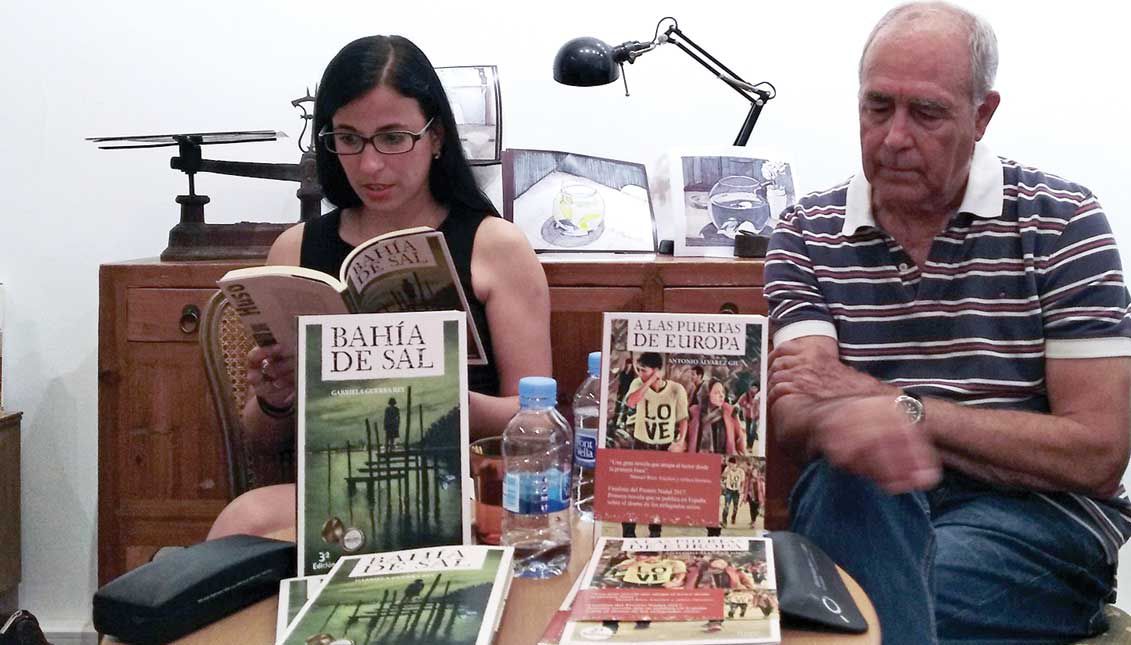

Gabriela Guerra Rey: a sea of Cuban nostalgia

Gabriela Guerra Rey, a Cuban writer who emigrated to Mexico, is the author of “Bahía de Sal,” a fiction novel in which she describes the dramas experienced in…

Gabriela Guerra Rey still remembers the sadness of having to say goodbye to all of her friends who decided to leave Cuba in search of better lives outside the island.

"The toughest times on the island grabbed me when I was a teenager. And then, it was my turn to leave," said this young Cuban writer, winner of the Juan Rulfo Award and currently living in Mexico City.

Born in Havana in 1981, Guerra Ray is one of the young promises of new Latin American literature. As her father was a writer and her mother an editor, she grew up surrounded by literature. She studied economics at the University of Havana and journalism at the José Martí International Journalism Institute, also part of the University of Havana. In the beginning, she worked as a reporter, but creative writing was already something in her blood, something she had at home every day.

"My parents were my first correctors, they returned all my texts marked in red," Gabriela recalled during the presentation of her novel in Barcelona at the beginning of June. Published by Huso Publishing, "Bahia de Sal" was awarded the Juan Rulfo Fine Arts Award for First Novel in 2016, an award that the Secretariat of Culture and Tourism of Mexico convened through the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature, the Government of the State of Tlaxcala and the Government of the State of Puebla.

"I wanted to transfer to the protagonist of my novel all those experiences that I lived as a young person, that feeling of experiencing an exodus in circles, to see people arriving and people leaving," Gabriela explained about the novel, which takes place in an imaginary town.

However, "my friends from school who have read the book could immediately see themselves portrayed in there. They recognized our hometown, our experiences," said Guerra Rey, who now lives in Mexico City, where she works as a journalist and is co-founder and director of the communication agency Aquitania Storytelling.

Although the town where "Bahia de Sal" unfolds could be anywhere in the Caribbean, "it is a town stalked by extreme weather and there is all these people who want to leave and they have to cross a sea infested with sharks,” the author said. “So one can imagine that it is somewhere in Cuba at the time that Cubans wanted to get on a raft in search of a promised land, or without even knowing what they would find."

Gabriela spent the worst years of the Revolution - the so-called "Special Period" - during “that time that one goes from being a girl to a teenager" and, unlike many of her friends, she did not leave the island.

"I understood the fall of socialism when my mother told me that we had four cans of condensed milk and then there was no more," said the author in a previous interview with Efe, shortly after receiving the award.

It was not until 2010, after finishing her journalism studies and having already worked for some months in Mexico as a correspondent for a Cuban media outlet, that she decided to leave the island too. Instead of heading to the United States, like thousands of Cubans did, she preferred to move to Mexico City and consolidate her career as a journalist and writer there.

"My mother's family is in the United States. I could have gone there, but I do not like the American way of life, at least that of the immigrant in the United States, who in order to survive has to do whatever it takes," Gabriela admitted during an interview with AL DÍA News in Barcelona.

In Mexico, on the other hand, "Cubans are highly esteemed in the professional sense. There is no Cuban who has not done well there, from setting up a restaurant to being a journalist or working in the university,” she said. Mexico is also a good place to be a journalist, "with so many stories to tell," although she sometimes admits that she was scared.

"When I was working for the Cuban media, which is very critical of the Mexican government, I was called a lot from the (Mexican) cabinet to complain about my articles. In fact, they were my best readers," she recalled, laughing.

RELATED CONTENT

Currently, Gabriela is a regular contributor in various Mexican media, manages her own communication agency, and also finds time to write essays and poetry. The first book she wrote in Mexico, "Nostalgias de La Habana," is a testimonial book, written in first person, "where I turned all my accumulated nostalgia. It was like a volcano that I felt inside of me," she said.

"Nostalgias de La Habana" will be published at the end of this year, after the success of “Bahía de Sal,” which, in fact, she wrote after. But, as Gabriela said, fiction is easier to sell.

Divided into 42 chapters, "Bahía de Sal" concentrates "all the dramas that human beings can experience," the author said. She is convinced that any reader in the world, from Mexico to Philadelphia to Barcelona, can connect with her story. The novel addresses “common” dramas, like the loss of the first love or growing up in poverty, but also particular ones, like living in a town under the threats of extreme weather, having to witness the continued migration to the United States, depopulation, or how prostitution expands as many Cuban women rely on sex tourism to earn money.

"In Mexico there is still the bias of believing that Cuban women are always willing [to have sex], it's something that I have to deal with on a daily basis," she said. However, Gabriela said that she feels comfortable in her role of being an immigrant in Mexico, although sometimes "it implies that feeling of being and not being."

"The moment you want to leave your country, you really desire it, you know that you have to break the ties and get out of there; but when you leave, you stay a bit like floating”, she said, trying to explain how the migrant feels wherever he or she goes.

"Bahía de Sal" explores the phenomenon of migration, but also talks about those who decide not to leave, the way people are rooted to places that are sometimes inhospitable, and all those people who arrive and do not leave.

"Many people probably were watching the news on the volcano in Guatemala and asking themselves: ‘Why would some people want to live under a volcano that can explode?’ But the same happens in my hometown, which every year is scourged by cyclones, or in the country where I live now, Mexico, which is threatened by earthquakes," she said.

"It's like that: when you are linked to a town, you stay," she concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: