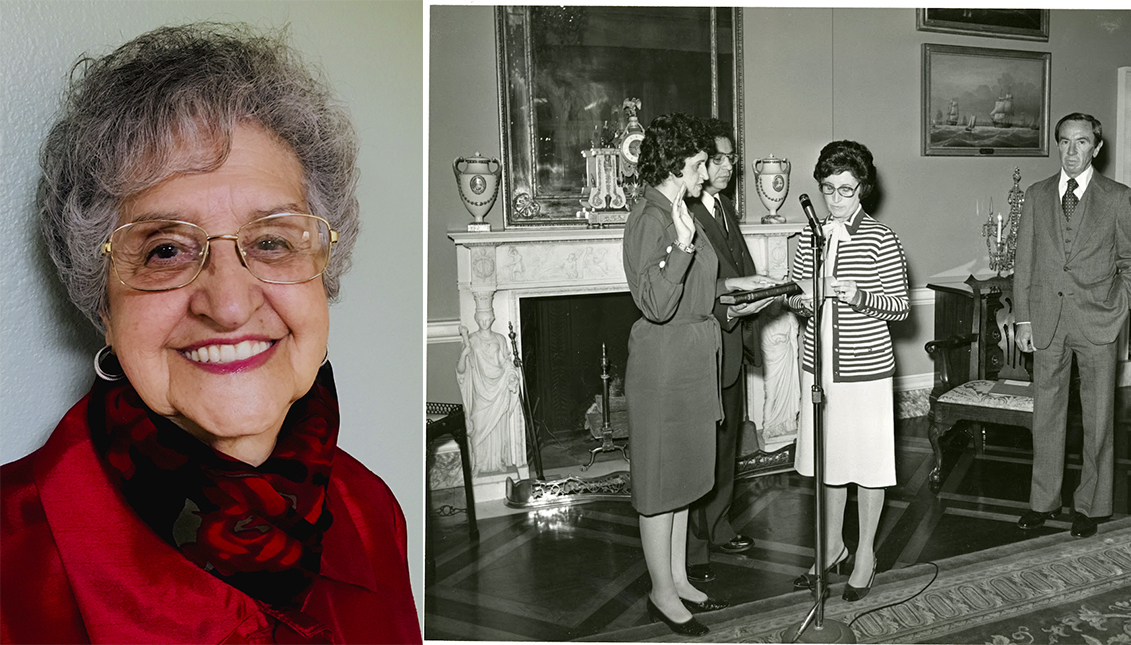

The fascinating story of Mari-Luci Jaramillo, the first Latina ambassador to the United States

She moved from poverty in New Mexico to a life of diplomacy and advocacy for the civil rights of Latinos.

The day she received a call from the U.S. State Department saying that President Carter was very impressed with her credentials and wanted to offer her the post of U.S. ambassador to Honduras, Mari-Luci Jaramillo, an ESL professor at New Mexico Highlands University, was so surprised that it took her some time to process the news.

Until that moment, she had always thought to be a diplomat, you needed two things: political connections and money. She lacked both. She didn't even know very well, as she admitted years later in an interview, what the tasks of an ambassador were. Of course, she had done a lot of work as a civil rights activist for Hispanics, but did Carter really consider her?

It was 1977, and President Carter was rushing to have a new ambassador in Honduras because the post had been vacant for several months and chaos was beginning to emerge at the embassy. If she accepted the post, Mari-Luci was told, it would not be an easy process; she would have to appear in court, be investigated by the FBI and, above all, keep it secret until Carter made the announcement. The only person she could reveal the future nomination to was her husband.

"Slow down." "Slow down," her husband begged as he drove home.

They were both sitting in the car and she was talking like a crazy person. They were both working as teachers on the same campus and had arranged to meet urgently after a hurried call from Mari-Luci where she was trying to explain her situation.

"And what did you tell him?" he asked.

"I said no."

"You said what?" he said, taking the key out of the ignition.

"What would happen to us, if I were the breadwinner of this family? You would feel very bad," said Mari-Luci.

And then he answered something that the future ambassador would never forget:

"I know who I am, Mari-Luci; I'm a very confident person. I think it's a courtesy of you to tell the president that you would love to be considered for the position."

That's how a young Hispanic woman born into a humble New Mexican family became a diplomat.

More than that: Mari-Luci Jaramillo was the first Latina to become an ambassador to the United States, a position she held until 1980, and the first woman to head an embassy in the Western Hemisphere.

RELATED CONTENT

She knew that the international media would destroy her for her lack of political experience and the military would look down on her for being a woman, but Mari-Luci managed to take advantage of both. Like her experience as a teacher and her humble origins in a minority family, she was able to change what wasn't working at the embassy outside it and in Honduras.

"I got involved," she recalled during an interview. "If there was a sick child, I would get on the phone and call directly: 'I heard that so-and-so was sick, how is he today'. Not only did I do this with the embassy staff, but while making my courtesy calls, I did the same with the others. For me, it was just an extension of my campus."

She worked from the very first hour, which is very unusual for an ambassador, and was outgoing and affectionate. If someone didn't do their job well, she would frown as much as a teacher would.

Soon, Mari-Luci began making friends among the military, businessmen, farmers, journalists... She got involved in the country's problems and ended up being the symbol of the struggle for women's rights and a powerful Hispanic who demanded that Latinas take a more active role in society.

Meanwhile, her husband was diligently running the household during the three years that Mari-Luci was the leader of U.S. diplomacy in Honduras.

Upon her return to the United States, Mari-Luci Jaramillo was part of advocacy groups and boards such as the National Hispanic Cultural Foundation.

She wrote her first book, Madame Ambassator, in 2002; which was later followed by Sacred Seeds.

Among the many awards she received are the U.S. Pentagon's Distinguished Citizen Award, the Medal of the Order of Francisco Morazán and the Dual Citizenship Award for extraordinary achievements in Honduras, as well as the Anne Roe Award from the Harvard School of Education and the Elizabeth Payne Cubberly Scholar Award from Stanford University.

She passed away in November last year at the age of 91, but her legacy lives on more than ever.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.