Trench Art: When the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared on a tortilla

At the turn of the 21st century, a group of Chicanx "artivists" came up with the Great Tortilla Conspiracy. Now the collective is part of a "revolutionary"…

Religious fervor operates in curious ways at times.

Who hasn't read about the "miraculous" appearance of Christ's face on toast or a venerated slice of ham because someone thought they saw the Virgin's mantle on it?

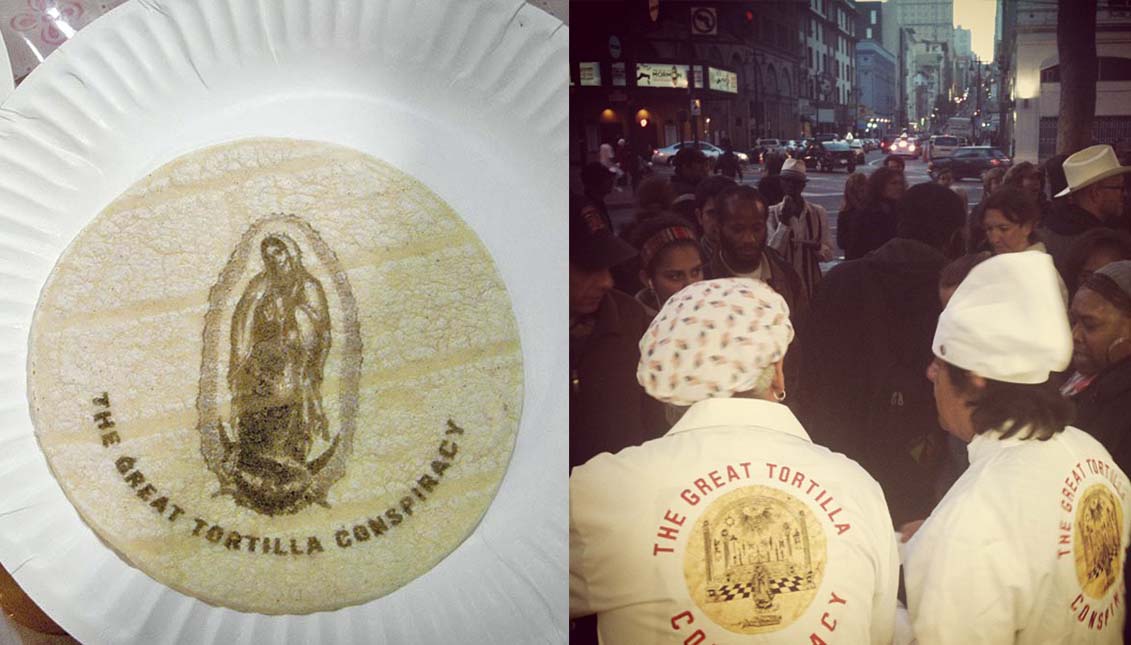

Through these eccentric visions of faith, and with a dose of humor and satire, artists Jos Sances, Art Hazelwood, René Yáñez — founder of the Galería de la Raza in San Francisco who died in 2018 — and his son Río Yáñez created The Great Tortilla Conspiracy, "the world's most dangerous tortilla art collective," in the early 2000s.

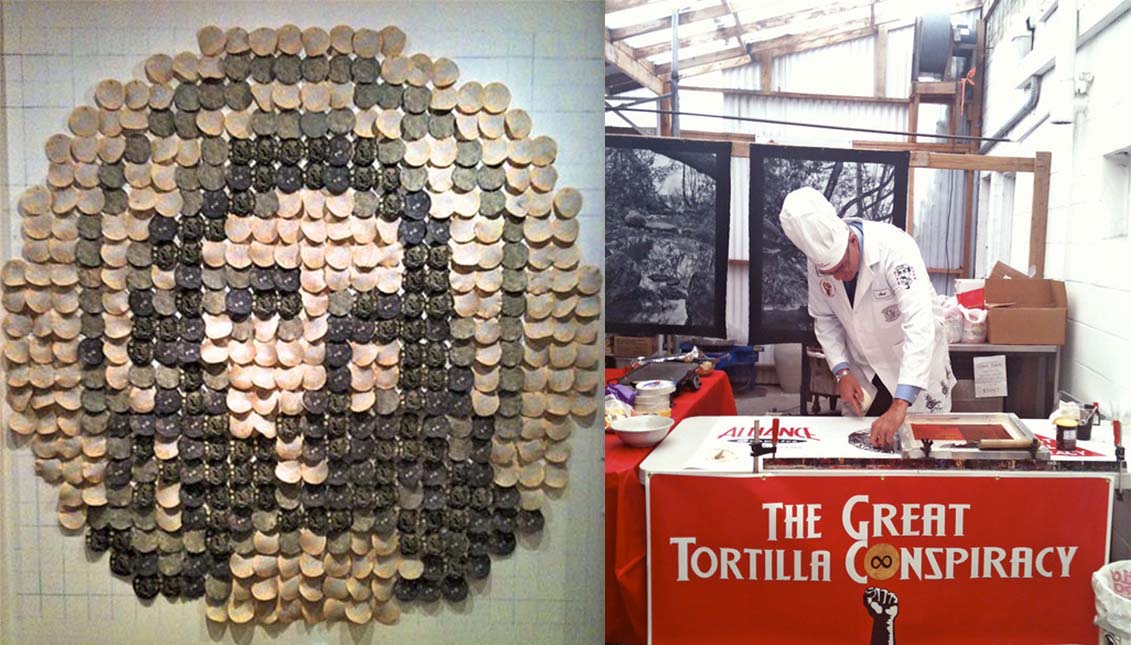

The initiative was to making "edible art of revolution," as Hazelwood cited in his 2009 membership appointment.

