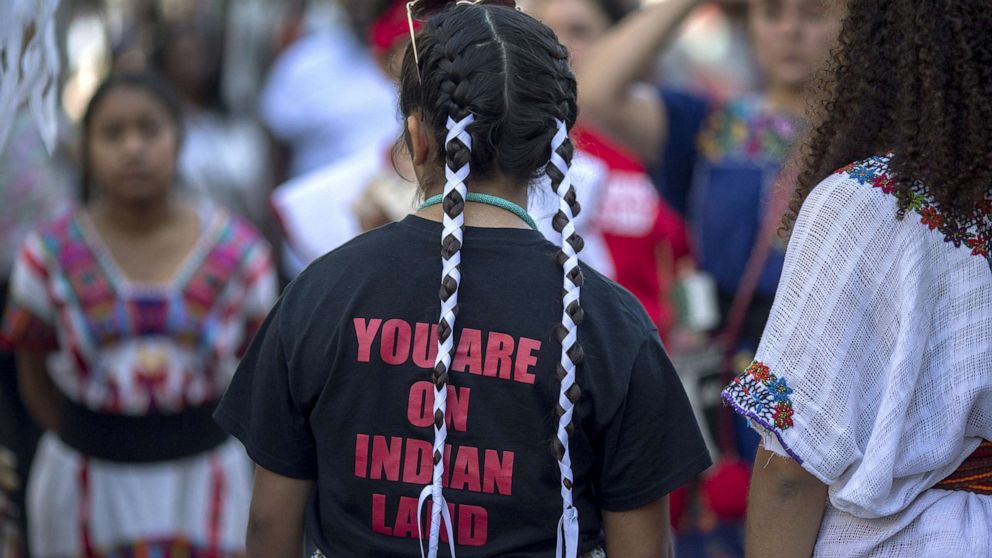

A rundown of some Indigenous People’s Day celebrations across the U.S.

More than 100 cities across the country and a number of states have replaced Columbus Day with the new commemoration of Native Americans.

On Friday, Oct. 8, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation commemorating Indigenous People’s Day, making him the first U.S. president to do so.

In the proclamation, he recognized the contributions Indigenous peoples have made in public service, entrepreneurship, scholarships, the arts and countless other industries.

"Today, we acknowledge the significant sacrifices made by Native peoples to this country — and recognize their many ongoing contributions to our Nation,” the proclamation read.

Biden also marked a change of course from previous administrations by acknowledging the death and destruction of Native American communities after Christopher Columbus journeyed to North America in 1492.

“It is a measure of our greatness as a Nation that we do not seek to bury these shameful episodes of our past — that we face them honestly, we bring them to the light, and we do all we can to address them," Biden wrote.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we honor Tribal Nations and the invaluable contributions of Indigenous peoples. Their wisdom, ingenuity, and leadership in all walks of life has made our country stronger and more prosperous. https://t.co/k2plUzE7bB

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) October 11, 2021

More than 100 cities, including Los Angeles, Denver, Phoenix and Seattle, along with a number of states, including Minnesota, Vermont and Oregon, have replaced the celebration of Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day, deciding instead to recognize the Native Americans that were impacted by genocide after Columbus and other European explorers reached the continent.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters on Friday that the announcement didn’t mean an official end to Columbus Day as a federal holiday, and that for now the day is a recognition of both.

"I know that recognizing today as Indigenous Peoples' Day is something that the President felt strongly about personally, he's happy to be the first president to celebrate and to make it, the history of moving forward,” she said.

In January, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney issued an executive order changing Oct. 11 to Indigenous People’s Day, and on Monday, the city celebrated it officially for the first time.

A ceremony took place at Penn Treaty Park, drawing attendees as far away as South Dakota and Canada. It consisted of traditional music, dances, storytelling and oral histories from Indigenous people around the world.

Happy Indigenous People’s Day! This year, Philadelphia is officially honoring the experiences and legacy of indigenous peoples, as is the nation, via a first-ever presidential proclamation. #IndigenousPeoplesDay

— Senator Nikil Saval (@SenatorSaval) October 11, 2021

This year, organizers wanted to center the Lenni Lenape Indians, native to eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, and their displaced descendants, so they chose Penn Treaty Park, as it was the site of early treaties between the Lenape and Quaker settlers.

For many participants, the event served as an education on local Indigenous people and traditions that they didn’t receive in school or elsewhere.

Tailinh Agoyo, director of We Are the Seeds of CultureTrust, an Indigenous arts organization in Philadelphia, told WHYY that she believes many people have an idea that Indigenous people are “somewhere else,” or “don’t exist at all.”

But according to the U.S. Census Bureau, around 14,000 Philadelphia residents identify as Native American.

“This particular event is really special because … it’s an opportunity for the Philadelphia community to come out and experience indigenous music and dance and talk to indigenous people,” Agoyo said.

RELATED CONTENT

Meanwhile, another U.S. city continued to reckon with their past wrongdoings and work to create a more welcoming and equitable space for Native residents.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, along with Councilmembers Mitch O’Farrell and Kevin de Leon, announced the city’s launch of the “Indigenous LAnd Initiative,” which includes the removal of Father Junipero Serra’s name from a downtown park.

Serra was a Catholic priest from Spain who established California’s mission system and sought to baptize Native Americans. In 2015, his sainthood was protested by Native Americans in the city, who claimed that Indigenous people were brutalized, beaten and forced into labor for his missions.

The park will be called La Plaza Park until a new name is officially adopted. The initiative will rename landmarks, beginning with the park, and it will create an Indigenous Cultural Easement at the park and other locations across the city to give local Indigenous people space to practice traditional ceremonies.

Los Angeles Councilmember O’Farrell, joined by Mayor Garcetti and Native American leaders, marks Indigenous Peoples Day with announcement of 'Indigenous LAnd Initiative' https://t.co/tH4dh96bhQ via @IndianCountry #ICTPressPool

— ICTPressPool (@ICTPressPool) October 12, 2021

“Our indigenous brothers and sisters deserve justice, and today we take a step toward delivering both greater cultural sensitivity and spaces for Angelenos to gather and perform their traditional ceremonies,” Garcetti said.

The Indigenous LAnd Initiative will also seek to rename the Christopher Columbus Transcontinental Highway.

O’Farrell, who is a member of the Wyandotte Nation and only Indigenous member of LA’s City Council, will introduce the renaming process through a resolution.

“For the first time ever, we are putting Native American communities at the center of decision-making on issues related to our history and our future,” O’Farrell said.

California is home to more people of Indigenous heritage than any other state, and LA County is home to more Native American and Alaska Natives than any other county in the nation, totaling around 140,764 people.

All land is Indigenous land.

— Mitch O'Farrell (@MitchOFarrell) October 12, 2021

As Los Angeles’ fourth Indigenous Peoples Day comes to a close, we are lighting up Los Angeles’ skies in honor of the original inhabitants of this land. pic.twitter.com/ZqLYCg3UKW

“These policies have the promise of being truly transformative. We look forward to working with residents and city leaders to build a better future for Native Communities across Los Angeles,” said Rudy Ortega, Jr., Tribal President of the Fernandeno Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.