Philly’s Ballet Maestro

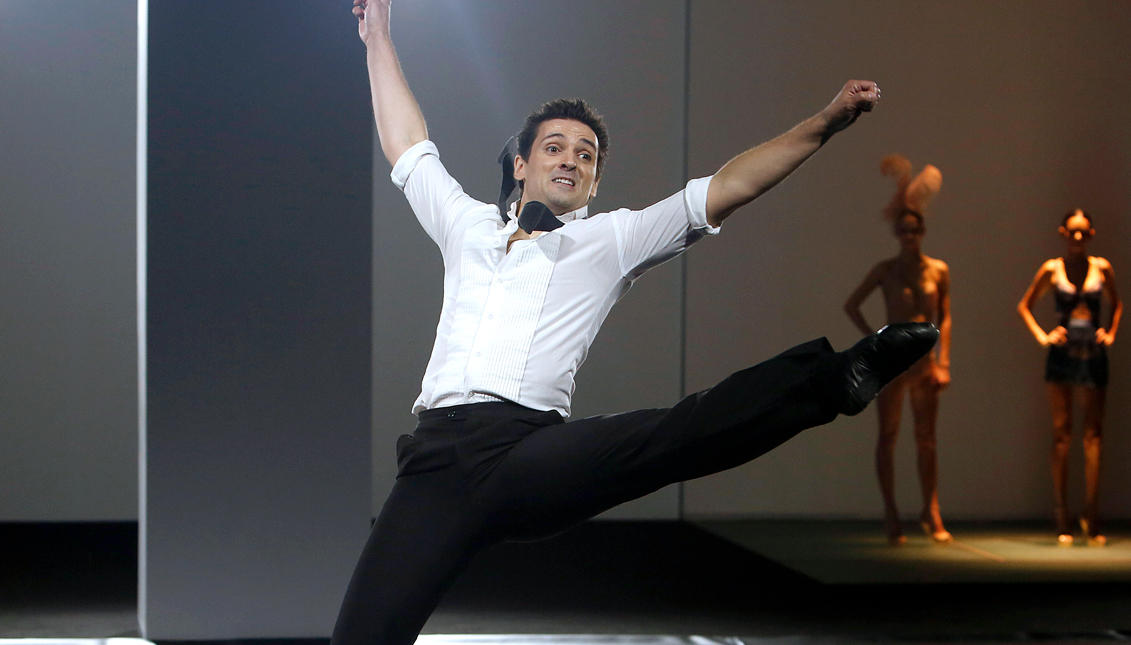

Ángel Corella is an icon in Spain, and today, he is the artistic director of the Philadelphia Ballet.

Growing up in Madrid, Spain, Ángel Corella was an energetic kid. He describes himself as a happy child who was surrounded by family and loved dancing.

To exhaust his energy, Corella would end up doing ballet with his two oldest sisters, a non-traditional activity for a young boy in Spain, especially at the time.

In a conversation with AL DÍA, Corella discussed his career in ballet, and it all began with a short-lived karate career:

“One of the kids in the [karate] class got his nose broken... So my mom used to take me to ballet class with my sisters,” said Corella. “She used to say, ‘sit down here, because I have to go do some errands, and I’ll be back.’ She thought she was gonna find me up on the roof because I couldn’t stay still.”

To her surprise, she returned to find the young Corella sitting still, watching intently, intrigued by the ballet lesson.

Once, when Corella’s mother was speaking to a teacher about an end-of-year recital, Corella got up, started to do turns and jumps, and danced around.

At two-years-old, Corella would dance like John Travolta, mirroring the actor at a time when Saturday Night Fever’s soundtrack was occupying storefront radios.

“I still had the pacifier in my mouth, so I think for me, it was always easier to express myself through dance than words,” said Corella. “It was always easier to show who I was and how I felt through ballet.”

Corella would go on to dance with his sisters until he was about 13-years-old. Around this age, the dancer started getting teased and bullied at school. Corella recalled football and bullfighting being of the utmost importance, and ballet having no room among the interests of his peers.

In the Corella household, Ángel’s mother was an artlover, a writer who appreciated opera, ballet and music. One sister would later become a dancer at the American Ballet Theatre, and his oldest would go on to be a hair and makeup artist.

While his mother had the strongest influence over his decision to go into ballet, Corella’s father — once a boxer — had worries over how others would react:

“The first time [my father] saw me dancing at the Metropolitan Opera House, he said he was crying all the way through, because he was so emotional about it,” said Corella. “But at the beginning, he knew I was going to have problems at school, when kids found out I was a ballet dancer… and he was right.”

There were no ballet companies in Spain when Corella finished his initial training, so for a time he was out of work.

He considered going into carpentry, explaining that he enjoys fixing things to this day, but a friend’s suggestion to enter a dance competition put him on a different path.

Originally reluctant to enter, Corella found himself at a dance competition in Paris, where he was shocked to win the Gold Medal and the Grand Prix.

A member of the jury suggested Corella try his chances at the American Ballet Theatre. The dancer then traveled to the United States to do just that.

When Corella arrived in New York at 19 in 1995, he was alone and overwhelmed.

For the first time, he wasn’t surrounded by family, and was confronted by an unfamiliar language, having studied French in school.

His anxiety subsided as the Metropolitan season began. As he began dancing in America, the audiences’ warm reaction made him feel at home.

“I started to learn English really quickly… It was a tough beginning, but then it was quick… I adjusted to the city, adjusted to my new life.”

When Corella left Spain, his father had recently lost his job. Corella gathered some income from extra performances and galas to open a ballet shop in Madrid. The shop, run by his parents, sold ballet attire, such as tutus and leg warmers. Successful, they would later open another shop in Barcelona.

Many dancers would approach the Corella family and ask for advice on pursuing a career in dance abroad. Upset over the lack of options for dancers in Spain, Corella was influenced to establish more of a presence for ballet in the country.

“I decided to create a foundation... to start funding money to start a company. In 2007, we gathered enough support to be able to open the company,” said Corella.

The company, The Barcelona Ballet, toured New York, Mexico, and Portugal. The company was set to tour China, but when the political party changed in Spain, support for ballet shifted.

“A new color party... decided they didn’t want the ballet anymore, so they took all of the support away, and we had to close it,” said Corella. “I had to sell everything I had at that time. I had to sell my house, my car… to be able to pay all the dancers.”

Corella was still dancing up until the closure of his company in Spain, but around the same time, he decided to retire from his dancing career.

Corella’s time as a dancer ended with a performance of Swan Lake at the Metropolitan House in New York. He was 37-years-old.

Corella found it difficult to leave behind the audience’s positive energy, and their reactions to his performances, but for him it was time:

“It really felt like I closed that cycle of my life, closed that chapter, and then I opened a new one that would be directing the [Philadelphia Ballet] and sharing all that knowledge that I gathered through the years to the new generation. I was really happy and really ready to do that,” he said.

He is now a stager, choreographer, spectator, and coach.

“I think it’s important to know when your time is done and it’s time for someone else to take your place,” said Corella

Corella wasn’t planning on directing another company, but after he saw the opening for an artistic director at the Pennsylvania Ballet (now known as the Philadelphia Ballet) in 2014, he applied.

After two interviews, Corella got the gig. Due to timing, the dancer believes it was meant to be.

“I loved the city, and I loved what the company stood for… I was quite happy, and it’s been seven years now… it feels like it was yesterday.”

“I loved the city, and I loved what the company stood for… I was quite happy, and it’s been seven years now… it feels like it was yesterday.”

RELATED CONTENT

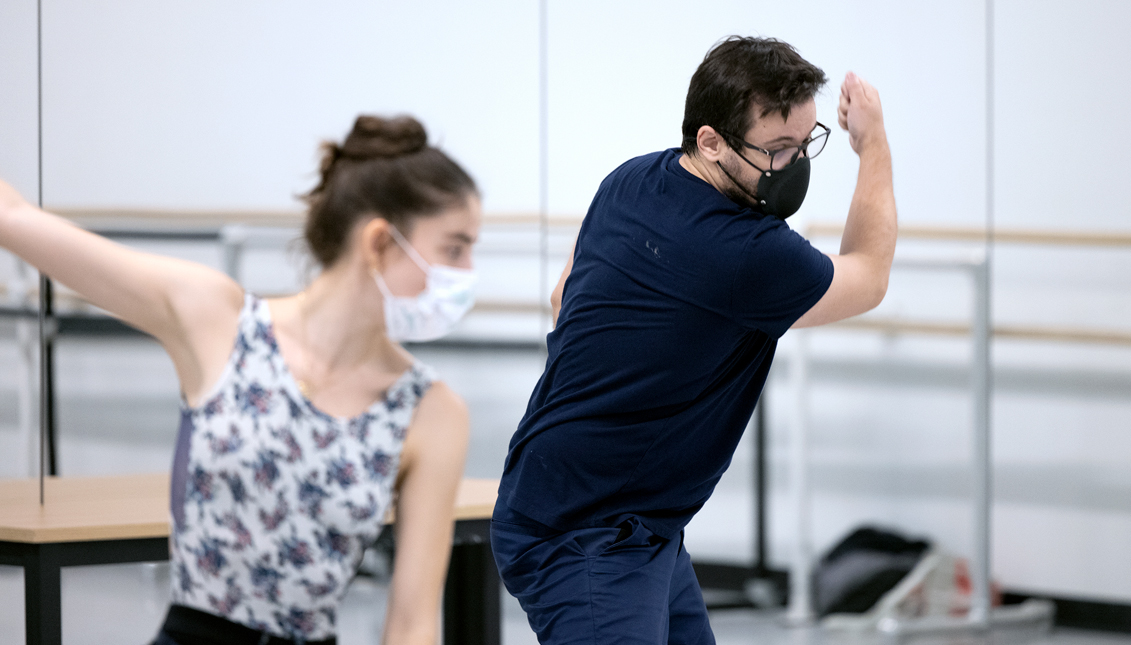

First on the agenda, after becoming the artistic director of the Philadelphia Ballet, was to address the dancers, re-energize them, and re-energize the company.

“[I] danced with… companies all over the world. I knew what kind of energy and what kind of artistry was going around the world, so I tried to implement that into the company,” said Corella.

In some cases, he was reluctant at the beginning, saying that when things have been done a certain way for a long time, people form a tendency of falling into patterns.

There was a little bit of resistance, but Corella had two years with the dancers to figure out who did and didn’t want to be part of the new direction. After two years, some people left, some would not renew their contracts, and soon the company developed to where it is right now.

“I wanted to make the dancers into movie stars... so everyone can recognize, in the city… who the dancers are so they can actually relate to them and want to go to the theater to see them,” said Corella.

Corella wanted to take the company on tour to achieve a more international presence, and to be regarded alongside other arts organizations such as the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Opera of Philadelphia.

“That’s one of the reasons why we changed from Pennsylvania Ballet to Philadelphia Ballet, because I wanted to be part of that anchor of Philadelphia’s most important arts organizations. I think we have done that in the past six years,” said Corella.

He cites patience and listening as virtues learned from working with the Philadelphia Ballet, as people put in better work when their ideas are heard, and when they are part of the decision-making process.

It’s difficult to predict the future of dance and ballet, according to Corella, because the culture is always shifting.

When it comes to the Philadelphia Ballet, Corella wants the process going forward to unfold naturally, while keeping the focus on the Philadelphia arts community.

“Everything will come with us into the future of Philadelphia Ballet, but I think it will be important we represent the city we live in, the city we train in, the city that sees us,” said Corella.

On a more global scale, and particularly in Spain and Latin America, Corella is hopeful of dance and ballet’s ability to flourish.

When asked how to get more Hispanic and Latino people involved in dance, Corella said:

“In most Hispanic countries, dance is not something that’s part of their heritage or their culture. I think through outreach programs, and our department of outreach is doing an amazing job bringing ballet to all those schools.”

Corella believes parents should be supportive if their child decides to go into the arts, as there are many misconceptions on what the arts, ballet, has to offer, both professionally and artistically.

“There’s a preconception of what ballet is, what classical ballet is, for Hispanics, so it is something that we’re working on trying to change for the future.”

The work needed to eliminate inaccurate preconceptions surrounding ballet are sizable, but Corella knows this better than anyone:

“One person can make a change, but in most cases it needs more than one person… Being the artistic director of an organization like the Philadelphia Ballet, it would be crazy if I could say it’s all done by me.”

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.