Using little more than corn tortillas and edible ink — chocolate syrup and dye — the San Francisco-based collective began creating silkscreen prints of iconic figures such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, or the artist Frida Kahlo, revered for mere seconds by the public, only to end up in their stomachs.

Their works were a performative process full of black humor, where they united the sacredness of Catholic rites with the symbols of Mexico, and presented themselves dressed in lab coats to "cook" these communions of enormous hosts consecrated by absurd art.

"An artist inspired by the cowboys of yesteryear folded a hanger into a sacred shape and branded the tortillas with the image of the saint."

The Great Tortilla Conspiracy also had a gospel, delirious dogmas, and even a particular cosmogony that explained its birth, following, as they themselves explained on their website, the model of Freemasonry:

"The founding document of the Conspiracy cites the miraculous apparition of various deities, including the Virgin of Guadalupe, on various surfaces — clouds, rocks, folded clothes — as well as on various foods... most famously, toast," they proclaimed.

"The roots of miraculous apparitions on tortillas go back to the early days of the Galería de la Raza in the Mission District of San Francisco. An artist inspired by the cowboys of yesteryear folded a hanger into a sacred shape and branded the tortillas with the image of the saint. Although the tortilla plays the central role in the aesthetic practice that is the Great Tortilla Conspiracy, the results were not always edible," they continued.

Eventually, however, they came up with "a secret recipe described as delicious by many quesadilla acolytes," and undertook a project that, beyond the joke, had a powerful meaning: to create community through free food and to make a spicy "satire" of Mexican-American cultural heritage.

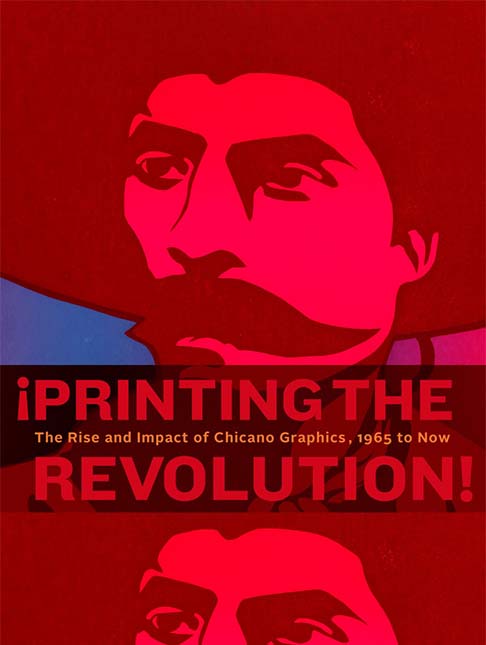

The works and history of The Great Tortilla Conspiracy are now part of the exhibition ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, hosted by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., which is reopening this year but whose works can be viewed in its online gallery.

¡Printing the Revolution! is an opportunity like few others to discover more than a hundred works from SAAM's pioneering collection of Latino art and to immerse oneself in the convulsive decade of the 1960s, when printmaking became the main medium for numerous Mexican-American artists parallel to the struggle for civil rights, and the feminist and LGBTQ movements.

It's a sum of aesthetics and politics through printmaking that has rarely been considered when exploring the Latinx revolution. Branded as "political propaganda," it was an engine of artistic inspiration through its colors and graphics that exalted identity and social justice.

From portraiture to satire, appropriation, politicized pop and conceptualism to its imprint today in digital art, the works of artists such as Rupert García, Ester Sánchez, Malaquías Montoya, and the Real Fuerza Aérea Chicana laid foundations in art, but their contributions were greatly minimized.

As the exhibition organizer and curator of Latinx art at SAAM, E. Carmen Ramos, explained the purpose:

"U.S. art history has yet to fully grasp Chicano artists' fluid negotiation between aesthetics and politics, and continues to place these artists in segregated tracks that rarely acknowledge their interconnectedness with the broader history of art," she said.

Today, the history of Chicanx art is back in print thanks to ¡Printing the Revolution!, and, as long as the pandemic allows it, you can enjoy the numerous talks, as well as the extensive catalog of the exhibition, published by Princeton University Press, which includes essays by scholars of Chicanx and Latinx art and graphics such as Terezita Romo and Tatiana Reinoza.

LEAVE A COMMENT: