Eyes on the Capitol

In the artworks of Michelle Ortiz, the mothers of Berks stare down PA politicians to demand an end to the imprisonment of children and their families at the…

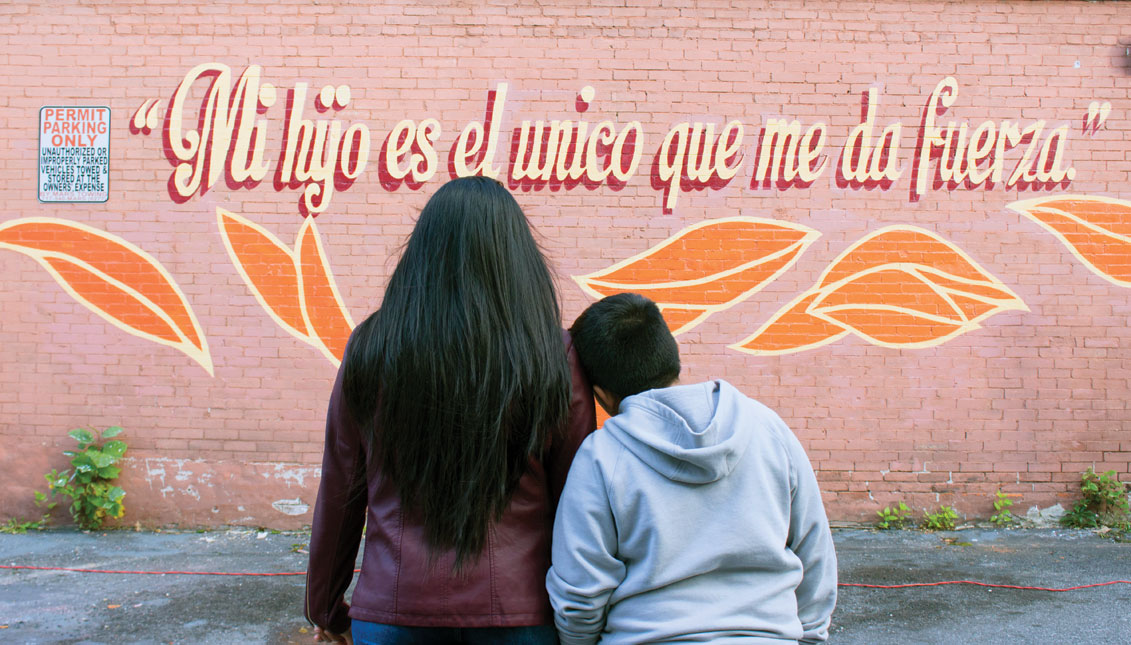

Delmy stood at the wall with her son, reading her own words displayed on the brick wall before her in a small parking lot: “Mi hijo es el único que me da fuerza.” My son is my only strength.

She was before the mural that depicts her own story as one of the mothers who was detained with her children at what is officially known as the Berks County Residential Center in Leesport, PA. The bold, bright image of a mother’s eyes and her and her son's silhouettes that overlooks the parking lot of a bank in the immigrant community of Allison Hill, Harrisburg, is part of the second installation of artist Michelle Angela Ortiz’s project, "Familias Separadas."

That day, Nov. 3, as Delmy stood before the wall in the midst of the crowd gathered by the Shut Down Berks Coalition and other advocacy organizations, echoing the calls for action and witnessing the response to her own story, she tapped into another source of strength: that of sharing her story to support those working to shut down the family detention center for good, and urging recently re-elected Governor Tom Wolf to do so.

“It felt good to support them because when I was in the prison there were many people who were coming to support us. To be outside now, free, to be able to go out, to be able to support them, I feel happy,” said Delmy, whose real name is withheld to protect her security, as she is still residing within the country and fighting her case for asylum. “And I feel strong.”

The installation, which was on display in Harrisburg Oct. 26 - Nov. 18, included images and quotes from extensive interviews with the mothers and their children who had been detained at Berks. Ortiz transformed these into artwork on several 40-foot billboards and bus shelters, an 88-foot long painted image on the Capitol steps, and the 35-foot mural in Allison Hill.

Though Delmy has now been free from detention for over a year, the nearly two years spent under watch at Berks — not sleeping well with regular check-ups throughout the night, imprisoned at the facility — is still not far from her mind, or that of her son’s, who was only 5-7 years old when he was detained. But those memories have now become her weapon in a fight to ensure that others are not forced to continue enduring what she did.

“People like to say, ‘give voice,’ and I don’t really like that term because the mothers have their own voices, and they’re powerful, resilient women who have been obviously victims of the system, but who have pushed forth,” Ortiz noted, lighting up as she spoke about how sending the mothers WhatsApp images of the progress of the installation would often keep her going through the cold, stressful nights before the mural and accompanying installments were completed.

Perhaps the most striking part of the Harrisburg phase of "Familias Separadas" - and no doubt the most controversial, judging by the reaction of at least one of the state senators - was the installation on the State Capitol steps depicting the eyes of Karen and her son, both of whom were detained at Berks, and later deported to El Salvador.

Though that part of the installation was taken down Nov. 10, Karen’s eyes, depicted in striking, vibrant colors spread across the austere marble of the State Capitol, will not soon fade from public memory — or so Ortiz hopes, knowing as she does that the question they’re asking will not lose its relevance anytime soon. The impact of placing Karen's eyes in a place where they would directly confront lawmakers is undeniable. In Ortiz’s words: “You really can’t ignore them.”

The artist said that, in a way that is both “poetic and powerful,” the installation of Karen which confronted state lawmakers, along with the other pieces of "Familias Separadas," provide a “connection to humanity that’s necessary within the narrative of immigration” - a connection which, Ortiz admits, is all too often missing.

Born to immigrant parents and raised in Philadelphia, Ortiz lives a few blocks from where she grew up, in what is known as the Italian Market area (though it includes more people than Italians, she noted in our conversation). Her studio is also nearby, where she has committed herself to large-scale works that engage collaborative storytelling and spur community-based action, which have been nationally recognized and supported in part by major grants and fellowships such as the Rauschenberg Artist as Activist Fellowship.

In the process of creating both the first installation of "Familias Separadas" in Philadelphia and "Flores de Libertad," a striking paper flower display put up outside of Philadelphia’s City Hall in 2015, and in doing the interviews and preparation for the second phase of the "Familias Separadas" project in Harrisburg, Ortiz said she has tried to focus not just on the mothers’ current situations and experiences in detention, but also their lives prior to detention and their future dreams to ensure that “they have moments to remember where their strength comes from.”

For many, like Delmy, that strength is their children, and their love for them.

“I feel like people just don’t really place that value on love, but love is the driving force of thousands of people right now crossing borders,” said Ortiz, referring also to the asylum seekers who have been part of the “caravans” of migrants.

“The mothers that have made that very same journey, that have crossed many borders and then arrived to our country and upon arrival they’re now incarcerated and have to deal with all these other obstacles and trauma,” said Ortiz. “But I feel that the reminder needs to be the ‘why,’ right? And not the, ‘Oh they’re coming, and what are we going to do.’”

The question still remains, for Ortiz and others, of how to tell a story that is more comprehensive, more complex than that “what” of immigration. But that of the “what” to do in response to Central American immigrants arriving in the U.S. has found an unlikely precedent in a setting far from the desert landscape of the border, in a facility nestled in the green, rolling hills just outside the modest city of Reading, Pennsylvania.

The Berks County Residential Center first became a detention center for immigrant families and children in 2014. In early 2016, the PA Department of Human Services revoked its license due to a number of violations, including a sexual assault case. The county then appealed this revocation of the license.

Almost three years later, the case is still mired in what lawyer and advocate David Bennion refers to as an “impenetrable administrative quagmire” as it is being adjudicated by an administrative judge from within the Department of Human Services.

Governor Wolf could take action, according to Bennion, the Shut Down Berks Coalition, and others, though the governor has said before in statements that his hands are tied and the matter is under federal jurisdiction since the center is run under a federal contract.

RELATED CONTENT

“If the governor instructed the Department of Human Services, [and said]...it’s important to the people of the Commonwealth that all children — not just citizen children, immigrant children as well — be kept safe from harm and not be psychologically tortured in prison, then he could instruct the Department of Human Services to issue the Emergency Removal Order,” said Bennion, whose organization, Free Migration Project, is part of the Shut Down Berks Coalition, and is also one of several legal entities that have sought to intervene in favor of revoking the license.

Bennion said that issuing an Emergency Removal Order to close the center would be significant for immigration policy at the national level because “ICE has been relying on Pennsylvania’s license to justify the entire national family detention program.” He noted that Berks has often been used as “overflow,” such that when a family was detained for 20 days in Texas, they would be transferred to Berks to prolong their detainment under the Flores Agreement, which stipulates that children can only be detained in facilities that are both licensed and non-secure (those detained are free to come and go). However, though Berks was licensed prior to 2016, it was always a secure facility where those detained there were unable to enter and exit at will, and therefore in violation of the Flores Agreement even before its license was revoked..

The use of shelters as detention centers is spreading, Ortiz noted, as is exemplified by the opening of the VisionQuest shelter in North Philadelphia, which plans to house up to 60 undocumented children.

Ortiz said she hopes the stories told in "Familias Separadas," depicting the long-lasting effects and trauma of detention, continue to “[remind] folks that this is happening in our state, and that it’s not just a border issue.”

By issuing an Emergency Removal Order, Ortiz said that Wolf “has that opportunity to demonstrate to the rest of the nation and this current administration of what it means to create a system that gives dignity and respect to people that are seeking safety.”

Ortiz is planning to release a short documentary in the spring/summer of 2019 with the stories of the mothers, as well as a book that would be available at community screenings of the documentary Ortiz will organize throughout the state.

In partnering with the Shut Down Berks Coalition, MILPA, and other advocacy organizations, Ortiz said that the goal of her work is not just to have people “connect and empathize.”

“If it stirs empathy, if it stirs sadness, ...[I] can say, ‘Well, if you have all of these emotions this is how you can place them,’” she added.

The artist, who is herself a mother of a young child, said moments like that of one video clip she recorded, where a formerly detained mother sings to her child who is frightened and reluctant to go outside of one room since they were released from the detention center, are what still move her to do the work that she does.

“In the midst of all of this fear and attacks and people trying to strip away their humanity, they still find a moment to give a sense of security to their child, to say that everything will be okay,” said Ortiz. “Those are the moments of that connection to humanity and the ‘why.’”

LEAVE A COMMENT: