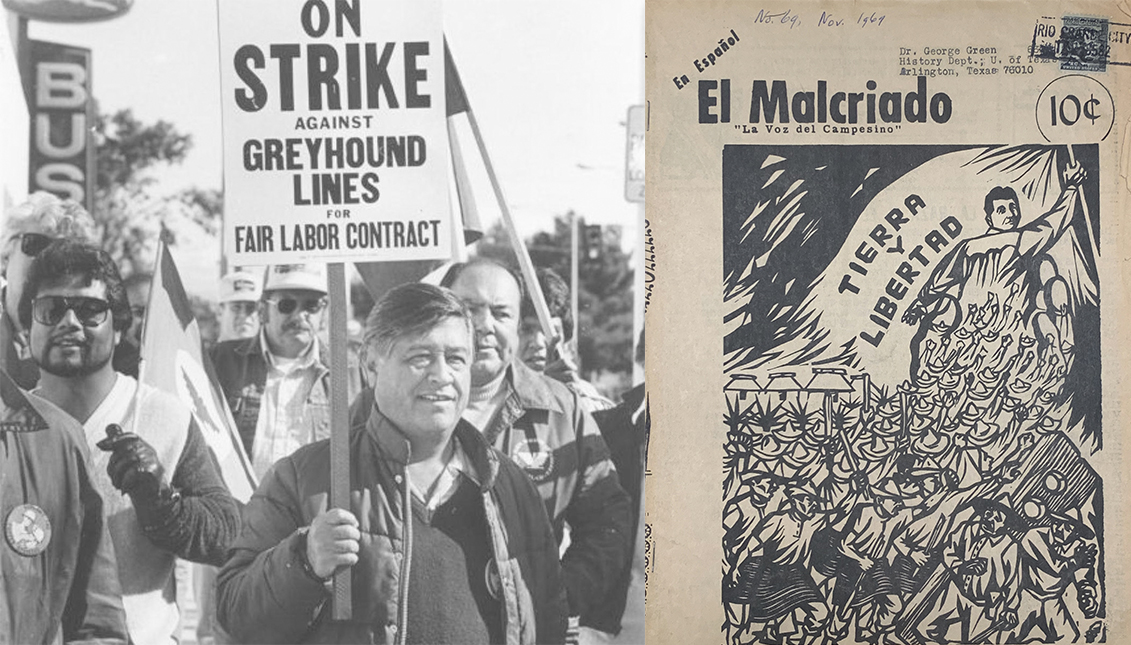

El Malcriado, the newspaper that became emblematic of the Chicano labor struggle

Run and written by migrant workers, this newspaper was dedicated to denouncing the abusive working conditions suffered by migrants in the 1960s and 1970s.

Before newspapers like La Raza appeared and new generations of Chicano activists took up the baton to demand a dignified and egalitarian life for Mexican Americans, the Latinx leaders of the 1960s paved the way for the revolution by highlighting the precarious wages and abusive conditions experienced by farmworkers.

Names such as United Farm Workers leader Cesar Chavez and activists Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla played remarkable roles in a turbulent decade, especially in California. The National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) also saw the light of day.

Rallies, marches, and strikes marked the common effort to demand respect for day laborers. However, something was missing... A printed voice.

A howl that would be read and allow its protagonists to reflect in a more leisurely way on all the issues that were oppressing them and needed urgent change.

This is how Cesar Chavez came up with the idea that created El Malcriado, a legendary newspaper that was first published in 1964 and would end up as the printed but unofficial voice of the United Farm Workers until 1976. It also became a way to politically organize the movement in both English and Spanish.

Since Chavez and Bill Escher — its first editor — were admirers of Mexican revolutionary art, they were inspired by another newspaper published during the Revolution. They also included revolutionary artwork in their pages, along with political commentary, coverage of labor issues, and satirical cartoons.

While it was not the only alternative media to emerge from the mobilization of migrant communities in the United States, it was essential in challenging existing power structures.

It did so at first in a humble way, distributed biweekly to grocery stores in the Mexican-American neighborhoods of California's Central Valley and costing 10 cents.

By 1965, El Malcriado had some 18,000 subscribers and made the leap to Los Angeles communities thanks in large part to its bilingual publication and increased circulation in English. It still continued to primarily target farmworkers.

RELATED CONTENT

In fact, much of its initial popularity was due to the high-profile grape strike in Delano, California led by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). El Malcriado actively participated by mobilizing its readers and encouraging them to join the strike to make their voices heard.

As was commonplace in those years, the FBI accused eventually El Malcriado of being the pamphletary media of Chavez and the NFWA, whom they labeled as communists. The FBI even offered $1,000 to whoever had proof that both the newspaper and the union were red spies.

At the same time, within the newspaper itself, discrepancies were also spawning.

Chavez began to realize that El Malcriado was playing on its own in some matters when part of the staff refused to support Pat Brown's campaign for governor of California in 1966, while the union leader and the NFWA had given him their support.

U.S. intervention in the Vietnam War was also a point of major contention. Many farm workers supported President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Chavez wanted El Malcriado to remain neutral on the issue while the rest of the staff was highly critical of the Mexican-American draft, even publishing a letter from a Chicano soldier encouraging the community to oppose the war.

With so much controversy and disunity between its creator's idea and the staff, El Malcriado suffered a bankruptcy, major casualties, and was bought out by the UFW. But that did not save it from demise, when Cesar Chavez clearly saw that it was no longer fulfilling the role expected of it.

Nonetheless, for a decade it managed to unite the agricultural struggles with that of the Chicano Movement advocates and in good part was a loudspeaker and an inspiration to new generations of activists and their heirs today.

LEAVE A COMMENT: