Rooftops in Brazil's favelas are a paradise for quarantined residents

Those who telework on the roof feel privileged. However, downstairs, in the streets, a very different story is told.

Typical places for barbecues and sunbathing, the rooftops of Rio de Janeiro's favelas are being reinvented as spaces for essential uses in times of coronavirus quarantine.

From the rooftops of three- and four-story buildings in favelas such as Vidigal - one of the most visited in Brazil - families gaze in the distance at the statue of Christ the Redeemer and the coast of the Leme neighborhood's residential area as they rush to set up their offices outside.

Isolated from the world, confined to their homes by the pandemic, the neighbors are trying to make the quarantine more bearable and have turned these spots into coworkings and even gyms.

The phenomenon, reported Brazilian journalist Geraldo Ribeiro, has spread to many other communities in a city used to living on the streets and beaches.

"People can't go out, but even at home we need to stay active and connected to the world, so we end up going to the roof," a resident of Vidigal, William de Paula Lucas, aka "Ninho," who transformed his roof into an office and a space for practicing capoeira, explained to Ribeiro.

The physical education teacher lives alone on the top floor of the building and from there, with a mobile phone and laptop, he holds video conferences, teaches, and helps families in the area who need food and medicine.

His neighbor, Liviete Alves da Silva, is desperate to go to the beach and is not satisfied with seeing it from the window. Her grandniece, Eduarda, only 7, found a way to make Liviete happy and turned the rooftop into a makeshift pool.

A little further away, in Ladeira dos Tabajaras, Botafogo, Raylton Moreira dos Santos has set up a jiu-jitsu gym on the roof that he shares with his wife, Renata, who follows her online law classes from the heights.

"Now, whoever has a roof in the community is the king," said Santos.

Isolation and social distance are hard on Brazilians, people who love meetings and parties. However, the buildings in the favelas are so close together that the neighbors take advantage of the opportunity to chat from the rooftops, and even to start making music.

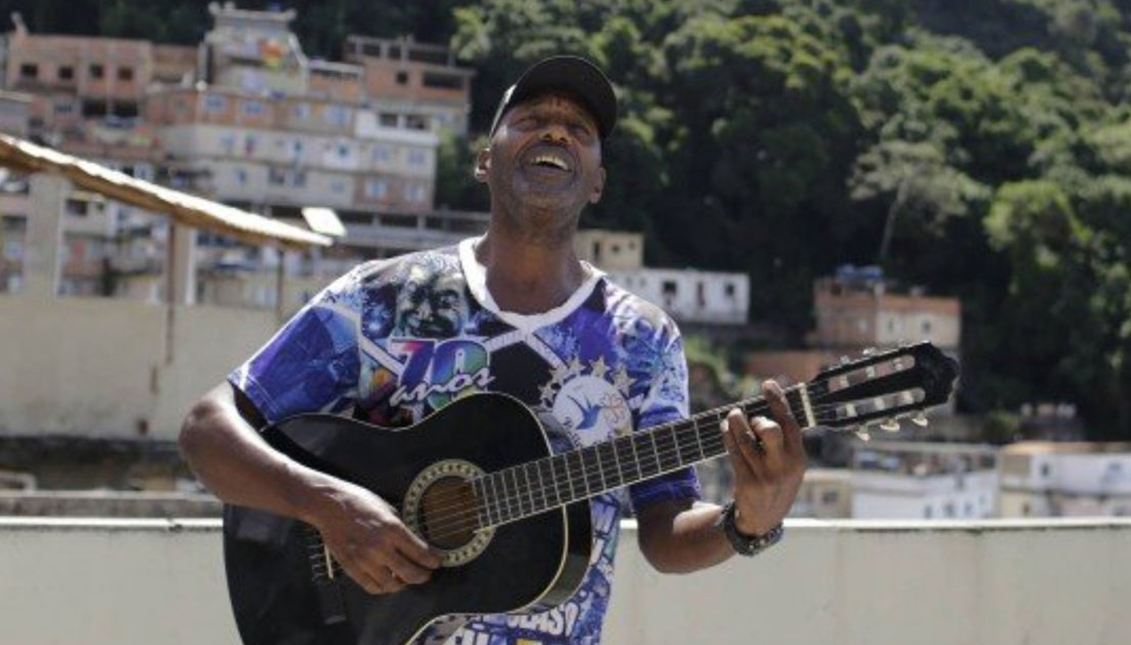

Like Carlo Augusto Jacob, a bricklayer and amateur guitarist, who, every time he goes out to play on his rooftop, gathers a group of neighbors who clap and dance along from theirs.

"At night I come here to play the guitar. Sometimes I join the people from the other roofs to listen and applaud. I play everything from samba to forró, but what I really like is the gospel music", he said, adding that many very religious families also use the rooftops to pray because they cannot go to church.

Down below, in the twisting streets of favelas like Santa Marta, life is not as peaceful as it is up above.

Neighbors are restless and hungry; always wondering how they will feed their families when the last supplies run out. It's even more so in a country hard-hit by the new coronavirus whose president has accepted the death of the most vulnerable as little more than a "payment", or "collateral damage" of this pandemic.

RELATED CONTENT

The desolation has also reached, and is stronger, in other Brazilian regions where a majority of the inhabitants live in favelas.

"It's the most extreme poverty," musician and biomedical expert Renato Rosas, from the Amazonian city of Belém, told The Guardian.

Rosas talked about the Baixadas das Estrada Nova Jurunas neighborhood, where the water is highly contaminated, there are floods, and snakes lurk among the floating piles of garbage, just as drug gangs lurk.

In March, businesses and shops closed, but so did schools, where most children in the favelas ate. Without income and locked up in the houses, there was no way to feed the children.

In response, Rosas and his friends made a plan.

Farofa Black is a music and education project led by him and other musicians and educators, who began raising money to distribute food baskets in the community.

"When we stop at one of these places, people come running. It's very fast, it's all over very quickly," he said.

But they're not the only ones who do it. Activists and social organizations deliver food and hygiene kits to desperate slum dwellers in places like São Paulo, Belém, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Manaus, Belo Horizonte and São Luís.

Their biggest concern is what will happen in the alleys and houses where entire families are crammed together without basic hygiene or adequate health services. These are places where Zika and tuberculosis have thrived and COVID-19 is carving its own space.

With more than 1,000 deaths and 23,830 cases recorded as of April 15, Brazil remains the Latin American country with the highest number of victims, followed by Peru and Chile.

LEAVE A COMMENT: