50th Anniversary of St. Basil's Protests: Chicano Catholics' Night of Broken Glass

Long live the race!, shouted the Chicano activists in front of the opulent church. Can a shepherd who forgets his blackest sheep remain a shepherd?

It is Christmas Eve in the year of Huitzilopochtli, 1969. Three hundred Chicanos have gathered in front of St. Basil’s Roman Catholic Church. Three hundred brown-eyed children of the sun have come to drive the money-changers out of the richest temple in Los Angeles. It is a dark moonless night and ice-cold wind meets us at the doorstep. We carry little white candles as weapons. In pairs on the sidewalk, we trickle and bump and sing with the candles in our hands, like a bunch of cockroaches gone crazy.

The Revolt of the Cockroach People, Oscar Zeta Acosta.

When the St Basil's trial began, Oscar Zeta Acosta was not a mere activist, but the protesters' lawyer and one of the best-known Chicano civil rights fighters of the time alongside Cesar Chavez, the leader of the Chicano peasant movement.

He was writing a history of Los Angeles, and that Christmas Eve, 1969, he was meeting in front of St. Basil's Church to claim alongside three hundred Mexican Americans that Catholicism had turned its back on poor Latinos.

"We have committed ourselves to one goal: the return of the Catholic Church to the oppressed Chicano community," Richard Cruz in 1969.

The way they were repressed showed that they were not wrong.

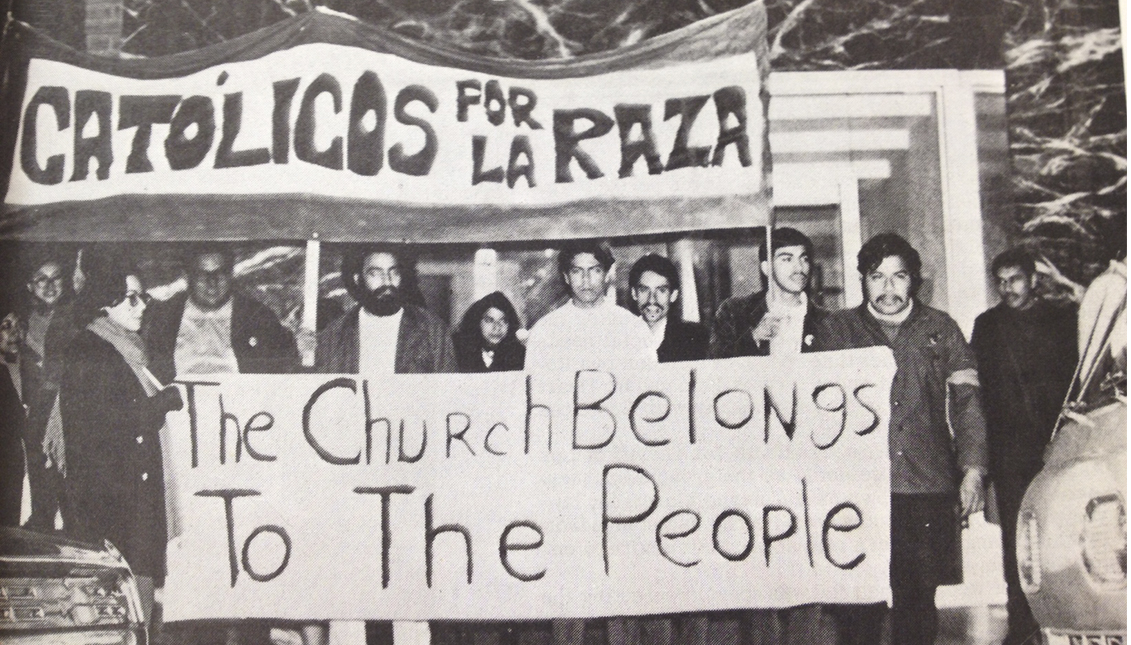

They wanted to get into the midnight mass and confront the then Cardinal James Francis McIntyre with the neglect of the institution. The group was comprised of Richard Martinez and supporters of Católicos por La Raza, who linked their "Aztec" heritage to their faith in Catholicism.

But when they arrived, they were met by a handful of police officers. By force, they were kept out. Martinez remembers the screaming, shouting and chants of the people with candles in their hands demanding, "Let the poor in!"

Twenty people were arrested in what was called a "riot," according to LA Times archives.

Half a century later, on Jan. 11, a retired Richard Martinez and other former members of Católicos por la Raza gathered at the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany to commemorate the historic date.

The protests by Católicos por La Raza lasted all autumn. They were part of the large Chicano civil rights movement that advocated equality and voting, and they complained that, unlike other Christian groups such as the Presbyterians or the Baptists, Catholic leaders were rarely at the forefront of social justice movements.

They had tried to meet with McIntyre before, even organizing a rally at the cardinal's residence and a prayer vigil on Thanksgiving Day. But when about 30 members of Católicos por La Raza forced their way into the cardinal's office on December 18, God's angry representative "for a few" reluctantly promised to investigate what the congregation and students were demanding.

"It was the first moment in which a bold, brazen and fearless youth movement confronted the Church," Professor Felipe Hinojosa.

A week later, there was still no news from McIntyre.

"We have committed ourselves to one goal: the return of the Catholic Church to the oppressed Chicano community," announced the head of the organization, Richard Cruz, at a press conference.

What they wanted, he said, was for the institution "to become as radical as Christ."

They hoped to reform the church but were sentenced to four to six months in prison for attempting to enter the church by force during religious service. However, those who took part in the St. Basil's Protests believe that their affront led to changes in the archdiocese.

RELATED CONTENT

Cardinal McIntyre retired in the early 1970s. He was succeeded by Archbishop Timothy Manning, who soon afterward met with the Chicano group and began to take action:

One provided more social and educational funds to the community and another created an inter-parish council of all the churches in East Los Angeles to advise him. A year later, the nomination of the Ecuadorian-American Rev. Juan Arzube as auxiliary bishop of the city made it clear that some messengers of God are an obstacle and others a door.

According to the University of Texas professor Felipe Hinojosa, a specialist in Mexican American studies and religion, the activism of Católicos por La Raza was "the first moment in which a bold, brazen and fearless youth movement confronted the Church.

"Nothing like this has ever happened before, at least in the United States," he said.

The Chicano coalition dissolved shortly after the protests against the Vietnam War organized by the so-called Chicano Moratorium Committee against the war. Following violent confrontations with the police, three people were killed, including journalist Ruben Salazar.

"I hope that the energy and dynamism of the Chicano movement could be reflected in the generations that are struggling with these issues today," said Richard Martinez at the commemoration last Saturday, Jan. 11.

According to the Pew Research Center, however, the number of Latino Catholics has decreased by 10% in the last decade, while the number of atheists has grown by 15%.

Perhaps today more than ever we need to recover the spirit of the St. Basil's Protests. Can a shepherd who ignores his blackest sheep really be a shepherd?

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.