Thirty-five years without Juan Rulfo

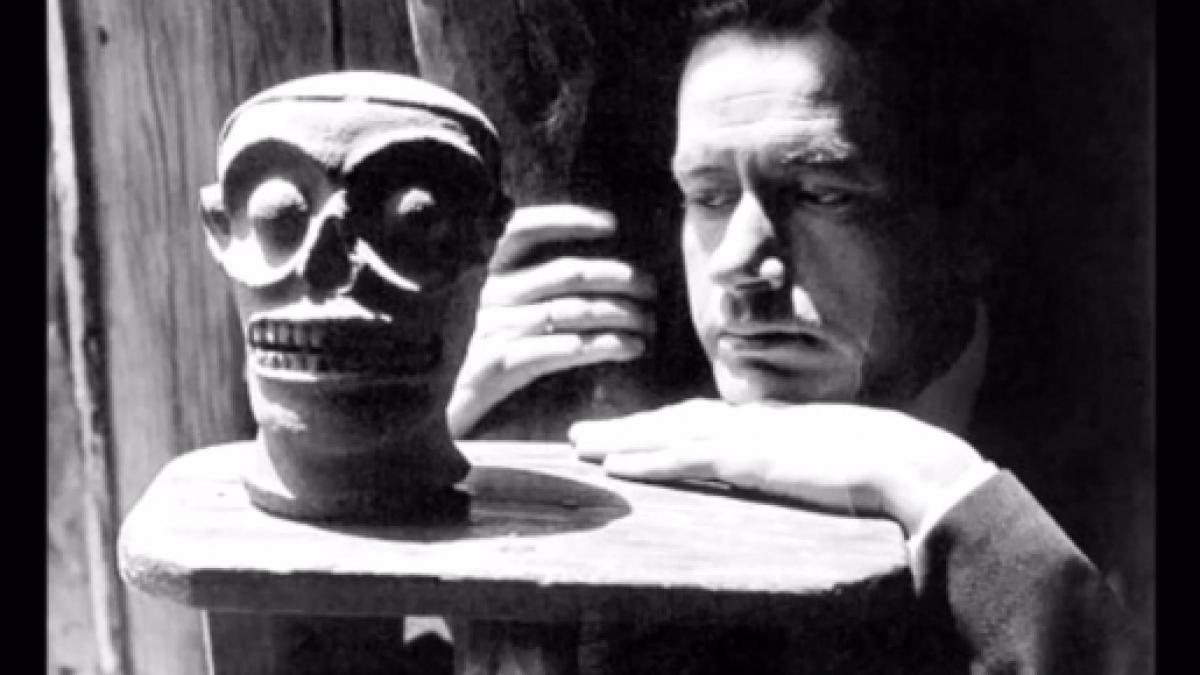

A pioneer of magical realism, the Mexican was not only an exceptional storyteller and novelist but a scriptwriter and photographer.

There are two novel openings that every literate knows by heart. One is the beginning of One Hundred Years of Solitude, by García Márquez, and the other, the phrase that opens Pedro Páramo (1955), the superb and only novel by Mexican author Juan Rulfo that was censored in Spain during the dictatorship:

"I came to Comala because I was told that my father, a certain Pedro Páramo, lived here."

There is a fairly widespread idea that Rulfo only wrote two works — the other is the short story book The Burning Plain (El Llano en Llamas, 1953) — and then, for more than twenty years, he spent his time trying to justify his "creative drought" in the face of everyone's insistence that he should keep writing. He often said people only wanted him to write a bad book.

However, Rulfo — who for some embodies a mysterious character of Comala's ghostly villagers — did continue to create, and his superb imagination encompassed much more than the pages of a book. The seventh art was his great passion (and it kept his fridge full).

In a haughty article published a few years ago in Milenio, Roberto García Bonilla cited how film and photography became essential to Juan Rulfo (1917-1986), from the years he spent in an orphanage in Guadalajara and beyond when he entered the seminary from he was later expelled for failing Latin.

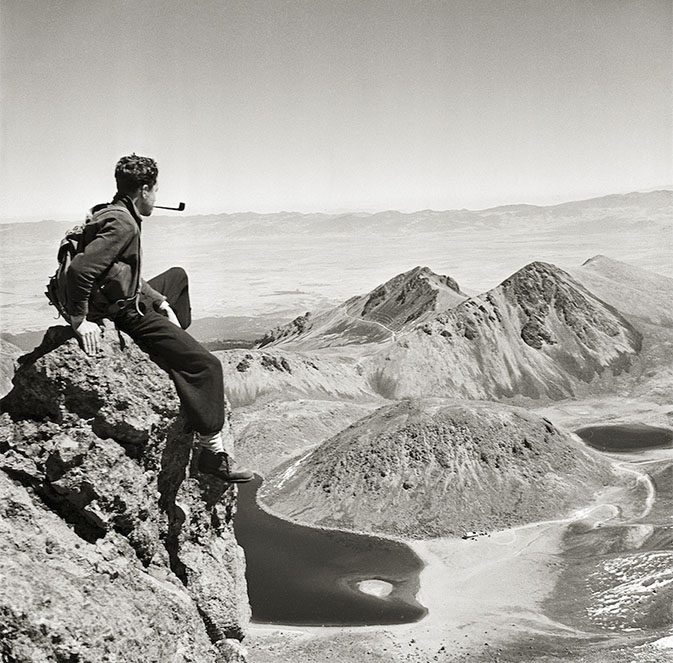

"I had a little box-like Agfa camera," the writer, who had already won some photography prizes, recalled. "It cost me eleven pesos and was second-hand. The development and printing were done in the Julio laboratories in Guadalajara. They were in front of the cinema".

Although the Mexican always maintained that both photography and literature were mere hobbies for him, both fed each other and found in cinema the best way to pay tribute to the filmmakers he adored, such as Frank Capra or Robert Siodmak and his The Spiral Staircase.

Perhaps also because the film writer can keep his anonymity much better than the novelist — he lacks the petulance imposed on the book and its author — and is a much more profitable profession. In fact, Rulfo made a living writing scripts and commercial adaptations, like Faulkner and many others, did. He also worked as a film supervisor — that is, someone who had to look for scenes that denigrated Mexico's image in movies — a position that was also performed at some point by authors such as Elena Garro and Carlos Fuentes.

"I was supposed to watch that all the Indians and the farmers who appeared on the screen wore huaraches so that people in Mexico wouldn't think they were barefoot, and I ended up having them buy huaraches for everyone in town," Rulfo recalled.

In 1955, the Mexican participated in the filming of La Escondida, by Roberto Gavaldón, an adaptation of the novel by Miguel N. Lira, where he supervised the historical verisimilitude of the film. He also photographed well-known characters of the time, such as Lira himself and the actress Maria Felix.

RELATED CONTENT

Rulfo and Gavaldón made the documentary Terminal del Valle de México, climbing on the roofs of the cars and flying over Mexico City in a small plane, to capture more than a hundred pictures of trains and stations that rarely appear in the brief biographies of Comala's author.

He also participated in the script of Paloma Herida (1962), a Mexican-Guatemalan film directed by Emilio Fernandez and scarcely documented by the press. He wrote, or rather "assembled" in an experimental way, a text that served for the short film El despojo (1960) and whose dialogues the Jalisco native invented as he went along during the shooting.

According to Garcia Bonilla, the text read in off by Jaime Sabines in the medium-length film The Secret Formula (or Coca Cola in the Blood, 1964), considered one of the best films in the cinema, was also written by Juan Rulfo.

Many of these texts used in the cinema were published in 1980 along with The Golden Rooster (El Gallo de Oro), a novel written by Rulfo shortly after Pedro Páramo and which he always disdained, considering it a bad story and a script.

Even though the Mexican adapted many novels to movies, he was very reticent about adapting his own. And no wonder. As a photographer and writer, he felt he was losing control of his stories.

Although he couldn't help it.

Few authors have made as many adaptations to the cinema or the theater as Rulfo, and that was the last straw for a writer as unfriendly to fame as jealous of his world.

On the 35th anniversary of Juan Rulfo's death, it is worth remembering: a scriptwriter is also a writer.

Fade to black.

LEAVE A COMMENT: