The internationalist dream of John Willis Menard, the first African-American U.S. congressman

A Creole and an abolitionist, Menard thought that the only chance for blacks to live in freedom was to colonise Latin America, but he later realized that the…

Lincoln thought that even if the abolitionist North won the Civil War, African Americans would never live in freedom.

"You and we are different races," Lincoln told a black delegation invited to the White House in August 1862. "Even when you are no longer slaves, you are still far from being on an equal footing with the white race. Therefore, it is better for both of you to be separated".

The scene may seem astonishing today, but the reality is that some representatives of abolitionism were quite in agreement with him - in 1860 some 4 million people were living in slavery in the United States, 13% of the population. What would happen to them when they were freed, they thought.

These African American leaders began to see Latin America as a place where they could settle, understanding that white supremacy was going to be an eternal blight on the country, as historian Paul Ortiz, author of Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920, acknowledged.

"Several African-American leaders saw colonization to Central America, Mexico or Africa as the only viable solution before the Civil War," Ortiz said.

Among them was John Willis Menard, a young, college-educated Creole activist who in July 1863, months after Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, sailed from New York to Belize, then British Honduras, as a representative of the free United States in search of a place to resettle "freed" African Americans.

Later that autumn, both Lincoln and Menard would realize that expatriating their black citizens was immoral and that everyone should fight for the Union at home, but by 1860 some 11,000 black people had left the United States for Africa in a colonization scheme that had many critics among African-Americans.

"(Frederick) Douglass pointed out that blacks had not caused the war; slavery had. The real task of a statesman was not to condescend to blacks by deciding what was 'best' for them, but to allow them to be free," wrote historian Eric Foner in The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.

The trip to Central America, however, changed the mind of the young John Willis Menard, who began to see the struggle against oppression of African Americans and Latin Americans as a kind of "sisterhood".

And not only that. He went from pushing for black resettlement in Liberia, Africa, and sending a favorable report to Lincoln on the best places to settle in British Honduras to rethinking the need to direct his energy to improving the life of Black people in the United States.

His doubts were finally dispelled by the Union victory in 1865 and the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. By then, Menard had settled in New Orleans and was fighting for equality and black representation in politics and education, briefly taking the seat of another white congressman, James Mann, who had died five weeks.

RELATED CONTENT

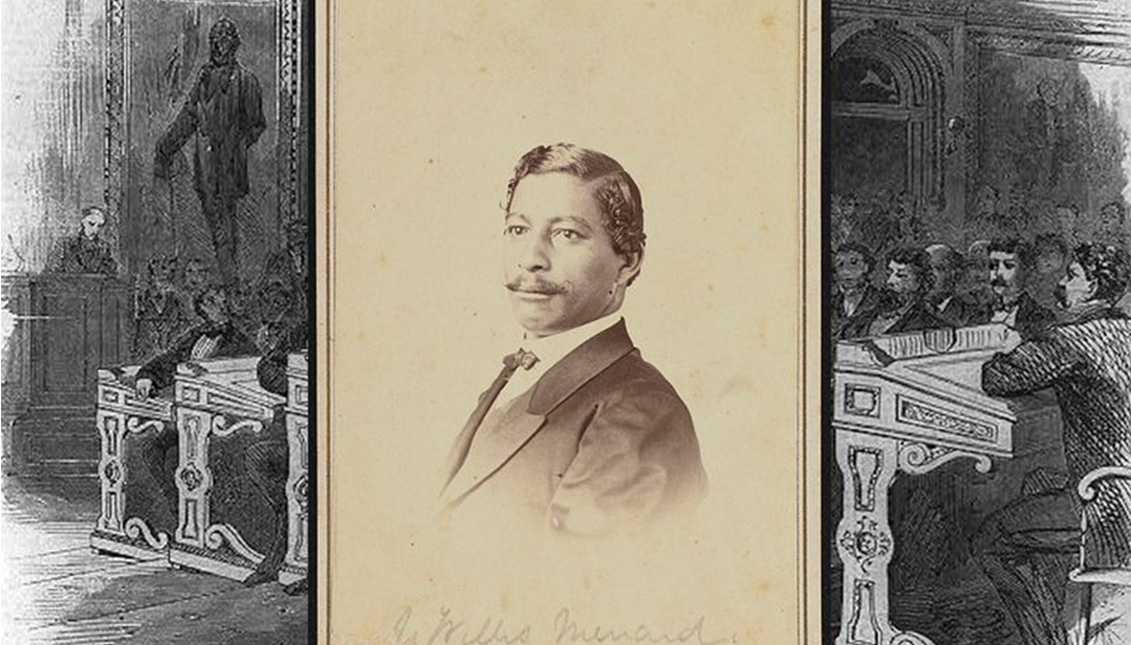

John Willis Menard finally did it, making history as the first African American to be elected to Congress with a landslide majority. However, his opponent, Caleb Hunt, challenged the result.

Then Menard made history again: Congress had to hear a black man address them in the House of Representatives for the first time in 1869:

"I have been sent here by the votes of nearly nine thousand electors, and I should be demure about the duty imposed upon me if I did not stand up for your rights in this chamber," Menard declared.

Unfortunately, the Republican majority washed its hands of the matter, claiming that it was impossible for them to verify the votes.

A few years later, in 1871, and influenced by his experience in Central America, Menard moved to Florida and began writing about the work of immigrants and African Americans in the struggle for democracy at the local level, editing newspapers and eventually moving to Key West to participate in a community with utopian overtones.

For then Key West exemplified the dream Menard sought, with an island community of working whites and Caribbean immigrants. "Part of his genius was that he understood that the freedom of African-Americans in the United States was connected to those freedom struggles in Cuba and Central America," said Paul Ortiz.

The Creole activist also wrote about political events in English and Spanish and became the symbol of a new political outlook that saw freedom and equality in an internationalist way, beyond race and language - indeed, at the time several states passed laws allowing foreigners to register to vote if they became citizens.

Sadly, John Willis Menard's internationalism could do nothing about the wave of violence and supremacy that followed the Reconstruction era and the emergence of groups like the White League that lynched African-Americans in massacres and bloodshed across the South. The terrible ancestors of the KKK.

Today, John Willis Menard is one of the unknown faces in the history of abolitionism, but he was a visionary and laid the foundations for the joint struggles of the BIPOC communities.

LEAVE A COMMENT: