Structural racism in Latin America remains hidden under the idea of mestizaje

The Latino community is no stranger to the issues of structural racism. In fact, it is anchored in the founding ideas of the Latin American republics.

The arrival of enslaved black people in what would later be called Latin America has a painful correlation with the genocide of the indigenous communities, carried out by the Spaniards during the conquest and the colony.

As entire communities died - mostly from viral diseases brought from Europe for which the Indigenous immune systems were unprepared, but also from the forced labor they were subjected to - the colonizers sought to replace their labor force, first with Indigenous people brought from other parts of the colony and then with enslaved black people brought from Africa.

The historian Tzvetan Todorov, in The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other, takes up a description by Vasco de Quiroga -the first bishop of Michoacán- in which he tells how the indigenous people who were sold as slaves were marked on their faces -as cattle- with the marks of those who bought them.

"'They are wounded in the face for being slaves and they plow them and write on them the signs of the names of those who buy them, one from another, from hand to hand, and some have three and four signs, [...] so that the face of the man who was raised in the image of God, has become on this earth, for our sins, paper."

The relationship between race and paper will be fundamental to understanding structural racism in Latin America.

Structural racism in Latin America has the characteristic of being based on the idea of mestizaje.

There is a belief that in Latin America there is less racism than in the United States, but what happens, rather, is that it has become more visible in North America. The first reason for this is in the colony.

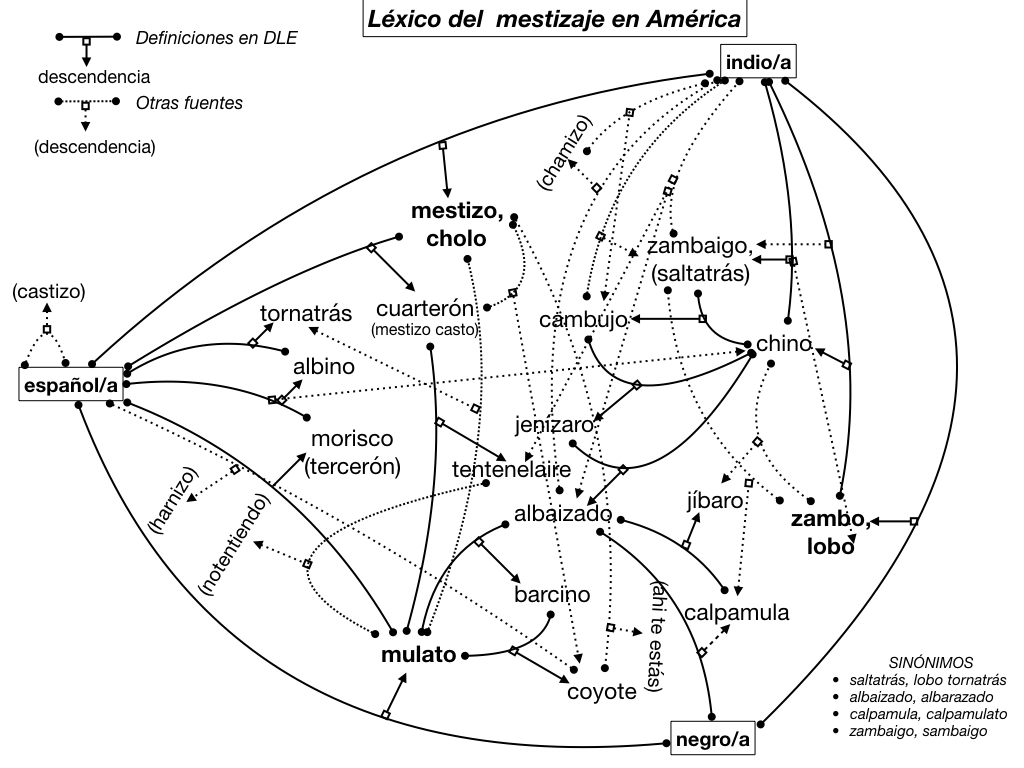

Since then, the Spaniards established in their American colonies a complex social system based on establishing a rank for each person according to their ancestry and skin: the son of a Spaniard and an Indian (as they were then called) was a mestizo or cholo; the son of a Spaniard and a black person was a mulatto; the son of a mestizo and a mulatto was a coyote; the son of an Indian and a black was a zambo or lobo (wolf.)

This complex taxonomy fed a search for mestizaje as a mechanism of social ascension, but it is also one of the reasons why the idea of mestizaje came to form the imaginary of what it is to be Latino: because from the beginning there was a language to describe the mixtures that gave way to the elements of culture that Latinos are proud of.

However, even though it gave way to the cultural elements that most distinguish Latin-ness, this recognition did not translate into a distribution of well-being.

The genocide of the indigenous communities was not homogeneous throughout the continent. Even today, it is visible that there are countries with a higher percentage of indigenous population than in others, as is the case of Bolivia, where 62.2% declare themselves to be indigenous, according to ECLAC.

RELATED CONTENT

However, the idea of mestizaje was used in the founding projects of Latin American countries after their individual independences from Spain: the idea, imposed with more or less success, that these young republics would only be successful by bringing all their members together under one religion (Catholicism) and one language (Spanish).

The taxonomy of mestizaje on which colonial society was explicitly based has been repeated in republican societies in an equally evident way, although it is not instituted as a law.

According to the report presented by ECLAC in 2018 "Situation of people of African descent in Latin America and policy challenges to guarantee their rights", in almost all countries, the afro-descendant population is disproportionately exposed to extreme poverty, higher rates of infant mortality, lack of work or study between 15 and 29 years of age and unemployment in adulthood.

In the case of countries such as Colombia, Afro-descendent communities have also been disproportionately affected by violence, particularly in areas with a low-state presence, which has had repercussions both on the presence of actors outside of the law and on the way in which they have been denied basic rights such as health and education.

In Latin America, as in the United States, Afro-descendent communities have shown their resilience for centuries and through art and have elaborated on the structural injustices to which they have been subjected. But the recognition of these merits is not enough and it has been too long since it has been necessary not only for the world to observe how they always rise, but also to stop burying them.

"Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise."Maya Angelou

Still I Rise

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.