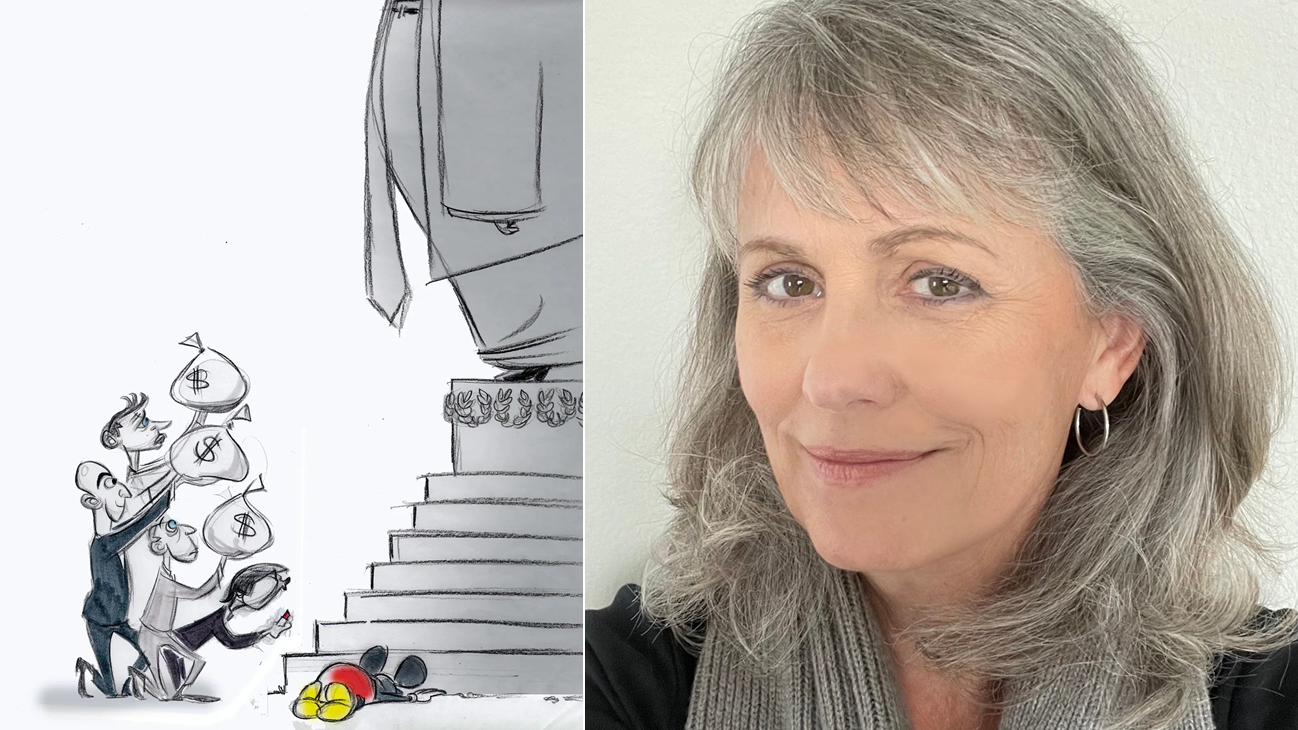

Kimberly Teehee wants her spot in the House, and for the U.S. to honor its 187-year-old treaty with her tribe

Pending a House hearing later this month, the Cherokee Nation leader could be the first Native American delegate to Congress.

Kimberly Teehee’s career in politics is one to envy.

Ever since entering the field in the 1980s after graduating from law school at the University of Iowa, the Cherokee Nation powerhouse has risen to heights rarely seen by a Native American woman in U.S. government.

In the 90s, she was the Democratic National Committee’s first deputy director of Native American Outreach and then served in a similar role as part of President Bill Clinton’s second inauguration committee. Following the DNC and Clinton transition team, Teehee would then go on to serve as a senior advisor under longtime Democratic Congressman from Michigan Dale Kildee, who served as co-chair of the Native American Caucus in the House.

A year into President Barack Obama’s administration in 2009, Teehee would serve on the White House Domestic Policy Council, advising the president on Indian County issues as the senior policy advisor for Native American Affairs.

But in 2019, Teehee was nominated for a position that no Native American — man or woman — had ever held in U.S. history. She was put forth as a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives on behalf of the Cherokee Nation.

The position is one that is 187 years in the making, dating back to the Treaty of New Echota.

Signed by the U.S. Government and Eastern Cherokee Nation of Georgia in 1835, the treaty initiated the Trail of Tears, which saw some 16,000 Cherokee Nation members and their slaves march West to Oklahoma from their ancestral homes in the East and U.S. South. It is estimated that more than 4,000 Cherokee and an unknown amount of slaves died over the course of the three-year migration, between 1836 and 1839.

In addition to ceding its tribal lands to make the brutal trip West, the tribe was guaranteed a non-voting seat in the House of Representatives.

In the role, the delegate would act in the same manner as other non-voting delegates from other U.S. territories like American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the District of Columbia, and the Northern Mariana Islands, and be able to take part in committees and vote on bills as part of them, but are unable to vote on bills posed to the entire House.

Up until 2019, Congress had failed to follow through with the delegate portion of the almost two-century-old treaty.

That is, until Cherokee Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. nominated Teehee to be the Cherokee Nation’s delegate in 2019.

RELATED CONTENT

“It would be [a] small measure of justice for those who lost their lives on a forced march,” Teehee said in a recent interview with Kentucky outlet, The Sentinel Echo.

She was poised to make history that year or in early 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic hit, pushing back the approval by the House. 2021 then became the target year, especially with Teehee advising President Joe Biden to say he would push for more representation for tribes on the campaign trail. But 2021 came and went.

With the end of 2022 looming, the Cherokee Nation reinforced its desire to get Teehee confirmed via a House vote. It even opened a form for Americans to call on their representatives to push for action.

In preparation for the decision, the Congressional Research Service put together a report (released in July) detailing a modern interpretation of the 1835 Treaty to guide decision making. There are also concerns about giving members of the Cherokee Nation dual representation in the House.

“There’s a lot of people that will say: ‘Well, that delegate’s chosen by a council, not by a general election,’” Oklahoma Rep. Tom Cole was quoted as saying by the New York Times earlier this year about the delegate effort. “And Cherokees then get two votes: your vote for a council member and their vote for the congressman of their own district, so they sort of get to two bites of the apple.”

However, the Congressional Research Service report recommended that in the event of “ambiguities regarding tribal interest,” they “must be construed to the tribes’ benefit.” In other words, tribes should get what they want in the event of dated language in the treaty getting in the way.

On that front, Teehee and the Cherokee Nation could be opening up the door for more tribes across the country to get more of a say in Congress.

In addition to the Treaty of New Echota granting a delegate to the Cherokee Nation, the Choctaw Nation could also be eligible for a delegate under the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. An even earlier treaty from 1778 with the Delaware Nation could also grant it a delegate.

Amid a time with a Supreme Court that is slowly stripping away the sovereignty of Native tribes, delegates like Teehee could stand on the front line and in as important a place as ever.

LEAVE A COMMENT: