One year after Hurricane Maria: The long road to recovery

As the nation is finally coming to grips with the true statistics that define the widespread devastation caused by Hurricane Maria a year ago, those who were…

In any wide-scale disaster, there are things that remain unclear long after the physical dust settles, and the rain and winds abate. In the act of picking up the pieces we begin to puzzle out some of the sources of the damage — the faulty construction and already-broken scaffolding that facilitated the tragic collapse, however natural the initial cause.

For the 3.8 million Puerto Ricans whose lives were changed by Hurricane Maria, the dust has still not settled. The full picture of what happened a year ago when the Category 4 storm slammed the island, and the aftermath of the worst natural disaster to strike the region in nearly a century, is still blurred by incompetency and willful ignorance.

The revised official death count by the government of Puerto Rico, discovered by a team of researchers from George Washington University commissioned by the island’s authorities, was just announced on Aug. 29. It was found to be (and has now been officially raised to) 2,975 — more than 46 times higher than the official death toll of 64 which the government of Puerto Rico and the U.S. federal government had stood by for nearly a year after the disaster. An independent Harvard study, released several months earlier, estimated that number to be even higher, at 4,645.

Now there are finally officially recognized numbers to begin to outline the catastrophic destruction that President Donald Trump, upon visiting the island in the weeks following the disaster, dismissed with a toss of paper towel rolls into a crowd and assertions that FEMA had done “an amazing job,” that Maria was not a “real catastrophe” like Hurricane Katrina— a strategy of avoidance that he has continued to use even after the most recent death toll announcement, which he failed to recognize in another press conference Aug. 29.

"The administration killed the Puerto Ricans with neglect. The Trump administration led us to believe they were helping when they weren't up to par, and they didn't allow other countries to help us,” San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz, who has become an iconic figure of dissent, told CNN following the president’s comments. “Shame on President Trump for not even once, not even yesterday, just saying, 'Look, I grieve with the people of Puerto Rico.'"

As with so much of the Trump administration’s actions, he has, in effect, expressed more grotesquely an attitude the United States has continuously reinforced: a disregard of the island and typical colonialist treatment. One of the most telling examples is the Jones Act — a piece of legislation dating from 1920 that prohibits any non-American ships or cargo from entering the island’s ports, and has continuously made the inflow of goods to the island more expensive. It proved fatal after Maria as Puerto Rico was unable to receive desperately needed supplies and aid sent from other countries in the disaster’s immediate aftermath.

Above all, the self-admitted failure of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to adequately prepare for and respond to Hurricane Maria is a glaring piece of the puzzle — regardless of the fact that the agency has, since the disaster, funneled $2.6 billion in aid to Puerto Rico, and that their response to Maria represents the longest continued food and water relief mission in the agency’s history. In an internal report made public on July 12, FEMA acknowledged that it was unprepared for a storm like Hurricane Maria in the region, as 90 percent of the emergency supplies stored on the island had been depleted after being shipped to the U.S. Virgin Islands following Hurricane Irma on Sept. 7. The agency then ran into multiple issues in carrying out relief efforts on the ground due to limited communication means and lack of knowledge about the island’s infrastructure.

There are explanations and blame to go around in the before, the during, and the after for the tragedy. But for the more than 2,000 Puerto Rican families who moved to Pennsylvania after the storm — the second-highest number of evacuees from Maria in any state other than Florida — the after is still ongoing, and presents a difficult and still unplotted road ahead.

Few know better the depths of damage done by Maria and the fight to survive both on and off the island than Charito Morales. Activist, community organizer at Providence Center, Puerto Rican and all-around “warrior,” as a family member described her, Morales is also a nurse, and was among the first responders on the island after the hurricane hit, joining a search and rescue team that flew out from Philadelphia on Sept. 21. There, she focused on healthcare and helped set up ambulatory clinics to reach those most in need.

Soon after returning on Dec. 20, Morales realized that there was also a huge unmet need in the city for some of the estimated 900 families who had been displaced by Maria and began seeking shelter and looking to build a new life in the greater Philadelphia area.

As the first Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Transitional Housing Assistance (TSA) deadline of Feb. 13 drew closer, Morales and other community leaders mobilized and held a protest on Feb. 12 at City Hall calling for an extension, and greater support of evacuee families’ needs.

The same group of activists also opened up library space and the Providence Center to families in the area that had been displaced, creating a spreadsheet to register names and contact information. They aided many families who didn’t qualify for FEMA’s TSA program or had difficulty with the process and providing accurate records due to the blackout situation back on the island. The community space at Providence Center also became a central place to gather mattresses, furniture, food and other donations.

But Morales realized that there was another overlooked piece of the recovery process.

“I understand the parents were really frustrated because they needed the services... [But] nobody thought about the youth,” said Morales, noting that the young people were coping with huge changes while navigating a different language and culture.

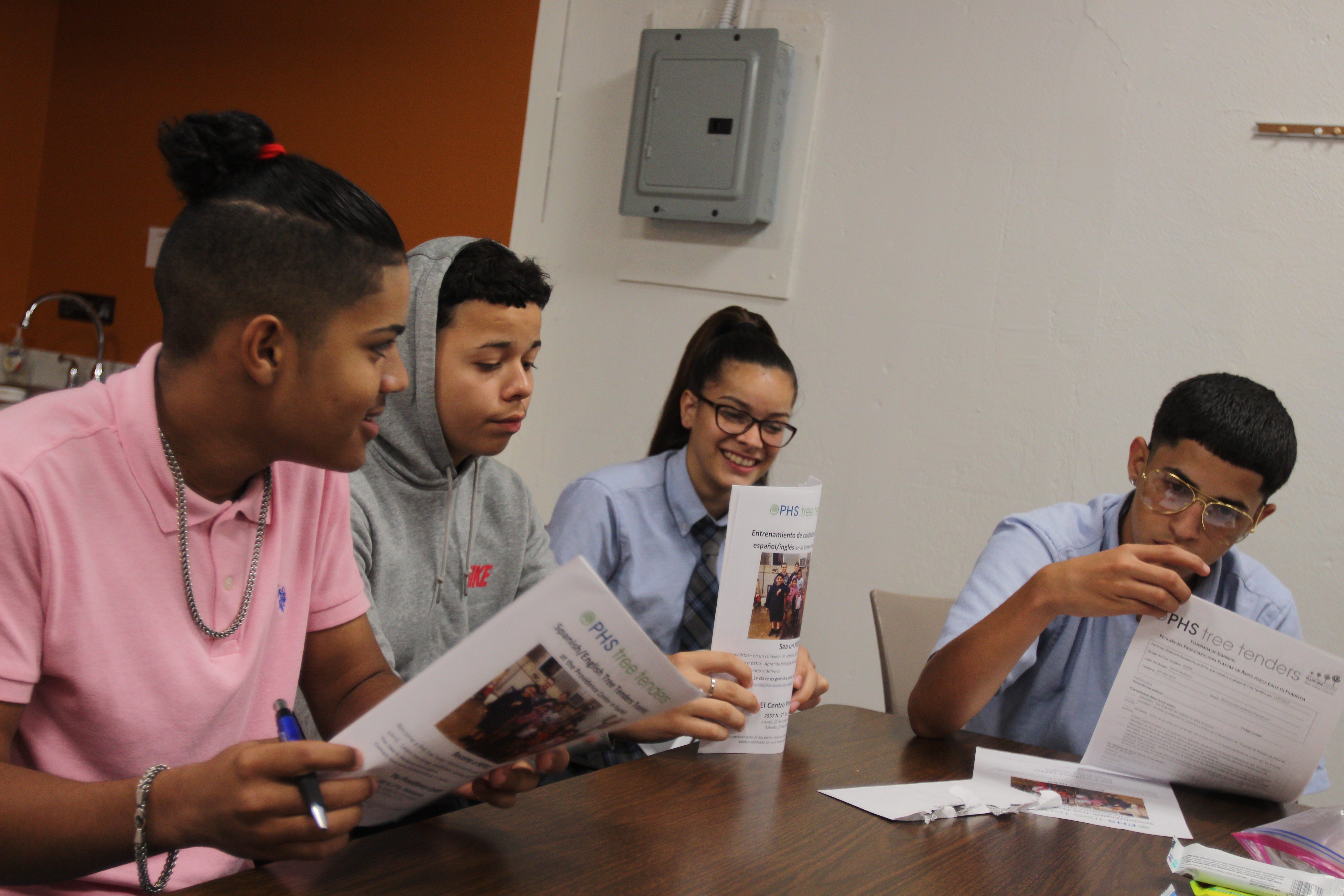

So Morales took action, establishing a regular group of 48 students, the majority of them from displaced families from Puerto Rico, which allowed them to connect with one another and, as Morales put it, “take ownership of the community that they are living now” by engaging in projects such as community gardening, mural painting, and more.

On a rainy Friday afternoon in late August, the group discussed an upcoming project with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society in which members will plant trees in Fairhill. The room was noisy - a little loud, as Morales said she likes to warn those who come to visit, but also admittedly relishes as a sign of the comfort kids feel when they walk in the door.

Chris Joel Morales, 18, said that though he and his sister, Judy Morales, 16, had met some other displaced families in the hotel where they stayed when they first arrived in Philadelphia, the Providence Center class helped them feel more at home.

Judy Morales agreed.

“It’s gone well for me. I’ve made friends...When I arrived here I didn’t have friends or anything,” she said.

The gathering at Providence Center in North Philadelphia resembled another meeting that took place on a mid-August afternoon in a church nestled amidst the rolling fields and slat-board and brick houses of Reading, PA.

RELATED CONTENT

“At some point, I thought I was going to die,” said Tamayríz López, 10, describing the storm’s devastation - the torn-off roofs, 50 days without water or electricity, the stories of neighbors in her hometown of San Sebastián who perished - which ultimately drove her and her family to move to Pennsylvania on Nov. 17, 2017.

But it wasn’t until that week in August, when López participated in the week-long Camp Noah program at St. Luke’s Lutheran Church in Reading, that she had been able to talk about her experience with peers who were also displaced by Maria.

The camp, which organizers hope to replicate in Philadelphia next summer, was an example of what Julia Menzo, co-chair of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), described as a necessary component in the “spiritual and emotional” recovery process.

[node:field_slideshow]

Menzo represents VOAD as a member of the Greater Philadelphia Long Term Recovery Committee (GPLTRC), a coalition of organizations which formed in March that seeks to bolster long term support of Maria evacuees.

The TSA deadline has once again been extended, this time to Sept. 14, but housing is still one of the most urgent of those needs. And though PA Gov. Tom Wolf’s recent visit to the island is a promising sign of future collaboration, there has yet to be a formal agreement between Puerto Rico Governor Ricardo Roselló and Wolf to establish Pennsylvania as an emergency state that would allow them to access federal funds for displaced Puerto Rican families living here now.

In the Philadelphia area at least, some TSA families and 30 other evacuee families were able to secure permanent housing through the Philadelphia Housing Authority designated “super preference” program for survivors of natural disaster.

Viviana Luis Hernández, whose three children participate in the program at the Providence Center, is among those who benefited from PHA’s super preference program, which enabled her to move into her own rented apartment on June 28. Hernández came to the mainland on Nov. 5 after enduring nearly two months living without electricity and running water near the Dam of Guajataca, which the hurricane almost destroyed.

For now, she and her family plan to stay in Philadelphia, since her children are getting good grades and learning English. Hernández’s viewpoint is in line with the vast majority of displaced Puerto Ricans in the state who, according to Menzo and Morales, are more inclined to establish a home here than the alternative: risking a return to an economy that was depressed even before the storm and contending with the continued instability of the island’s infrastructure and educational system.

Hope, for many Puerto Ricans on and off the island, has come not from the federal government, but from the faith in their own people — their joint resilience and their collective determination to forge ahead. Just in the pages of this publication, it has been clear to see how Puerto Ricans, from superstars to local heroes, have pitched in to bring to life the phrase many have rallied behind: “Puerto Rico se levanta,” or “Puerto Rico rises up.”

But Charito Morales warned that this catchphrase isn’t enough to ensure a true, sustainable recovery for the Puerto Ricans most in need. In her view, it can be used by government officials to obscure the fact that “everybody that really [needs it] doesn’t have any help yet.”

“Management needs to refresh. They need to get it together,” she added, explaining that medications are still in short supply, and education is less accessible after the government closed down 280 schools. The recovery process will be “long term,” Morales stressed, despite the fact that much aid has already dried up.

“People living without a roof, water, electricity. That’s not a third-world country. We’re American, we’re not second-class citizens,” she said. “But that’s how they treat us.”

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.