Fearless travelers: Ynés Mexia, a botanist in the heart of America

Every time a woman ventures out on a solo journey, she is still warned that she is in danger. That only gives us more reason to cross the world.

At the age of 50, with several marriages behind her and a nervous breakdown that forced her into university, a Mexican-American woman to whom plants always gave comfort became one of the greatest discoverers of rare species of the early 20th century. Those who knew Ynés Mexia saw her riding through Latin America, living with the indigenous people and facing numerous falls, poisonous berries and the fury of volcanoes.

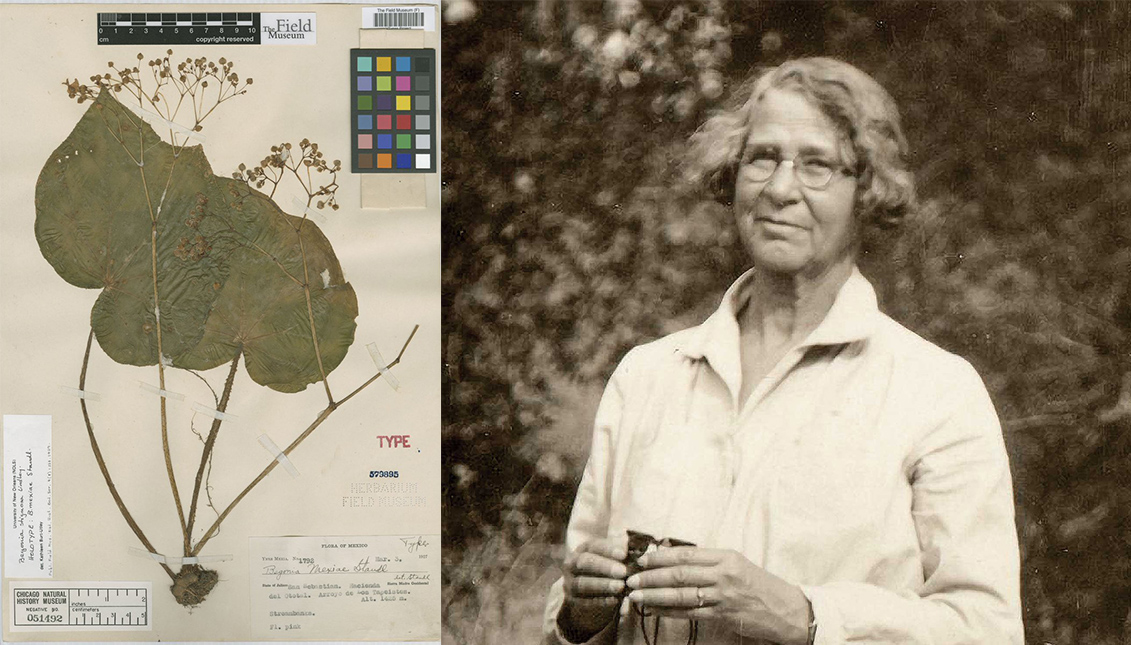

Her fascination with plants was similar to John Laroche's fascination with the ghost orchid — from Susan Orlean's wonderful Orchid Thief — but Mexia dedicated herself to classifying and ordering nature, collecting nearly 150,000 specimens and describing 500 new species, 50 of which had never been seen before. Like Mexianthus, a new genus in the Compositae family that was named after her work.

This is the story of a woman who, instead of defoliating margaritas, wanted to go and find them.

Born in 1870 in Washington, Ynés Mexia's childhood was like that of every diplomat's child, an eternal moving on. Until her parents divorced when she was nine years old, and although at first she stayed with her mother in Philadelphia, her father became ill and Ynez went to Mexico to care for him until his death. She married, became a widow, remarried, and the marriage failed. Eventually she settled in San Francisco as a social worker in her early forties, but as a result of a mental breakdown, she needed to root herself strongly in the soil and joined the Sierra Club, fascinated by plants and nature.

In 1921, Ynés Mexia, at age 51, enrolled at the University of California to become a botanist. But she never graduated, nor did she need to.

She made her first expeditions as a group, but when she was injured after a fall during a botanical exploration to Sinaloa, Mexico, promoted by Stanford University, she decided to continue her adventures alone.

Thus began the legend of a woman who spent 13 years traveling from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, crossing America in search of plants that some believed to be legendary, such as the wax palm. She faced many obstacles — not only the beautiful and fierce nature, but also the racism and machismo that prevailed at the time.

RELATED CONTENT

"A well-known collector and explorer declared very positively that 'it was impossible for a woman to travel alone in Latin America'," she wrote in an unedited article. "I decided that if I wanted to know the South American continent better, the best way to do it was to go through it," she later explained in the Sierra Club newsletter. "Well, why not?"

Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis, professor of biological history at the University of Florida, also gives an account of the stigmata that, like huge faults in the terrain, Ynés Mexia jumped over without a hitch:

"Women were actively discouraged from doing this kind of work, because it was considered unfeminine and dangerous. You actually had to camp, you couldn't wash your hair, you lived a hard life, and that could be dangerous," she said.

But Mexia was doing exactly the job she wanted to do.

Toward the end of her life, Ynés Mexia was already a celebrity invited to participate in numerous conferences about her travels, which she also reported in magazines and newspapers of the California Botanical Society. Although she died shortly after returning from an expedition to Mexico where she had fallen ill — she was diagnosed with lung cancer — part of the enormous archive of specimens she left us can be seen in the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University and at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

As the secretary of the Sierra Club once wrote in a newsletter memoir, Mexia had "that rare courage that allowed her to travel, much of the time alone, in lands where few would dare to follow."

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.