Puerto Rico's Harlem Hellfighters

Afro-Puerto Rican members of the Hellfighters’ band helped define the regiment’s cultural impact on Europe

When considering the contributions of African-Americans to the U.S. armed forces, there are few individuals or groups more renowned than the 369th Infantry Regiment. Also known as the Harlem Hellfighters, it was one of the first predominantly African-American regiments to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I. The troop served under French Command because the U.S. Army refused to recognize it, and spent six months on the front line, losing approximately 1,500 men. Their heroics earned them a regimental Croix de Guerre from the French Army.

But while the regiment’s heroics in the face of discrimination are an integral part of national African-American history, their cultural impact on Europe isn’t as recognized. The Hellfighters’ band, which performed all over France during the regiment’s deployment, is credited for bringing jazz to Europe. Even less known is the Afro-Puerto Rican heritage that many of the regiment’s members also shared and expressed in their time in Europe.

Formed in 1915, the Harlem Hellfighters didn’t include Puerto Ricans until 1917, when the President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones-Shafroth Act in March of that year. The act recognized Puerto Ricans as U.S. citizens, though the island still remained a colony.

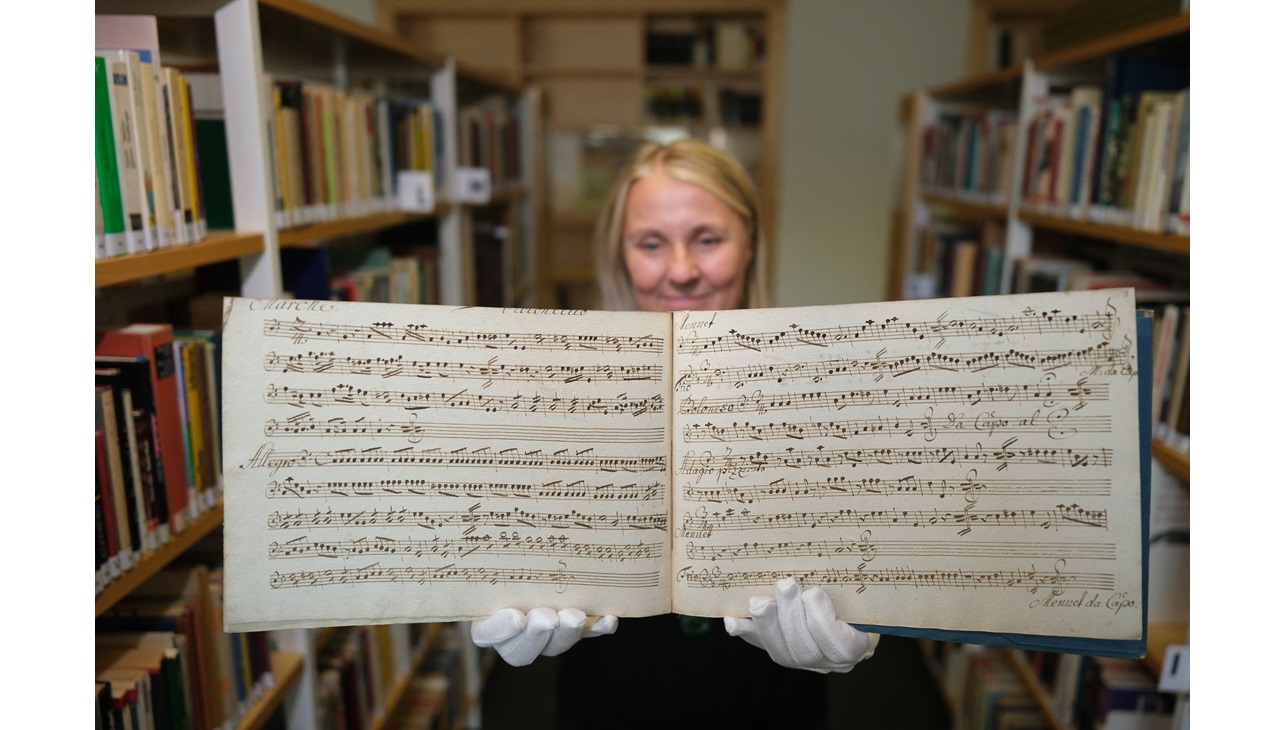

It was around this time that James Reese Europe visited Puerto Rico looking for musical talent. Europe was a star in Harlem’s music scene who signed up for service and received the duty of military band leader in addition to lieutenant.

Of the 44 members of the Hellfighters’ band, 18 were recruited from Puerto Rico. The island was a haven for musical talent, with a tradition of municipal bands that resembled military ones. Puerto Ricans’ unhindered access to instruments also meant they could learn more of a range of instruments,unlike their African-American bandmates, who were subject to Jim Crow laws, which forbid music education and access to more expensive brass instruments.

RELATED CONTENT

One of the Afro-Puerto Ricans recruited by Europe was Rafael Hernández. The now universally-known Puerto Rican composer was 26 at the time, and joined the band alongside his brother. Hernández could play six instruments, had toured Puerto Rico with a circus and played with some of the island’s most well-known artists of the time. Other Afro-Puerto Ricans recruited by Europe who would become successful musicians were Rafael Duchesne Mondríguez and Gregorio Felix.

Once arriving in France in early 1918, the band accompanied the new, African-American faces on the frontlines with its unique sound. Europe’s fellow composer and Hellfighter Noble Sissle provided commentary of the band’s effect on the regiment. From sunup to sundown, the band offered a different sound depending on the time of day.

“In this way, they played a very important part in getting the spirits up,” wrote Sissle.

In all, the band played in 25 French cities during the Hellfighters’ time in France, introducing the population to ragtime and proto-jazz. Sissle recounted how the band caught the ear of the French working class and how no one - including German prisoners of war - could resist tapping their feet to the new music.

“I sometimes think if the Kaiser ever heard a good syncopated melody he would not take himself so seriously,” Sissle is quoted as saying in the Jun. 10, 1918 edition of the St Louis Post Dispatch.

This past Sunday was the 73rd year since the disbandment of the 369th Infantry Regiment. The Harlem Hellfighters left France after WWI as not just war heroes, but also as ambassadors of a newfound American culture. The post World War I Harlem Renaissance was the epitome of that culture, and many Puerto Rican members of the Hellfighters’ band went on to success during its heyday.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.