‘Displacement isn’t an option’: Philly fights for mixed-income housing

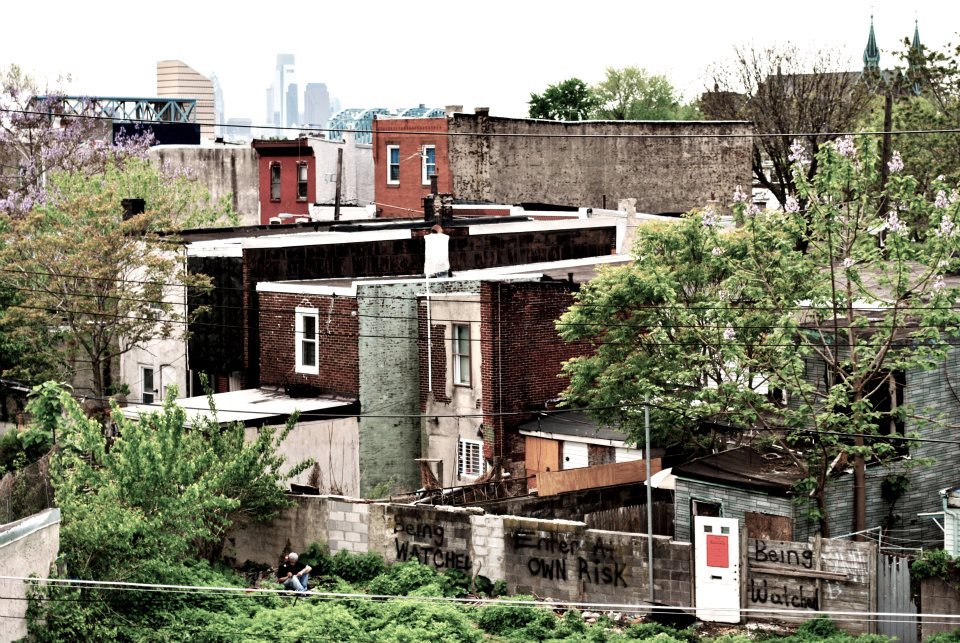

Mixed-income housing. It’s been called “the lynchpin for social justice.” It’s brought up in every discussion about gentrification, and Philadelphia is far from the exception. So how do we fare when it comes to commingling residents with different incomes?

In its new platform agenda, the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations (PACDC), which represents some 100 CDCs, has requested the city create a long-term strategy towards integrated mixed-income housing.

Each year, the Office of Housing and Community Development (OHCD) drafts a “Consolidated Plan,” a.k.a. Con Plan, that addresses how to spend federal money on housing development. But PACDC criticizes the plan’s lack of forward thinking. In their new agenda, they say the plan doesn’t foster an environment for market-rate homes in disinvested areas, nor does it encourage stability in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. More urgently, the Con Plan has no blueprint for integrating subsidized homes alongside market-rate home developments “in ways that create truly mixed-income neighborhoods.”

Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) was one of the CDCs to call on the next mayor and the City Council to address the impacts of displacement in its base community.

“The fact is there’s a lot we don’t know about displacement and mixed income neighborhoods,” said John Chin, executive director of PCDC. “Policy makers really need to collect better data on what’s happening with low-income folks who are forced out of their neighborhoods.”

PCDC formed almost 50 years ago to combat displacement brought on by urban renewal projects like the Vine Street Expressway, casinos, and federal prisons. They developed one of the first successful models of mixed income housing in Philly, which is still functioning.

Today, displacement in Chinatown is the story of rising housing and property costs, Chin said, and they’re still fighting. Recently, they have built 24 commercial units and more than 226 units of mixed-income housing. They’re also in partnership with Project H.O.M.E to build a new 94-unit low-income community which will house low-income families, formerly homeless persons, and at-risk youth.

“Chinatown needs mixed-income residents to be successful and to continue to grow. We can’t survive on a solely low-income community, but at the same time displacement isn’t an option,” Chin said. “What we’re saying is we want to find a way to welcome middle- and higher-income to be a part of the community, while still enabling our low-income families to stay and enjoy the fruits of the change.”

The city already has the LOOP program and the property tax deferral program in place, but PACDC has been reportedly working on a collaborative study about displacement that may be the basis for new legislation. We can’t say what the figures are yet, but we can say they’re eye-opening, and that displacement is alive and well in Philadelphia’s gentrifying communities.

Ultimately, Chin thinks we should be looking at this challenges through the best practices and models. Creating mixed-income housing can feel like an idealist’s pursuit. Can one community represent the full range of a city’s income? Should it? Outside of Chinatown, Philadelphia has successfully brought together low- and moderate-income families, and moderate- and upper-income families, but rarely both ends of the spectrum.

Maria Gonzales, president of Hace, works with very low-income families in the Fairhill neighborhood. Hace was able to secure funding for 50 new construction units for low-income homeowners, and they asked funders to set aside an additional ten units for higher income families (80 percent and above). Gonzales’ vision is a common and noble one: to make sure everyone benefits from the development.

“We’re trying to create new and affordable housing for everyone,” she said. “We don’t want to have too much of one.”

But Fairhill still hasn’t seen the wave of investment interest that nearby neighborhoods like Northern Liberties and Fishtown have. Hace’s develoments are almost exclusively owned by low-income families at the moment. Then again, maybe that’s inevitably what keeps it affordable. Each unit is being sold for $90,000, and Hace received subsidies to help low-income buyers with $5,400 for a settlement and closing assistance. All a potential owner needs to put down is $1,500 for a brand new, high energy-efficient home. In short, the threat of high-income earners supplanting the neighborhood “isn’t a threat yet.”

“We’re not there yet,” Gonzales explained. “We’re on the opposite side of the spectrum. If you own your property, and ten or fifteen years from now you see the wave of gentrification, at least we have a higher percentage of people who own their home. If you own your home, you’re not going to be displaced.”

Consider the type of families that can afford a $1500 down payment on a home versus those that could manage a $20,000 down payment.

“Awesome Town,” Fishtown’s mixed-income experiment, has a distinctly different feel. Four years ago, North Kensington CDC collaborated with Postgreen Homes in an effort to preserve affordable housing for people in the neighborhood. They finally got a subsidized plot of land from the city, and 14 houses were built. Ten of those houses are to be sold at market rate, which is a staggering $400,000 to $450,000 — “Which is absolutely insane, I know,” said an NKCDC representative — and the other four are being subsidized by those ten houses for $200,000, “which isn’t as low as we would have liked, but without doing any other subsidy, it was the best we could do.”

NKCDC and Postgreen were able to keep four “moderate income” households in the neighborhood, but the story of Awesome Town, if anything, shows us how quickly a gentrifying neighborhood can unintentionally shut out an entire class of the city.

PACDC intends to release its study in the coming week. This is a developing story.

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.