The trials of Gabriel Fernandez: Who protects abused children in America?

The documentary series Netflix released on Feb. 26 about a 2013 infanticide in Los Angeles examines the cracks in the child protection system.

"Is it normal for mothers to beat their children?"

Teacher Jennifer Garcia opened her eyes wide when her student Gabriel Fernandez, just 8 years old, asked her the question. She wanted to know what he meant. If it's normal to get hit with a belt buckle, he said. If it's normal for you to bleed.

Gabriel had just arrived at the school and it didn't take much for an experienced teacher to deduce that things were not going well at home. She called Child Protective Services in Los Angeles County and the case ended up in the hands of a social worker, who never stuck her nose into the dysfunctional home the boy was part of. If she did, it was in passing, with her eyes averted from the tragedy unfolding in the family.

This was first reported by The Atlantic journalist, Garrett Therolf, in an investigation he conducted in 2018. It happened late, as everything always does. The boy had been dead since May 2013. His mother Pearl Fernandez and her boyfriend had murdered him.

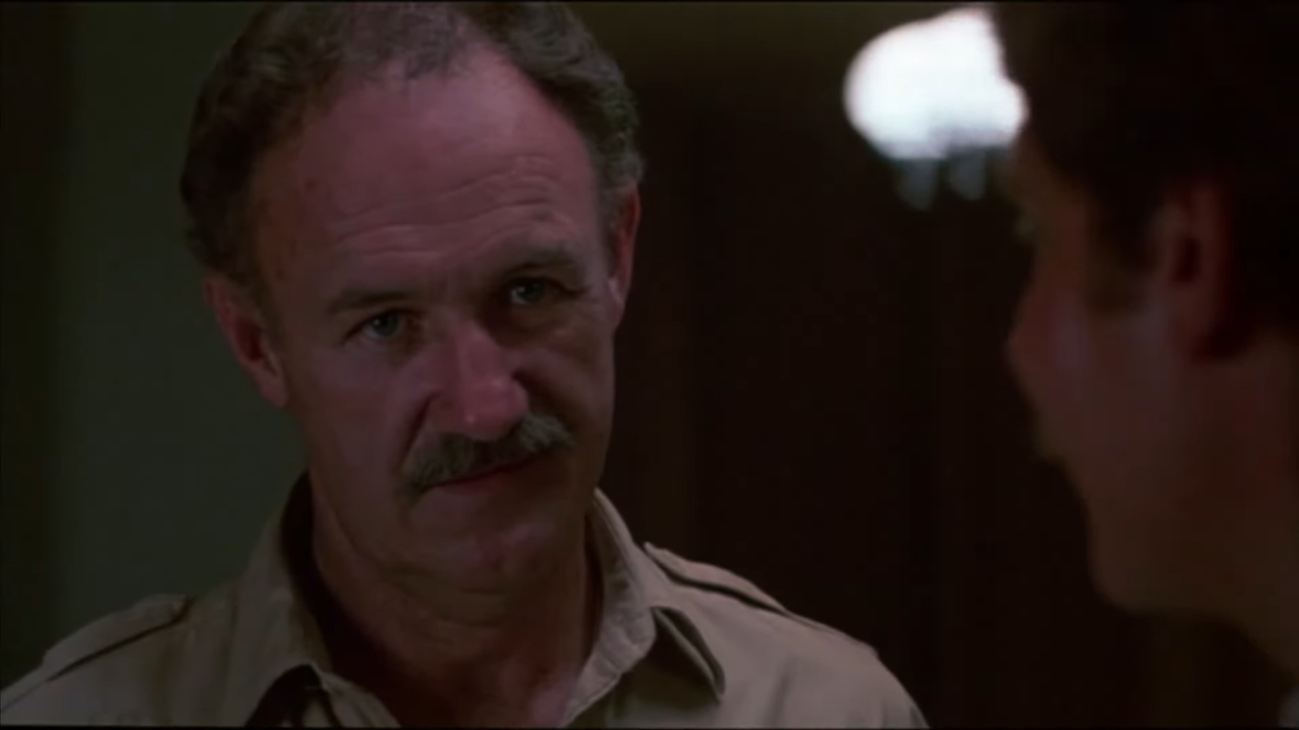

In "The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez", documentary filmmaker Brian Knappenberger takes Therolf's investigations as his starting point and gathers the testimonies of those involved in the chilling case that froze the blood of the Los Angeles to examine how the United States deals with child abuse and prevents it. His work exposes cracks in a system that is supposed to protect the most vulnerable, but fails miserably.

"Nobody listened to Gabriel when he was alive," the director tells TIME. "Many people failed him, and there are many reasons why this happened. But when you get to the end, it's about how you treat children. Or rather, why didn't they intervene to save him?

The facts, which are reviewed in a docu-series released at the end of February on Netflix and ended with death sentences for Gabriel's mother and her partner, are as disconcerting as they are difficult to face.

Nothing happens overnight, everything has a process. Gabriel had been a happy child while living with an uncle, at least that's what the testimonies said. But when his mother Pearl regained custody and moved him and his two siblings in with her and her partner, Isauro Aguirre, in Palmdale, north of Los Angeles, things quickly went south.

The series often cites Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) records, which show case workers being fed false abuse records by Pearl Fernandez and never finding any "anomalies" when following up on multiple occasions after receiving the call from Gabriel's school.

Over time, as Gabriel attended school, the bruises, chapped lips, and locks of torn hair were growing in number, and so were the questions. It all culminated on May 22, when Pearl called 911 to report the death of her youngest son, whom the paramedics found with broken ribs, buckshot in his body and a fractured skull.

His siblings would testify at the trial that they witnessed the humiliation Gabriel suffered at the hands of his parents. How they mistreated them all and called Gabriel "gay" for playing with dolls, or locked him in the closet and forced him to eat cat food.

The prosecution later accused case worker Stefanie Rodriguez and three other colleagues of falsifying public records and child abuse. Her excuse was that she had cases as bad as or worse than Gabriel and his sibling's, and that her and her colleagues were overwhelmed.

For Knappenberger, the story came to life the day he received permission to attend the trials and heard the testimonies of abuse. "It was heartbreaking," he said to TIME. "You realize the amount of pain that's out there."

RELATED CONTENT

The documentary series, according to him, does not attempt to take advantage of the phenomenon of true crime by continuing to exploit the violence and pain of the victims as morbid entertainment, but rather to amplify and analyze "systemic problems" and how violence against children is combated in the United States. It's a system, he says, that often fails because of its lack of transparency.

During the trials, beyond the death sentence of Pearl Fernandez and Aguirre, social workers were treated as co-responsible for the tragedy and for minimizing the evidence. "They received a lot of attention. To some extent justified," says Knappenberger.

But that's not the end of the story. There were clear problems with the system.

According to the latest HHS Administration for Children and Families (ACF) report on child abuse, there has been a decline in child abuse cases in recent years. In 2017, some 3.5 million children were investigated, 674,000 fewer cases than the previous year.

While the figure is still very high, the system is often still so inadequate that outside agencies and contractors must provide also services the government cannot.

How do we protect the most vulnerable? In the face of negligence and lack of public resources, another force is imposed: that of citizen resistance and care.

If you believe that a child in your neighborhood is being abused, contact Childhelp HERE.

LEAVE A COMMENT: