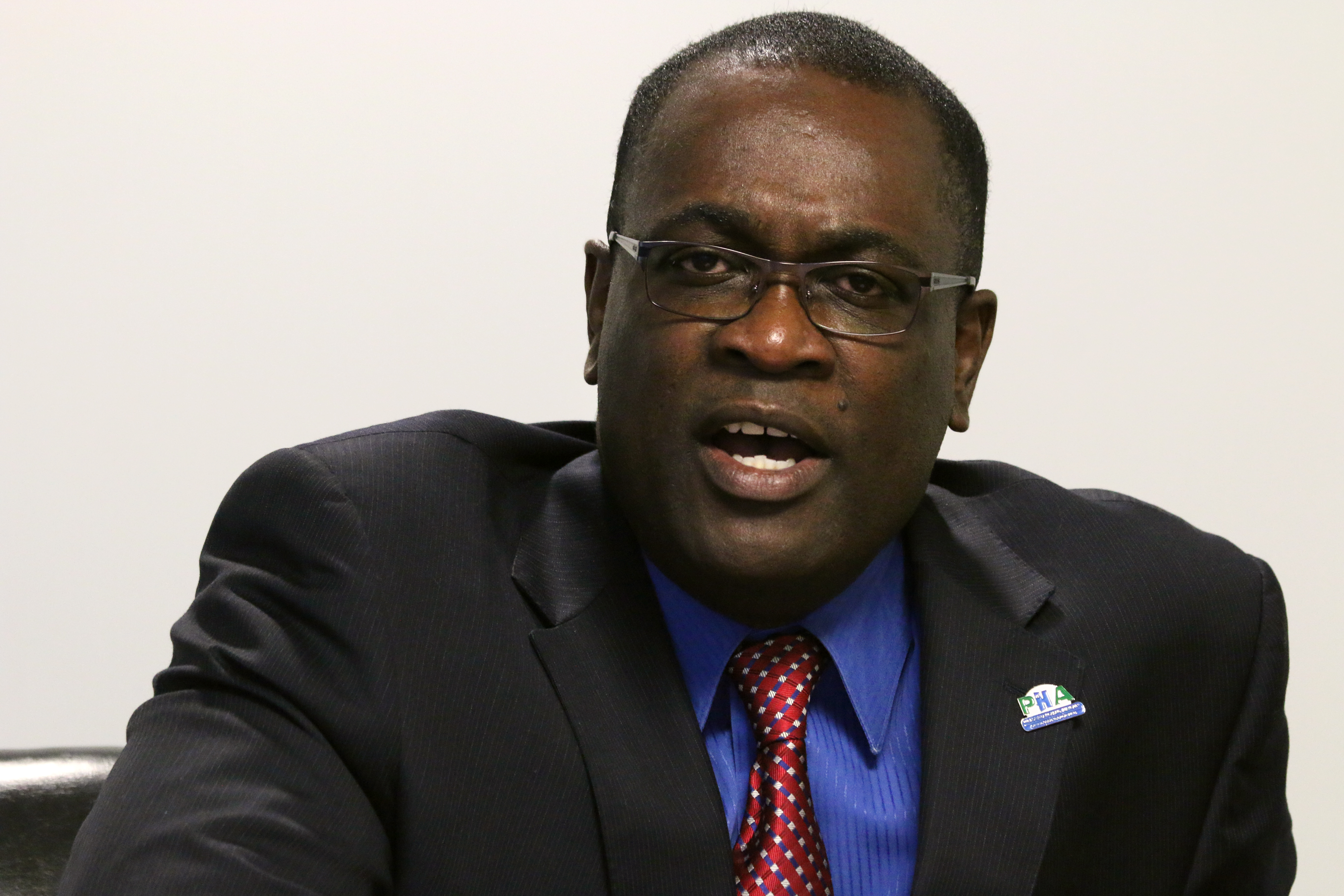

Interview: PHA president talks redevelopment in Sharswood

Kelvin Jeremiah has an immigration story.

When he was 13 years old, he immigrated to the U.S. from the small Caribbean island of Grenada following the U.S. invasion in 1983. He grew up under the former Marxist government with a bleak set of options. It was a combination of good fortune and the guidance of his great grandmother — “the smartest person I have ever known,” who hammered the values of service — which Jeremiah today credits for helping him become the CEO of the fourth largest housing authority in the United States.

Since coming to Philadelphia almost four years ago, Jeremiah has had his work cut out for him. The Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) provides subsidized housing for about 80,000 people, or about five percent of the city’s population. But the agency is also one of the largest social service providers beyond housing. Jeremiah’s mission to “help families become self-reliant” is partly through housing, and partly through services like literacy programs, job training, job placement, scholarship programs, and so on.

At a roundtable interview with AL DÍA, Jeremiah talked about growing up in extreme poverty and how it now informs his work with Philadelphia’s low-income communities. In part one of this interview, he discusses some of the praise and criticism for PHA’s massive redevelopment plan in the Sharswood section of the city. Here, a number of the agency’s problems — from battling their past reputation to negotiating with the labor unions — can be seen in context.

Part two of the interview touches on another expansion effort — that of the relationship between PHA and the Latino community. It has not always been easy. But Jeremiah says the onus isn’t just on the housing authority.

PHA provides housing to 80,000 people, which is about five percent of the city's population. What is the current status of the waiting list and the reoccupancy rate?

KJ: The waiting list is nearly 100,000. There are no requirements in terms of how long you can be in public housing, [which] highlights some of the public policy issues. You have families who are in public housing for two or three generations, in some cases 70-plus years. In terms of an annual turnover, we have approximately 400 units that are available for reoccupancy every year. As a result, because folks are not leaving, it is taking approximately 10 years to find the public housing units. Families who applied for public housing in 2004 are just being tapped to come in. There is a huge demand for affordable housing in the city. That is part of our effort to expand affordable units.

Let’s talk about that expansion. PHA recently did the ribbon-cutting for the Oakdale Apartments — 12 units, $4.6 million dollars. That’s $380,000 per unit. Have you received any criticism about the per-unit cost when there is such a long wait list with so many people in need? Doing it at this rate seems problematic in the long run. You can’t keep up with the demand.

KJ: It’s something that’s deeply concerning to us and public housing authorities across the country. Here in Philadelphia, the construction rates are incredibly high. We’re closer to New York and Boston rates rather than Baltimore rates.

What folks miss in the discussion around why PHA would pay $380,000 per unit is the fact that we are required to pay Davis Bacon wage rates. When there are federal funds involved in any construction project, the government sets those rates. And in Philadelphia, those rates are incredibly high. Almost two years ago, I sought to negotiate lower rates.

This is a union town, obviously. The prevailing wages happen to be a very thorny issue. We’re trying to find ways to mitigate those incredibly high costs. If I was a private developer not spending a dollar of federal funds, I would be able to pay whomever, whatever I wanted. And we have private developers building units — Luxor in Center City — not paying nearly as much as we are paying to develop affordable, low-income housing. I find that problematic.

Will there be a one-to-one replacement of units at Sharswood-Blumberg?

Prior to 1998 or 1999, PHA had over 21,000 units of public housing across the city. We have lost almost 7,000 units and we’re now down to about 14,000 units. When you demolish a high-rise — at Blumberg, for example, there are 500 units — we put 55 or 57 units in its place, and so we lose a lot of units. If we could bring those units back, our statutory allocation is still at 21,000, and HUD is still obligated to fund us 21,000 units. But for the fact that we don’t have it, we’re being funded at a substantially reduced number. So Philadelphia has, in a real sense, not only lost affordable housing units, we’ve lost real money in that process.

Given the situation, why do you choose to build new houses from scratch rather than fixing up any of the city’s countless vacant properties for cheaper and on a larger scale?

KJ: I think the same concerns arise. The prevailing wages don’t only apply to new construction. It applies to substantial rehab as well...But in addition to that, the question is a good one. Because it is exactly what we’re doing. We have thousands of properties of what we call scattered sites. They were given to PHA in the 1970s. Many of them have remained vacant. PHA has been doing exactly that. You are correct, the cost to rehab those units is cheaper. But they hover from around $75,000 and could be as high as $300,000 depending on the condition of the unit, obviously...You have units where you have to put in substantial work. Yes, it’s cheaper, we’re doing and have done a lot on that front, and I expect that we will be doing a whole lot more.

We have also looked across the city for properties that PHA could acquire with some investment. It’s a two, maybe a three-prong approach. We’re preserving where we can the existing infrastructure. We’re building anew. We are rehabbing long-term vacant units across the city, particularly, if I might say so, in areas where we are trying to maintain affordability because of the changes in demographics.

You’re expanding because you need to meet the demand. You also need to expand to acquire more federal money in order to keep expanding. It’s a cycle. But two years ago it seemed you were withdrawing in certain regards. PHA requested HUD approval to auction off properties in Sharswood and Strawberry Mansion. Now, PHA is taking many of those same properties back through eminent domain. What do you tell people who want to have faith in these newfound ambitious projects?

KJ: Before I came...PHA had requested to dispose of the long-term vacant and abandoned properties. That was a decision that was approved by the then board. These properties are the same properties I mentioned earlier that were given to the PHA in the 1960s and 70s already in disrepair. From my perspective, PHA had essentially ‘land-banked’ all of these properties, and we needed to reposition them. Three years ago, we developed a scattered site repositioning strategy that called for a multi-layered approach to dispose of properties...sell them to CDCs, private developers...That changed for me when I became the receiver of the company.

What happened?

KJ: I had a visit to Blumberg-Sharswood. I’m not from the city, but I like to go out to our developments by myself. Not in a dark suit and red tie, but on a Saturday, to see what the conditions that our families are living with.

I went twice two years ago during the summer, once in the well-lit evening hours, and once at night. And it offended my sensibilities that in this very city, the birthplace of American democracy, eight blocks from [Center City], families were living in such despair.

I was confronted with entrepreneurs who were engaged in business activity at Blumberg. They didn’t know I was the president and CEO. I was driving a nice car. They didn’t know why I was there and proceeded to try and sell me something [drugs]. Then they brandished a gun and told me, essentially, in the language of the community, sir, would you please get out. Otherwise, you will get shot. You don’t belong here.

I heard from families who had children living there. Mothers described the assault of their 13-year-old daughters, the constant fear of gunshots in the hallways, the making of drugs in units. On the elevator, I was told: ‘Don’t even think about trying to take it. This development belongs to us.’

It does not.

When I left that fateful weekend, Blumberg-Sharswood became the highest priority. For every development we have, my test is a very basic and simple one: Would I want my mother, my grandmother, or my sisters and their children living here? No child, absolutely no child, should have to live under those conditions.

The community, the city, the country has had 50 years to do something at Blumberg-Sharswood. The conditions that we find there didn’t just develop. I was born in poverty. I know what it means to have a future that you believe to be bleak. I know what it means not to be afforded an opportunity. I was fortunate to have come here. But they [the Sharswood residents] have been born here, they have lived here. I couldn’t, in good conscience, walk away. I have a fundamental responsibility to every one of those families.

If you’ve been to Blumberg-Sharswood, you know. You have to see it.

Did PHA, in part, create some of those conditions in Sharswood by building the towers in the 1960s?

KJ: I take exception to that. We see a history there shaped by race riots. You see the exodus of infrastructure and a well-to-do Black middle class. You see the exodus of factories. There are a whole host of social and economic conditions that contributed to what we see.

Now, folks would have you believe that we should tear down the towers and that we should give everybody Section 8 vouchers so that they can get the hell out, and let the private sector come in and develop those units, because after all, it’s PHA’s fault.

Prior to PHA prioritizing this project, the community had fifty years to do something. I didn’t see private investment coming in. Now we are proposing to do something. And we’re giving Blumberg residents the option to return to a transformed neighborhood. As you know, it’s a super block that surround nothing, essentially. But it is very close to a whole lot of amenities right here in Center City. You have families there who don’t even know there are museums and that the Liberty Bell right here in Philadelphia. That’s what we’re trying to do.

Wherever PHA has invested in transformative projects, we’ve seen marked improvement not only in the community, but in property values surrounding the development. This is not just Kelvin Jeremiah talking; I’m happy to show you the studies. That’s what we’re trying to do at Blumberg-Sharswood. A community of choice requires certain elements. We’re going to remake it around that.

How do you rebrand and move past the agency’s bad stewardship record?

KJ: This is not the same PHA. We’re not building the same kind of housing. We’re not providing the same kind of services. And yes, it is absolutely true, we have not always been the best landlord. We have not always been the best partner. We have not always been the best neighbor. But as you’ll probably see from our strategic guide [link] we recently developed, we are remaking this agency and using its resources to strategically to create some desired outcomes. Is it easy? Are you going to make everybody happy? Probably not. But I think we’re off to an awfully good start.

Part of what we’re doing now, and we haven’t always done it, is developing commercial corridors that sustain what happens in that community. There are small businesses that will be developed on Ridge Avenue. The ones that are there we will be working to support. We are investing in building a corridor that we will put our own resources to — that is to say PHA headquarters will be on Ridge as well.

Residents will have the right to return to the transformed neighborhood once the project is complete. How do you intend to retain the community’s integrity in this transition process?

KJ: The transformation is about people...They’ve come out with a mission statement for their community that speaks to how they see the community. It’s not PHA’s vision, it is theirs, and that is what is guiding a lot of development plans.

I’m not interested in what Black intellectuals in the 1950s called social work colonialism, where we design great social welfare programs in offices like this [at AL DÍA’s office in Center City] and impose it on communities. I want the community to feel and to be in a real way part of what happens in their community, both in terms of how they see it, what their desires are, and what kind of housing they want.

Part two of this interview will be published later today.

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.