An unknown treasure of American history

A 225-year-old document exhibition aims to reveal details of national history hitherto unknown to most Americans.

Did you know that during the drafting process of the United States Constitution, five men were responsible for putting into one text the ideas that founded the creation of a new nation? Do you know how many times the text was written before it became the Constitution of the United States of America?

Do you know how the process was and how much time has passed since the first letter was written until the publication of the final text that gave life to a new form of government? Do you think that process was without conflicts and differences?

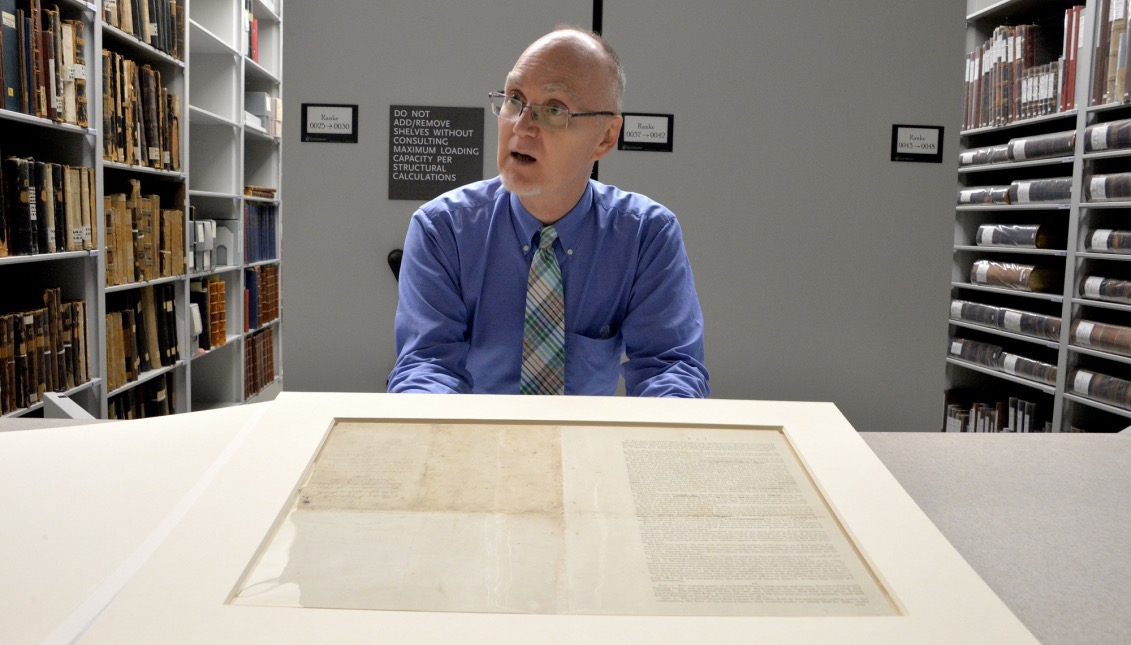

These and other questions find their answers in a labyrinth of vaults where documents of more than 225 years old are jealously preserved by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) and that from next May 4 - in alliance with the National Constitution Center - will be known by the public of the city in what promises to be one of the most interesting exhibitions of this 2017.

Under the name of American Treasures: Documenting the Nation's Founding the HSP and the National Constitution Center set out to uncover unknown aspects of the nation's founding in the summer of 1787, through the first exhibition of this type of documents in 50 years, which - in the words of Charles Cullen, president and CEO of HSP – “will provide new insights into the way we have interpreted the process in which our Constitution became what it is today".

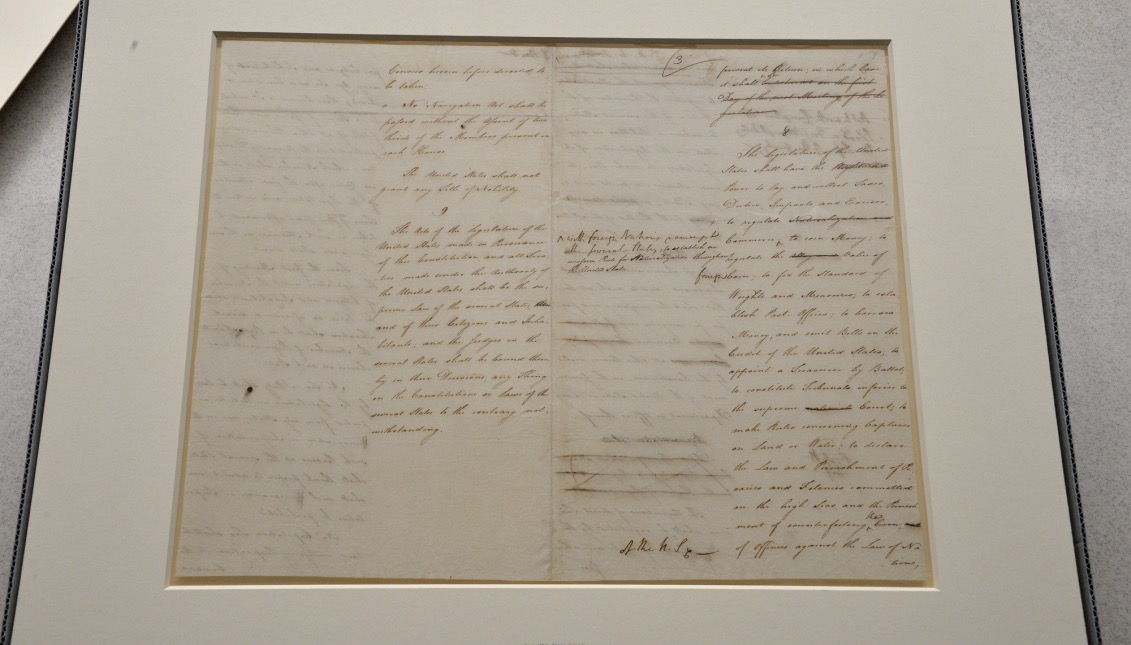

And it’s no surprise, since it’s a series of documents (the first four drafts and the first official printed copy of the final text) that speak of a bidding process between the different confederate states that then held a difficult debate on how to form a new government without putting at risk the newly acquired freedom.

This conclusion comes after a glance at the first attempt at freehand writing and excellent calligraphy by Pennsylvania’s attorney and representative at the Constitutional Convention, James Wilson.

The first draft reads “we the people of the states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts…” as if the new homeland was still a kind of summation, state by state, of particular societies that were then united with distrust to the nascent State.

For Lee Arnold, senior director of the HSP library, this difference with the final text represents far more than it seems. According to the guardian of this collection, "it is not insignificant that they went from making a list of the 13 states of the union to saying "we, the people of the United States", because that means they had a change of heart: they recognized the need to cease to be seen as independent states and to be seen as a union. That's very significant, it's not just a cosmetic change".

RELATED CONTENT

Another difference is in the name of the country. Before the final Constitution, the first idea was to call United People and States of America. That changed in the second draft. Ideas such as including the payment method of senators and representatives as well as freedom of expression, although discussed and recorded, were discarded in the final text.

On the importance of this exhibition, Cullen says that there has never been one that focuses on the process of drafting the Constitution, "there have been many about the Constitution, but no one has tried to reveal the process of its elaboration."

And this is because the drafts also shed light on how all the ideas - and differences - were then approved through the work of the Committee of Detail, the one in charge of putting in a single text everything discussed and agreed in the Convention of Philadelphia.

"When the drafts are read, almost all written by Wilson, the first impression is that perhaps were his ideas - we do not know if he wrote them alone or with someone else - but if you take these documents (no one had access until almost 1880), if you read the notes of the debates that followed the work of the committee, and the notes of the people who were in it, you can see the roles played by each member of the committee and where they came with the proposals that ended up included in the Constitution", he continues.

The drafts of the Constitution, although they have no legal effect, constitute a kind of compass that guides the spectator on a trip 225 years ago to be part of the national history and imagine the heated discussions and extensive hours of work preliminary to the birth of the country.

As Cullen puts it, "you can read our constitution today and see what there is, but to really understand what it means, it is very helpful to see what these drafts say: principles, ideas of separating powers, maintaining balance, The interests of the people and that the country belongs to the people ... all that was recorded there. "

The exhibit will take place at the National Constitution Center starting next May 4.

LEAVE A COMMENT: