Stringing Together The Life Of A Wandering Musician

Roberto Díaz, a Chilean immigrant, has made many moves throughout his career as an esteemed violist and as an educator. Now, he is the President and CEO of The…

Exhilarating crescendos, robust timbres, and the build-up to a thunderous, emotional finale.

Just as Roberto Díaz opens his eyes from the spell he’s cast on himself and his viewers with a four-stringed wand, the audience claps politely- the classical concertgoer’s version of roaring whooping -and he takes a gracious bow.

Whether in a viola sextet, a chordophone quartet, or swiftly strumming his bow accompanied by a pianist, Díaz utterly transfixes the spaces that he plays in with not only his music but also his gentle demeanor and overt passion for performance.

The CEO and President of The Curtis Institute of Music (one of the most selective institutions in the world), has had many an opportunity to remain a permanent fixture on many of our nation’s elite and revered stages.

But, despite receiving applause in Boston, Minneapolis, and Washington D.C., a love that transcends beyond intonation and pitch led Díaz to prioritize music education and the formation of the next generation’s great composers and conductors above all else in his prolific career.

This is the story of an immigrant who has impacted The United States through sound and spirit.

Is talent hereditary?

At least in the case of the Díaz family, a resounding “yes” would be appropriate.

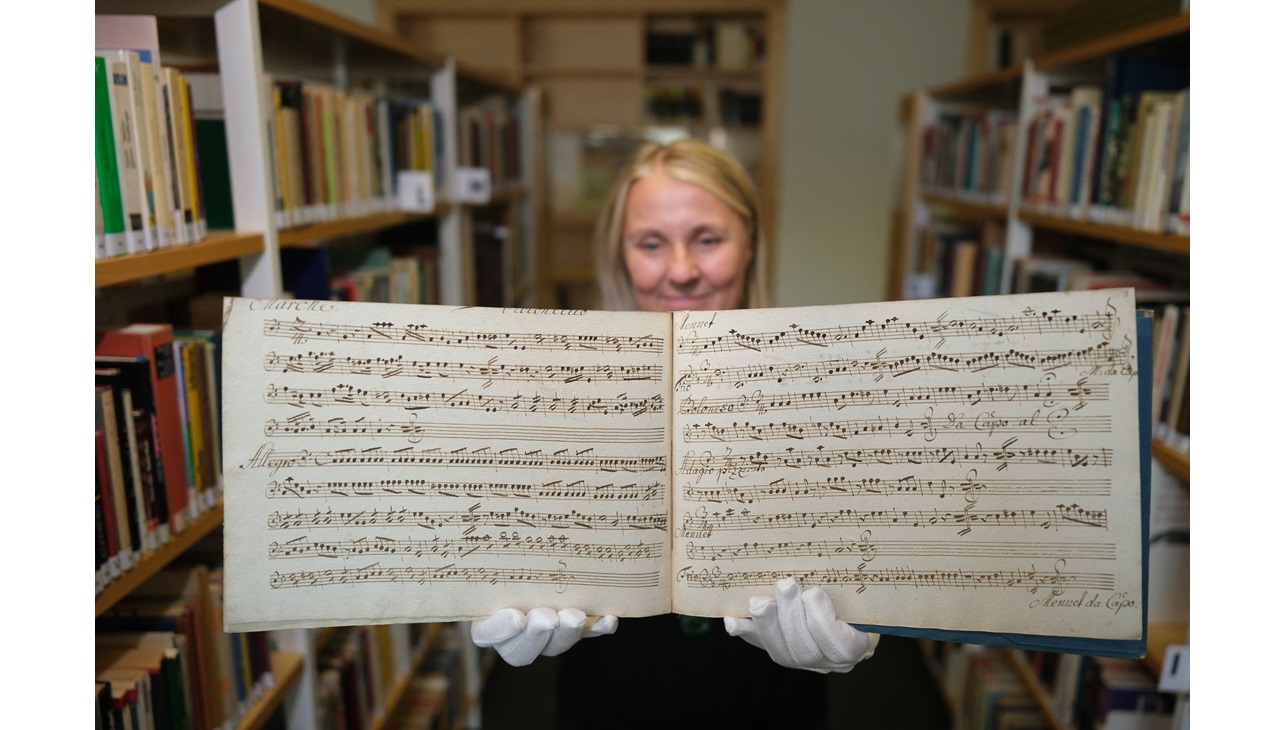

Roberto was born to two professional musicians in the capital city of Chile- Santiago -in 1960. His father was the principal violist at the time for the Chamber Orchestra of The Universidad Católica, and his mother was a pianist who studied with the likes of legend Claudio Arrau León.

Naturally, the value of a rigorous musical education was something that the Díaz parents took seriously.

All three of the Díaz siblings were subjected to hours of learning and practicing, and though it was “not necessarily” to follow their parents’ footsteps, two of the Díaz kids ended up becoming virtuosos in string instruments. Roberto took after his father’s viola prowess, while Andrés mastered the cello.

Later, the brothers would have the rare and heartfelt opportunity to play together in a trio, called The Díaz Trio in spite of its third member (Andrés Cárdenes) not being a part of the family tree.

Roberto’s first time in the States would be in 1966.

The Díazes found themselves in Bloomington, Indiana for a year due to his father, Manuel, being offered a Fulbright Scholarship to study under the wing of Scottish violist William Primrose, whom Roberto considers to be “one of the best” ever.

There, the siblings learned how to speak English. At the time, he did not know that the language would become useful, for this would be just six years before he would make a move that would change his personal and professional life forever.

On the 9th of September in 1973, merely days before the violent coup d’etat that would ultimately end Salvador Allende and bring Augusto Pinochet’s reign into effect, the Díaz family parted ways with Santiago and flew to Atlanta, Georgia.

After graduating from high school in Atlanta, Roberto attempted to disregard the talent he had been bestowed by nature (and, of course, by nurture), and studied industrial design. Upon receiving his degree, he accepted the reverberant call of a musical vocation.

“There’s been a lot of running around [in my career]. I’ve been very lucky. I think my career has been multidimensional, if you will. I played at orchestras, I taught in different schools, I played chamber music, I was able to play solo concerts, and I even got to play with my brother! This life has taken me to Europe, all over Latin America, and to other parts of the world.”

In the United States, it took him to The New England Conservatory, the Curtis Institute of Music (as a student), the Boston Symphony, the Minnesota Orchestra, the National Symphony, and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

RELATED CONTENT

“Your opinions change, your tastes evolve, and you start to play for different reasons at certain points in your life. I think, in many ways, the life of an artist means always being aware of different opportunities to learn from different experiences.”

On one of those experiences- a music festival in Cape Cod -Roberto would meet his wife, violinist and fellow Curtis alum Elissa Lee Koljonen. Together, they both have two children and enjoy walking their dog on Haverford College’s lush nature trail.

When asked whether or not he faced significant obstacles in the music business for being Latino and a non-U.S. native, Roberto had only gratitude to express for the progressive nature of the “art world”:

“I think that, historically, the ‘art world’ has been, in many ways, quite ahead of other sectors- if you will -as far as tolerance because talent is talent. Where they’re [the artists] are from, or their personal beliefs, or their sexual orientation… People don’t pay quite as much attention. Most orchestra positions have “blind” auditions. You’re behind a screen, so the judges are just listening to how a person plays.”

Roberto also partially attributes his comfort and sense of belonging in U.S. ensembles with the fact that, as a light-skinned Latino, he doesn’t “look” like he could be from anywhere else.

He did point out that, nevertheless, his accent and his last name are a “dead giveaway”.

“As someone that is from a different part of the world, diversity in the art form and diversity in our students is something that I am very committed to. Curtis is a very international school and quite diverse as is, but that isn’t to say that it can’t become more so.”

One of the main ways that Roberto has proven to be an advocate for diversifying the arts has been through the implementation of Curtis On Tour in 2008, a program that takes Curtis students to perform and collaborate with other budding musicians in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. “This is a great program for recruitment purposes, but also to promote the fact that music is an incredibly inclusive world to be in”, Roberto rhapsodized.

Diversifying Curtis also includes ensuring that the institute of music is keeping up with the times and evolving as curricula and the proliferation of music has rapidly done so, while simultaneously staying true to honoring tradition and the canonical.

“Classical musicians have a lot to learn from, you know, what is seen more as pop music or music of other types. There is a tremendous appetite for what we do, but not necessarily presented in the formats of the past, such as two-hour weekly concerts. This is why I say that advocacy is a hugely important lesson for our students. I don’t think anyone is a better advocate for music as an art form than a young person.”

For Roberto, artists have a tremendous responsibility for their community, both the one that they play in and the one that they live in. He is an outspoken proponent for developing Curtis’ students wholly, enriching both their musical and people skills by instilling the values of social responsibility, tech-savvy, education, and most of all, “emotional intelligence”:

“Picking your battles, knowing how to engage people in saying them and making them go this and this direction is just as important for artists than it is for business people.”

When Roberto isn’t in the classroom or in the concert hall, he is philosophizing about the impact of music in society as a member of The American Philosophical Society, the oldest of its kind in the country. Founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin, the A.P.S. is committed to “promoting useful knowledge”, and Roberto uses his administrative position at Curtis to do so for his eager protégés and for their future audiences.

“Music is not just an improvement [to society], it is a necessity. Ultra contemporary, rock, pop, rap, classical music, it’s the language that everyone understands.”

What does Roberto not like about music?

When it’s his, and it’s being played in the background at dinners or at parties.

“It drives me crazy!”

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.