencils, bookmarks....

At some point it became the "true" face of Jesus, eclipsing those other images that had existed up to that point in which people had depicted Christ as a member of their ethnic group or culture.

However, many people, especially minorities, saw it as neither logical nor realistic to have to pray to this Caucasian son of God and globalization, who would eventually be called "the best-known American work of art of the 20th century."

BLM activists were not the first to criticize this Nordic Christ as an example of white supremacy. During the civil rights movement, pastors and activists reacted angrily to an image they refused to enshrine.

Among them was Malcolm X, who blasted Christianity as a "white man's religion" and addressed his congregation from the pulpit, telling them that "the white man has brainwashed us Blacks into looking at a blond-haired, blue-eyed Jesus! We are worshipping a Jesus who doesn't even look like us!.... The white man has taught us to shout and sing and pray till we die, to wait till we die, for some dreamy heaven in the hereafter, when we're dead, while this white man has his milk and honey in the streets paved with gold dollars right here on this earth."

RELATED CONTENT

Around the same time and founded by James H. Cone in 1966, black liberation theology encouraged African-American churchgoers to love their own Blackness in a country of endemic racism as it attempted to reconcile Christianity and black power, the non-violence of Martin Luther King Jr. and the belligerence of Malcolm X.

If Christ, they said, came to free us from our oppression, he had to be someone in our image. And they began to progressively decolonize their religious spaces, including images of the European Jesus.

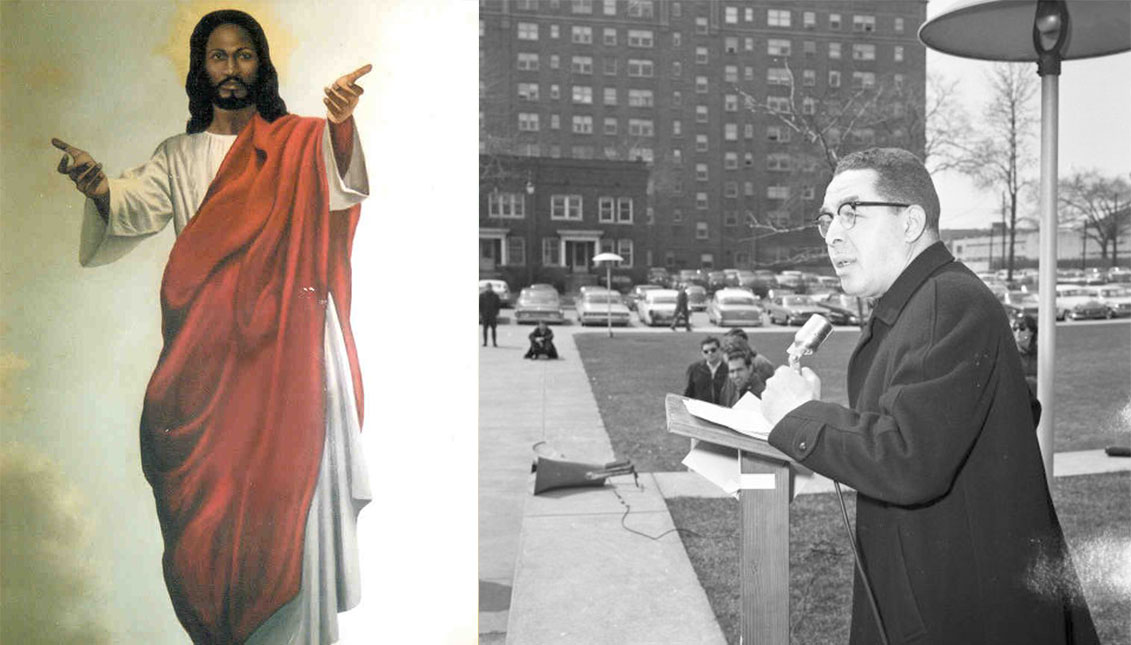

Reverend B. Cleage Jr, a pioneer in proclaiming from his church in Detroit that Jesus was as black as his followers, lived much of his youth with the contradiction of being too light-skinned. His father had been a prominent physician in Detroit - he was designated "city physician" by the mayor in 1930.

A graduate in sociology, theology and film studies — he wanted to make religious films, but eventually gave up — Cleage pastored churches in Kentucky, San Francisco and Springfield, Massachusetts, until he returned to Detroit in 1951 to serve at St. Mark's Community Church mission. But several white church leaders objected to the way he led his black congregation, and he left with his congregants to found what would eventually become the Central United Church of Christ, with a strong focus on political leadership and outreach to the poor.

While Cleage initially sided with Reverend King and his idea of non-violence and integration, he was a harsh critic of white participation in the 1963 March for Freedom in Detroit and became increasingly sympathetic to Malcolm X's Black nationalism, eventually running for governor of Michigan and becoming editor of a weekly newspaper that circulated in the city's African-American neighborhoods.

"The white man has brainwashed us blacks into looking at a blond-haired, blue-eyed Jesus!," claimed Malcolm X.

But it was not until 1967 that he came to prominence for his radical reinterpretation of Jesus' teachings, starting the National Black Christian Movement and installing a painting of a Black Madonna holding the baby Jesus in his church, which he renamed again three years later as the Pan-African Orthodox Christian Church.

Convinced that the community should know its African history, more identical shrines sprang up in Kalamazoo, Atlanta and Houston, and Cleage also changed his name to Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman — Swahili for 'liberator.' His mission was as much to help the economic and educational advancement of the faithful as it was to rewrite the Bible as a truly sacred book for African-Americans. And, above all, the figure of Christ.

When Cleage published The Black Messiah in 1968, what Cleage did was to present Jesus as a kind of Malcolm X of his time, a black revolutionary leader who was to save his children, for under his guidance and protection they could solve all the political and economic problems that beset them.

Today, in the light of the new times, the image of these Black Jesuses present in Detroit and other cities hold up a mirror to a community whose referents do not resist being whitewashed. Artists have also emerged, new religious recreations adjusted to the ethnic particularities of their followers and even a sitcom that premiered in 2014.

Every people has the right to its own mirror of divinity and colonizing spirituality is one of the reactionary forms of subjugation and violence. Amen.

LEAVE A COMMENT: