The Church That Houses the Latent Heart of the Chicano Movement in L.A.

The Church of the Epiphany was the headquarters of La Raza newspaper and the epicenter of the civil struggles of the 1960s. Today, it is also a monument.

Writers like the British Ian Sinclair have made the walk an exercise in psychogeography; that is, walking through a place knowing the history of that place totally changes our perception of the space. It literally immerses us in history. Or begins to immerse us...

From the more than 86,000 landmarks recognized by the National Register of Historic Places, only 8% are associated with African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and other minorities.

Specifically, in the city of Los Angeles, just 10% of sites associated with women, BIPOC, or LGBTQ communities have become landmarks.

Last January, the National Register, in another effort to rewrite history and its imprint to make it everyone's, added the iconic Church of the Epiphany in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles to the list.

The church, which was built in 1887, became in the 1960s the epicenter of the Chicano Movement and a refuge and space for the civil rights struggle and is still a pillar for the community today, half a century later.

"I cried because I needed a place as a Chicana and a place as a Christian to call home," Angelina Lydia Lopez recalls the first time she visited Church of the Epiphany in 1968.

Lopez was demonstrating on a picket line supporting Mexican American activist Sal Castro when recently deceased UCLA professor Juan Gomez-Quiñones told Lydia about a party being held at the parish.

With its high ceilings and religious emblems, the interior was decorated with papel picado, and music from a mariachi band enveloped the attendees.

It was the first time, said Lopez, who had grown up in a Baptist church, that she saw her identity reflected in a place of worship.

Everything about the Church of the Epiphany harkens back to the golden years of La Raza; its basement, now being remodeled into an activity room, was the birthplace of the La Raza newspaper, led by Ramses Noriega and Rosalio Muñoz, the main organizers of the first Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War.

RELATED CONTENT

The Epiphany was also the site chosen by activists during Robert F. Kennedy's presidential campaign and the rallying point for organizing student walkouts to protest inequalities in East Los Angeles schools.

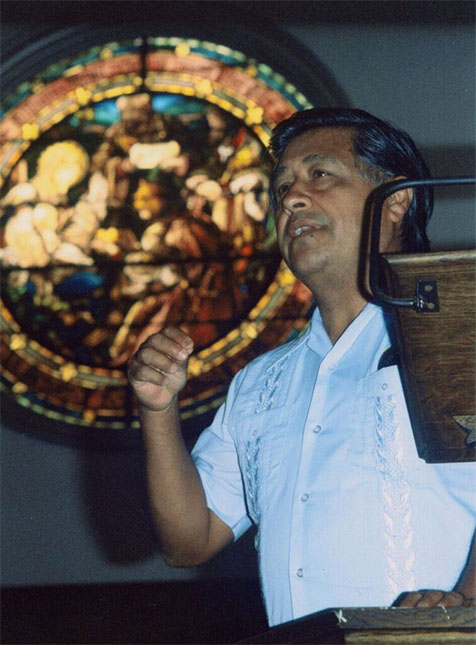

Activist and farmworker movement leader Cesar Chavez took the pulpit and preached for social justice in that very spot, and, years later, the parish served as a refuge for Central American immigrants fleeing violence in their countries.

"That's the legacy of the church," its vicar, Father Tom Carey, told the LA Times. "It's a place where people have expressed themselves."

In fact, Epiphany was among the few temples that became a true supporter of the struggle for equality at a time when Latino Catholics complained about the Catholic Church's lack of involvement in minority causes.

With notorious clashes such as that of Catholics for La Raza at the neighboring St. Basil's Church in 1969, where one Christmas Eve the police had to mediate, Cardinal James Francis McIntyre tried to close the doors in the noses of the angry congregation.

The parish has kept holding its bilingual services during the pandemic, albeit virtually. Meanwhile, it attends to local families in need of food and joins protests and calls for small business owners' relief.

All this, while it undertakes a remodeling process thanks to a crowdfunding campaign launched after learning its conversion to a historical monument in the country.

What makes a place sacred "is what has happened there in the past," concludes Father Carey. "What continues to happen there."

LEAVE A COMMENT: