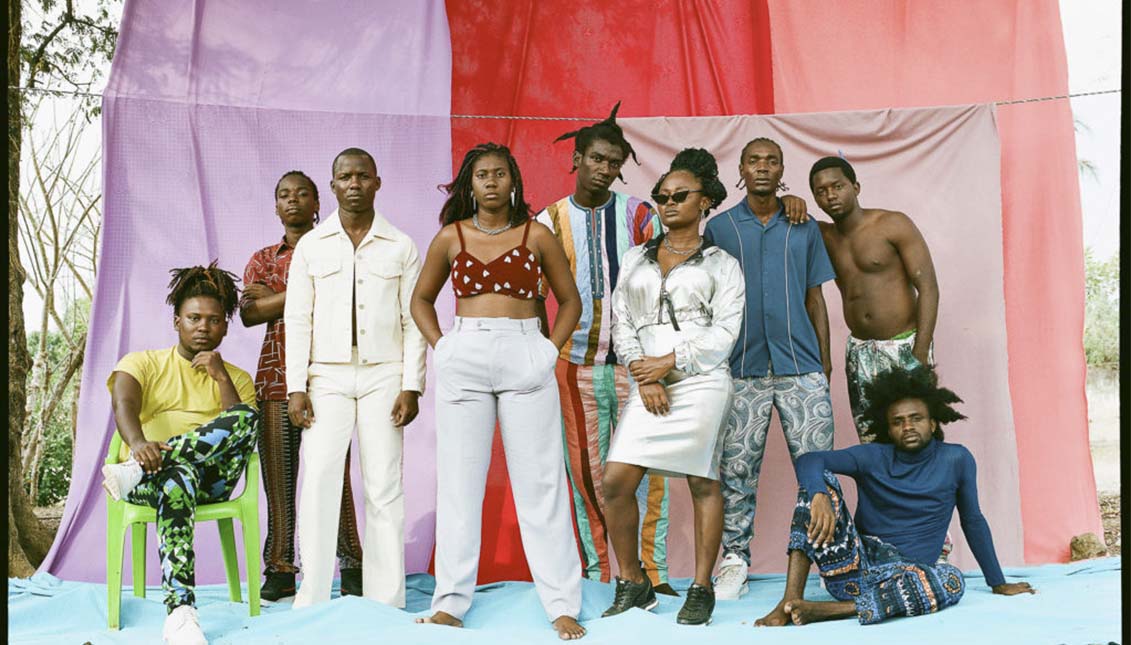

When the ancestors rap: Kombilesa Mi and hip-hop as indigenous resistance

Despite the Elder’s initial fears, the Kombilesa Mi’s “rapped champete” has got the younger generations from Palenque (Colombia) to take pride in their roots.

Two centuries before Colombia had gained independence from Spain, the town of San Basilio de Palenque was free land.

And maybe because of it, they have known how to preserve their culture and African tradition so well that Palenque seems a place where time doesn’t flow in the same way.

Or if it does, it sounds like a rap base. Yeah, a folkloric one.

With a mixture of Spanish and Palenquero, one of the 68 indigenous languages in the country that still resist to the “assimilation” process, the Afro-Colombian hip-hop band Kombilesa Mi (“My friends”, in Palenquero) has become the best guardian to protect and transmit the roots to the new generations.

“At one point, Palenquero was considered poorly spoken Spanish, and because of that, people felt bad and decided not to speak it,” tells to BBC Andris Padilla Julio, aka Afro Netto, the leader of the music band born eight years ago in a town with no more than 3.500 inhabitants, all of them are descendant from the maroon slaves who got free from the slavery at the end of the 16th century.

“If we want people to learn how to say 'Bye', we do it by singing, adding some rhythm, and people enjoy that… With hip-hop, people can dance but they also listen, and since I’m interested in delivering a message and hip-hop allows me to do that and that’s why I love it,” adds Padilla

Beating the drums and singing Palenquero – a mixture of Bantu, Portuguese, Spanish, and French - Kombilesa Mi doesn’t need beats from a computer for them to rap their experiences in Palenque, while keeping their language alive.

With a foot in the urban music and the other in the traditional champeta that sounds in San Basilio and Cartagena’s streets but once it had been associated to “poverty” and “vulgarity”, Kombilesa Mi has made rap “champeteado” a way to pride their roots so as a symbol of cultural resistance.

Their start wasn’t easy, though.

RELATED CONTENT

“In the beginning, the Older people were very suspicious because they felt we weren’t respecting the original spirit of Palenque music and we damaged it by including sounds from the U.S., Venezuela or Cuba,” explained to Vice the band, whose album debut, ‘Así es Palenque’, was released in 2016.

“When they realized we were playing music with the ‘marímbula’, the ‘tambora’, and the ‘maracas' and rapping about Palenque, they got convinced.”

Kombilesa Mi is not the only band to claim their own roots through urban, heavy or rock music and find their communities are reluctant.

The Mexican rappers Slajem K’op o the rockers Sak Tzevul, who sing in Tzotzil, a language from Chiapas (Mexico), caused great agitation when they started to play traditional melodies with “unusual” rhythms.

“My goal was to give the youngsters something new from our culture and say: One day we will be proud of what we feel embarrassed in the present,” stated to BBC Damián Martínez, from Sak Tzevul.

Considered as somewhat “exotic” and “curious” and though they sometimes have to face discrimination, what it is true is these grassroots vibes work as the old stories and legends told by the Elderly to the young people meanwhile they seated around a fire.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.