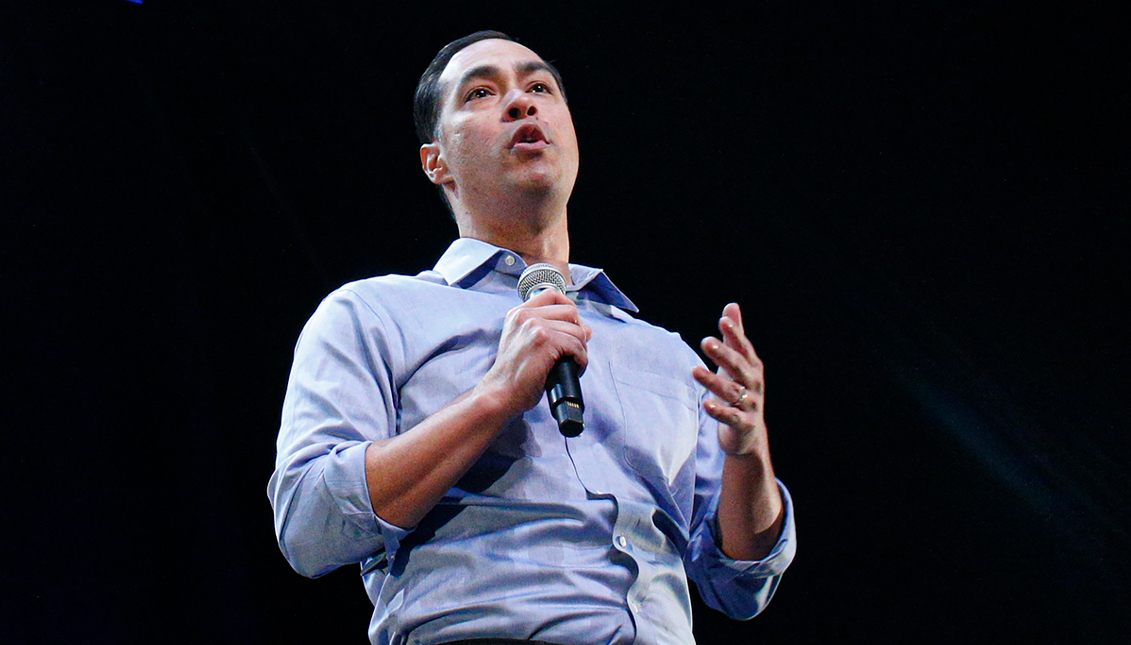

Julián Castro v. The System

“It’s going to take changing the entire ecosystem of policing.”

During the last Democratic presidential primaries, Julián Castro was the only major Latino candidate running for United States president. He was also the only presidential candidate with a police reform plan heading into the 2020 election.

More than a year before George Floyd was killed at the hands of a then Minneapolis police officer, Castro’s plan was focused on ending police brutality and was a central part of his campaign. His ‘People First Policing’ plan demanded a federal response to the police problem and an end to over-aggressive policing and racially discriminatory policing.

Castro’s plan held the police accountable.

“The margin of tolerance that they have for a Black or Brown person asking questions, for instance, about why they’re being stopped, or you know, objecting to being arrested or put on the ground, they are much quicker to act and act with more force against a Black or Brown individual,” Castro said in a recent interview with AL DÍA.

“What we see is very sad and very avoidable. And the terrible instances of police overreach cry out for much stronger police accountability immediately. And that means at the federal level, at the state level, and at the local level,” Castro said.

But the Democratic party as a whole was slow to embrace Castro’s calls for reform. His initiatives, based on the belief that the system was broken, weren’t wholly accepted by the party, and in the end, Castro halted his presidential campaign in early January 2020.

Just six months later, Castro announced the launch of People First Future PAC, to boost candidates whose campaigns run on police accountability. Soon after, he began endorsing ‘People First Policing’ candidates committed to ending police violence.

His continued advocacy for police reform caught the eye of then-Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden. Despite Castro being all-but-shunned by the party months earlier for his stance on drastic police reform, Biden asked him in June to help his campaign tackle the issue.

While the acknowledgment came late, the announcement came just as the nation was reeling in outrage at the video of Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd. At that point, Castro was an appropriate choice for Biden’s campaign to contact, as he was the only presidential candidate with a stand alone police reform plan, and had also recently endorsed Biden.

“Julián — I made a promise to George’s family that he wouldn’t just become another hashtag. We’re going to tackle this head-on — and we’re going to need your help to do it. Grateful for your support,” Biden said in a retweet of Castro’s tweet of support for Biden.

Then came the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, introduced on June 8 in Congress and later passed by the House. It’s a bill designed to bring sweeping change to police departments across the nation by addressing systemic racism and police brutality that has led to the murders of too many Black and Brown people in the U.S.

Castro said the bill largely adopts his long-standing policies of police reform, but he doesn’t take all the credit.

Before the bill was unveiled, he tweeted that the ideas put forward in his policing plan, such as ending qualified immunity and creating a database of officer misconduct, and creating a national use of force standard — “were the product of years of work by Black organizers.”

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed for a second time in the House in March, but it faces an uncertain future in the Senate, as conservatives are looking to compromise on the qualified immunity portion of the bill — a major part of it.

Because of qualified immunity, a legal shield that makes it difficult to sue law enforcement officers for wrongdoings committed on the job, many civil suits against officers end up failing in court.

But as deliberations continue, instances of police misconduct and overstepping continue to surface.

On the night of Derek Chauvin’s conviction, Ma’Khia Bryant, a 16-year old girl, was fatally shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio. She allegedly called officers that afternoon after a group of “older kids” threatened her with assault.

Details remain vague, and Bryant may have been holding a knife, but what transpired led to Bryant getting shot at least four times by an officer who failed to pursue alternate routes of mitigating a situation where teenagers are involved.

The event cut short relief of Chauvin’s conviction, as the sobering fact remained that a guilty verdict for one cop is not justice, because it will continue to happen unless the system is reformed.

And in each case, from George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, to Ma’Khia Bryant and Adam Toledo, race has always played a role.

“That’s unacceptable,” he continued. “And so what I proposed is a series of changes to policy that would help make sure that not only Black and Brown communities are safer, but everyone is safer.”

“That’s unacceptable,” he continued. “And so what I proposed is a series of changes to policy that would help make sure that not only Black and Brown communities are safer, but everyone is safer.”

In 2021, Castro is on the front lines again, advocating for police reform and urging municipalities across the country to adopt their own versions of police accountability.

Though he says this route is not ideal, because a broader, nationwide bill would be the best way to reform the system all at once. But as things stand, the probability for bills like the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act to pass the Senate is not great unless Republicans bail on a compromise.

“For too long we’ve had a patchwork of practices and policies when it comes to how police operate. And partly because of that, the bigotry and the bias that exists in our society has shown itself in how much more quickly police officers exercise force when it comes to Black and Brown communities,” Castro said.

As talks in Congress continue, there is no question that the term “police reform” is deeply polarizing, because just as other pressing topics like mask-wearing and belief in climate change, it has been politicized to the point where one’s stance determines party allegiance. It’s to the point that when a moderate or conservative hears “defund the police,” their eyes immediately glaze over without considering what it actually means.

RELATED CONTENT

Castro explained that these terms, in fact, have a vision.

“You have to put a series of measures in place... that affect the composition of the police force. How they operate, and then how they’re held accountable for mistakes they make, or for overreach,” he said.

It starts with outreach and recruitment - hiring a diverse group of officer cadets from different backgrounds. Officers who, unlike Virginia police officer Joe Gutierrez shown in a bodycam video harassing, threatening and pepper-spraying Caron Nazario, a Black and Latino Army second Lieutenant, recognize themselves in the people they are protecting.

“There are studies that demonstrate that an officer of color is less likely to use unnecessary force against a civilian of color,” Castro said. He juxtaposes these findings with the issue of training, which as it stands, needs reform for these connections to occur.

“I don’t believe that better training is enough, but can it be helpful in certain instances? Sure. Maybe most importantly though, is the accountability that comes when officers overreach,” Castro said.

Castro believes the core issue is that officers are allowed to act on their biases with impunity and hide behind the shield of qualified immunity.

“To protect Black and Brown communities from a system that routinely undervalues their life, you need much greater accountability,” he said. He said that this means stronger disciplinary measures.

“It means federal withholding of funds for police departments that have bad track records when it comes to disciplining officers, it means the ability to terminate the employment of police officers who show a pattern of this kind of behavior,” he said.

According to Castro and other advocates, a national “use of force” standard would mean that all officers should not use force unless they’ve exhausted all other reasonable means under the circumstances.

That standard would be applied to local law enforcement and include the withholding of federal funds if local jurisdictions choose not to abide by that standard and somebody gets hurt or killed because of it.

As things currently stand, the use of undue force against the public is commonplace.

He dropped out of the Presidential race over a year ago, and since then, Castro has been amplifying candidates and pieces of legislation that share his vision to hold police accountable.

AL DÍA asked if he had plans to fight for reforms from a place of office in the future. Whether he is elected in the future or not, it’s not a mission he plans to let go of.

“Absolutely,” Castro said. “We need to lift up people who have the courage to take on these issues and wherever I am, whether in private life or public life, I’ll try and make a difference by supporting people who will take it on.”

LEAVE A COMMENT: