'I Look at the World,' showcasing the migrant and Black Lives Matter struggles amid a pandemic

Curated by longtime artistic director David Acosta, the new exhibit at the Da Vinci Art Alliance features two sets of work by Ada Trillo and Isaac Scott.

Other than exposing the flaws of the U.S. healthcare system, the COVID-19 pandemic also uncovered problems that plague different areas of American life, including race, politics, and immigration. They’re issues the country has been unable to fix, avoided, or purposely neglected.

As has happened before in history, when political leaders are unable to fix these problems and the media does not do its due diligence to correctly cover and bring awareness to them, art in all its forms is what is powerful enough to show the real nature of issues that millions hear about, but never see for themselves.

It’s for this purpose that photo exhibits like I Look at the World exist. The title is taken from a Langston Hughes poem, and was curated by Casa de Duende Artistic Director David Acosta. It’s a collaboration between three artists, and displays two sets of work from two Philadelphia-based photographers Isaac Scott and Ada Trillo that capture two sets of historic events that occurred amid the pandemic.

The same struggle for humanity

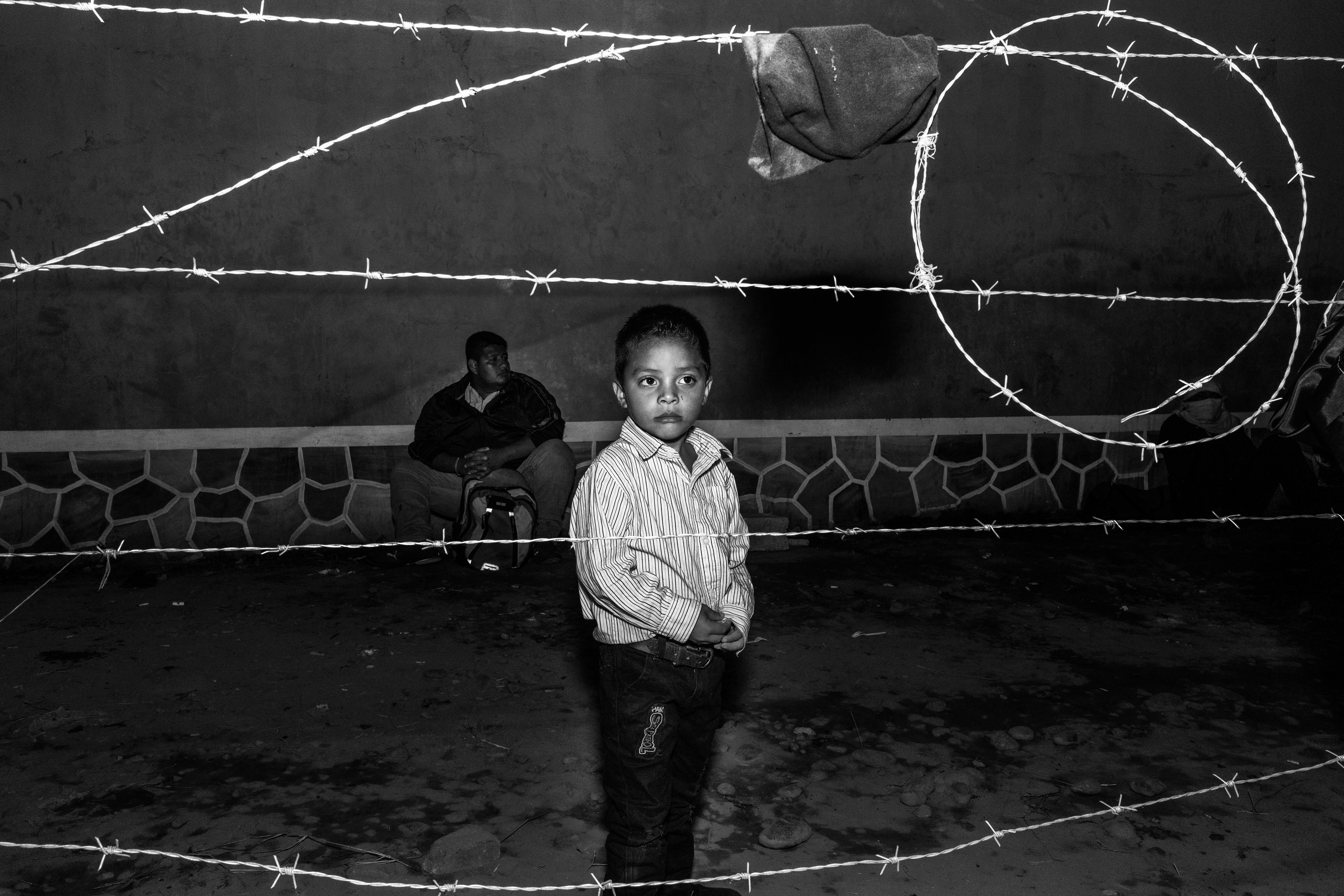

Scott captured the momentous Black Lives Matter Movement protests fueled by George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis Police and Trillo, the historic mass migrations of Central and Latin Americans to the U.S., as well as the famous “caravan” that carried migrants through Mexico to the southern U.S. border. The photographs, both forceful and compelling on their surface, tell both groups’ individual stories, but also depict the shared real life struggles for human rights, freedom, and greater opportunity.

Even as the photographs were taken by two photographers who come from different backgrounds, both are able to capture similar narratives through their camera lenses with their identities immersed into the work.

As Acosta said in his statement on the exhibit that sits on a wall left of the photographs: “This exhibition explores the complex role of the artist/photographer as both impartial observer, witness and participant, and the complexity, struggle, and acceptance of those complex roles at the intersection of art and subjectivity.”

Acosta, besides holding the Artistic Director position, is a longtime activist, artist, and cultural organizer. From early work in public health where he educated on HIV and prevention, to published literary work, to being co-founder of the Philadelphia Latin American Film Festival (PHLAFF), and a curator, he has overseen many art exhibitions over the years tackling the same issues I Look at the World does, but for different groups of people.

“Over the span of 10 years, I’ve done some that feature Latin American artists, exhibitions that feature LGBTQ artists, mixed exhibitions,” Acosta said.

At the center of those exhibits and I Look at the World, are also the artists.

“One of our goals is to really highlight the artists as an important commentator, as an important voice in looking at not only movements for social change but also the artists looking at the world. We’re interested in presenting artists as insightful critics to what they see and experience,” said Acosta. “In this exhibition it was important because I know that they were not only obviously artists photographing this, but because both of the artists come from the communities that are represented in the exhibition, I felt that they had a vested interest, both as participants as members of those communities, as witnesses, but then also as artists.”

Acosta knew of Trillo and the work she had done in years previous, as she is a Philadelphia native. He later came by Scott during a project surrounding mental health put together by First Person Arts. From there, further talks about Scott’s work led to the idea of perhaps bringing the two artists together for a collaboration.

“He actually found connections between his work and Ada’s work. They had similarities in terms of not only capturing what they were capturing, but lots of synergies in their work. Although these two photographers didn't know one another, there was a similar aesthetic,” Acosta said.

The title, I Look at the World, derived from the Langston Hughes poem, also plays an important role in the exhibit’s message. Hughes, an African American poet and activist, known as the leader of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s, wrote about the world in front of him. It was sometimes not all that pretty to see.

“In, 'I Look at the World,' he makes the observations as he's looking at what is going on in America around the civil rights movement, and putting those preoccupations into words and into this poem,” said Acosta. “I thought that the title was appropriate because again these two artists were really looking at the world, what was going on immediately.”

Out of the hundreds of photographs submitted from each artist, Acosta had to narrow it down to just 22 total, which made for a difficult but exciting process. It also opened his own eyes to the similarities Scott and Trillo found in their own work.

“It's actually a collaborative process between what the photographer's themselves thought was really important about these photographs. I think that they have been filtered even further through their own lens around what they felt they really wanted to show and what I felt I wanted to show in this show,” said Acosta. “You'll see that there are some photographs that are very similar in the way that they were shot, but they were shot by two completely different individuals.”

Ceramist turned photographer

Scott is an African-American artist and ceramist originally from Madison, Wisconsin, but is now a Philadelphia native. He’s had his art exhibited around the country, in places like the Design Miami Podium in 2020, the National Conference for Education in the Ceramic Arts in Minneapolis, including having photographs of the 2020 social movement in Philadelphia being featured in an issue of the New Yorker.

When speaking on the initial inspiration to capture the movement by way of photography, he pointed to the pandemic as the catalyst.

“I’m normally a ceramist and I lost access to my studio in March 2020. And that was like the same time I was picking up the camera, but for like the first time,” he said.

From there, Scott started walking around the streets of Philly and took photos of neighborhoods and people. Initially, what started as just a new art practice to take up turned into something much more important.

In May of 2020, George Floyd was killed at the hands of three officers in Minneapolis. What followed was an uprising of the Black Lives Matter Movement and protests. The social movement happening in front of him made him want to capture the important time that it was.

“And then when the protests started is when I started bringing my camera out. After that first protest, I kind of knew that I needed to stay out and keep taking photos and keep documenting what was happening because it felt like such a big moment in history,” said Scott

He also saw how important it was for the Black and Brown people present at the protests to be the ones telling their own stories.

“It’s not good enough to just leave it up to politicians or the media or some historian down the road to tell our stories. If we tell our own stories, now we get power over our own narratives,” he said.

As the Black community took to the streets of Philadelphia to express their outrage as an already oppressed group, Scott also felt the importance of what he was documenting in the moment.

“You could see the protests were spreading across the country. I just felt the energy on that first day of protest, it just didn’t seem like people were going to just go home. There’s no work on Monday, no football game on. There’s no distractions to keep you from coming back out there,” he said.

For anyone that comes to see the photographs in the exhibit, Scott hopes they will remind them of what happened. More importantly, remind them of the issues that still loom over the community. Scott hopes the art will “bring them back to that time, and remember the urgency of the moment.”

RELATED CONTENT

Furthermore, he brings up issues that people need to be reminded of again that stemmed from the movement, such as the funding of police, mental health crises, drug addiction, violence against Black and Brown bodies, and police brutality.

“And I think things like that, those conversations are what I wanted, these photos to remind people of and bring them back to that place, bring them back to those moments,” Scott said.

With the exhibit focusing on two sets of events plaguing two marginalized communities, he points to the similarities between the two groups and the common struggles between them, and how it is shown in the photographs.

“One of the most beautiful things about this show is seeing the reflections of both sides of the room between Ada’s work and my work. One of the beautiful narratives about this show is how both groups are marching towards something. Marching towards equality, a better life, a safer future for their kids. A lot of the ideals that we're marching towards physically and metaphorically were the same ideals. And the same roadblocks in a lot of the ways were put in front of us. And seeing things like that make people aware of that, our struggles are often more similar than we think,” said Scott. “The same things that are used to keep us from a better future are the same. I think we’re reminded of that and find ways to come together on a lot of these issues.”

Scott also has a solo exhibition entitled When The Cracks Deepen, currently on display at Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens. It features photographs from the same time period as the ones in I Look at the World, as well as ceramic art that he has worked on over the last two years. The ceramic art focuses on his time in Philadelphia, the protests, and the neighborhood he lives in.

“My work is a lot about how our environment collects on us and how we carry it with us, and how we mend ourselves. Even if we’re cracked or sometimes broken, how we put our pieces back together. How we mend and bring ourselves back and become a full person,” he said.

Fighting for humanity at the border

Trillo is a Philadelphia native, but was born and raised in the border region of Juarez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas. The life experience makes her the right person to capture what she was able to regarding migration.

From documentary work to photography, Trillo’s work is part of the permanent collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She is also the recipient of the Female In Focus 2020 Best Series Award, and has had featured work in The Guardian, Vogue, Smithsonian Magazine, and many others. Trillo has also exhibited work beyond America, in many European countries, and she is focused on the humanity of people.

With work focused on sex trafficking, climate, violence against migrants, immigration, as well as race and class, her work brings attention to the often overlooked. It was an issue before the pandemic, and one the country still wrestles with today with the influx of migrants and the troubles they face. By way of forced prostitution, treacherous paths to the U.S., and mistreatment at the border, her work sheds light on a group of people that the country often deems not worthy.

When speaking to Trillo about the inspiration and influence to involve herself in this collaborative effort, she pointed to the curator himself.

“The inspiration was from David Acosta, he’s the curator and the one that came up with the idea. It was a brilliant idea because it’s a way to do both groups that have been separated for a long time,” she said.

While all photographs are powerful in their own right, one in particular that sticks out features a migrant crossing a river on crutches.

“As I was walking the river with them, I could feel the moment, the sacrifice of these people because he had to swim all the way across. And then his friend gave him the crutches at the end, because the river has little stones at the bottom. So there was no way he could use the crutches to cross the river,” Trillo said.

Similar to Scott, she hopes the exhibit will shed more light on the groups and help people understand the humanity of both struggles. That is something that often lacks when others speak on them.

“They have to learn respect for our communities, both Issac’s and mine. And the sacrifices that are made, and the challenges we face. I think that our community has to learn how to unite because if we unite, then we’re stronger,” Trillo said.

LEAVE A COMMENT: