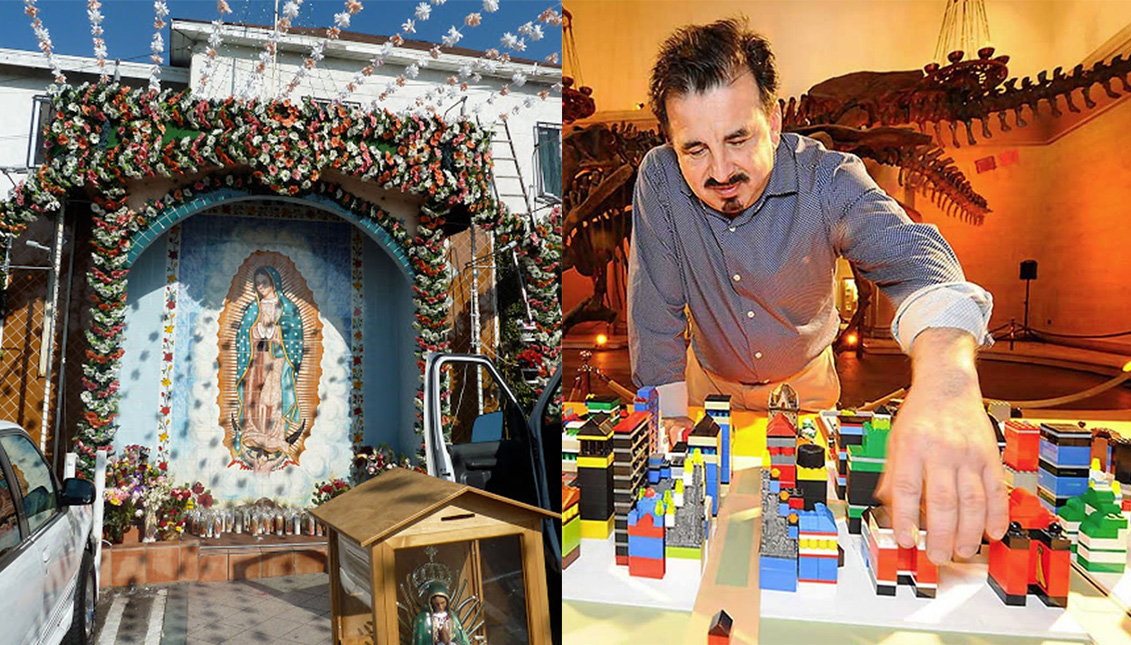

Latino Urbanism: Architect James Rojas' Dream Utopia for L.A.

Ecology, creative freedom and Chicano traditions are part of an urban planning philosophy that puts the community at the center of the debate about the future…

Legos, colored paper or palettes of ice cream. In the unusual workshops of visionary Latino architect James Rojas, community members become urban planners, transforming everyday objects and memories into placards, streets and avenues of a city they would like to live in.

A much more welcoming one, where citizens don't have to adapt to the asphalt and bustle, but is made to fit the people.

Their dream utopia is called Latino Urbanism and is based on finding new formulas for social cohesion through movement and architecture. It's based on the homes of Latinos, especially Chicanos in East L.A., and the way they celebrate quinceañeras in their backyards and reinvent space with the so-called "rasquache" — the art of decorating with reused or discarded objects, such as broken plates or wires. The practice could be a bridge to rethinking the way we move globally.

Homemade arcades, garden sanctuaries, and a decoration that expresses who we are and makes walking, as the architect once said: "a visual, spatial and sensory explosion based on memory, needs and aspirations."

It's the opposite of crazy driving, says James Rojas, who has been without a car of his own for many years, and is convinced that "architects are no longer builders but healers."

"They have to come down from their computers and cars to heal the social, physical, and environmental aspects of our landscape," he said at Woodbury University.

It's something he has been meditating on all his life, made his social crusade, and is at the core of his studio 'Place it! Interactive Planning,' where he leads workshops and talks aimed at involving the community in re-imagining the spaces.

But what are the keys to the so-called Latino Urbanism?

In a conference held last year 2019 at East Los Angeles College, he summarized his vision:

RELATED CONTENT

"Sensory, Economic, Cultural and Social Preservation, Rasquache-Improvised, Making Art and Serving Memory, Needs and Aspirations."

"While transportation engineers are obsessed with time, speed and destination, Latino DIY or 'scratch' mobility interventions are focused on the moment or the journey," said Rojas.

It began in Boyle Heights, East L.A., a place that fed his imagination for more than three decades, when he wrote his master's thesis at MIT in the late 1980s. Long before, he was walking the streets of his childhood, while remembering the difference between the houses on his block and the perfect lawns of Montobello.

"Lawns were the way Americans became team players," he noted.

Determined to change East L.A., he realized that it is impossible to drive change without spontaneity and creative freedom, which were very close to his roots. The "rasquache" — which is a somewhat derogatory word in Mexico — was to be his spearhead, and be used in multiple performances and installations throughout L.A.'s neighborhoods and beyond.

It is no coincidence that someone like James Rojas forged a new idea of sustainable architecture in Los Angeles, which has been a kind of modern utopia since the 1970s. It's just as Mexican-Americans were advancing positions as a cultural, political and social force especially in the eastern part of the city — the center of the Chicano Movement.

Late 1960s Latino architects such as Frank Villalobos, Raúl Escobedo, David Angelo, and Manual Orozco had already launched a community design space called Barrio Planners and materialized their own Chicano utopia with designs like El Mercadito — based in a market in Guadalajara, Mexico.

They understood, as Rojas, heir to those early artists and designers, that "what architects build is not a finished product but a part of a city's changing ecosystem."

LEAVE A COMMENT: