Art bridges divides for immigrant children in Philadelphia

Mexican-American artist and art educator Nora Litz explains why art education is so powerful for children who are immigrants and from first-generation…

Artist and educator Nora Litz has been working with children who have migrated to the U.S. and children of parents who have immigrated for most of her career. As she describes her work in the art space at Puentes de Salud — the immigrant health and wellness organization in Philadelphia founded in 2003 — her voice is soft. But her words are firm and clear when she talks about the language of art.

“I know what art does, with those feelings and with those unnamely things that you go through life without speaking about it or being able to talk about it,” Litz said, who is careful to clarify that her art classes and works are not therapy, or art therapy, because she is not a therapist. But she believes and has witnessed the power of art to help immigrant youth find a voice and express their fears and experiences.

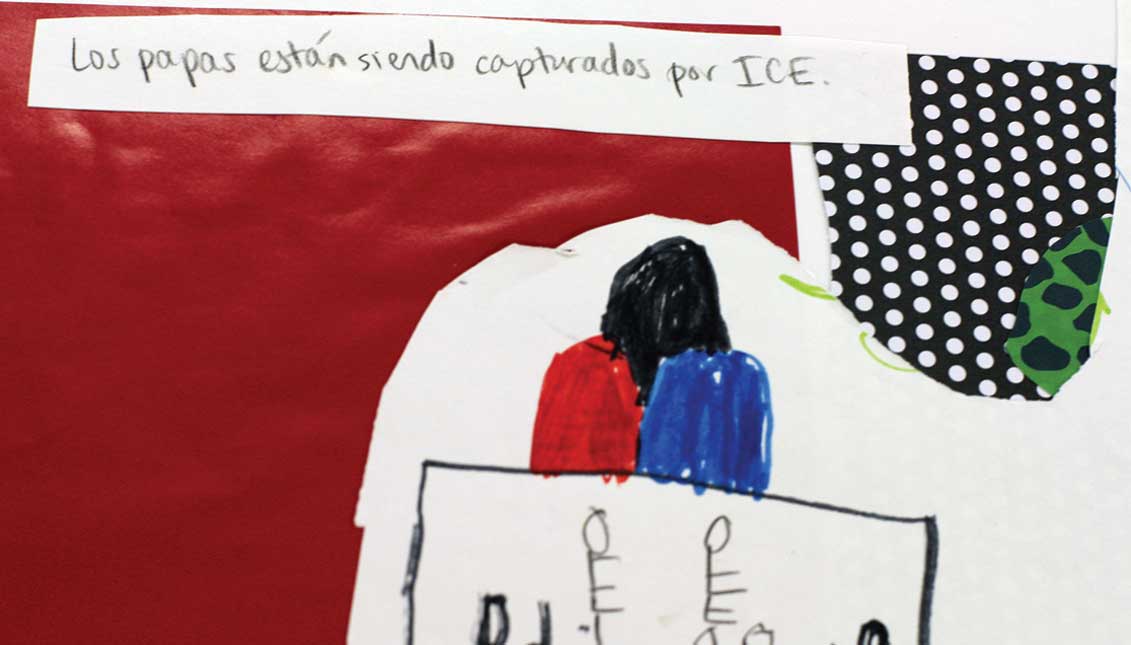

The stories children tell in Litz’s classes are heartbreaking all the more for the fact that they are not so abstract, or unrealistic. The same scenes of separation, goodbyes, walls, and parents being arrested by ICE that pass through the pages of the daily newspaper are captured in the scrawled, uncertain hand of a child, depicting both the lack of control yet complete comprehension when faced with the complexities of living as an immigrant or as part of an immigrant family in the U.S.

The artist and educator said that making art in the form of comics, dioramas, or other kinds of drawings and means of expression, can open up doorways for communication for children who are otherwise afraid to express their feelings, or simply don’t have the words — as shown in the project she did with artist Michelle Ortiz in 2011 called El Viaje, which included recorded stories and dioramas created by immigrant children, many of whom had begun their journeys in one of the countries that makes up the ‘Northern Triangle.’ The dioramas, displayed in part at Puentes de Salud, display those stories from the viewpoint of the children themselves.

After President Trump was elected, Litz created a class that allowed immigrant children to explore their response to his rhetoric and actions on the campaign trail and in office. The weekend class, held this past winter with Mighty Writers, another nonprofit organization in Philadelphia, provided space and guidance for children to illustrate their own immigration stories. Their work was later featured in publications such as Buzzfeed and Newsweek en Espanol; a recognition both fitting and disturbing because of how accurately the nightmares drawn by the children reflect the fearful reality for so many immigrants in the United States.

But those fears are better managed when shared, and art, according to Litz, is often the only form children have to express those “unnamely” things, the fears which grow, hidden even from their parents, who are struggling to confront many of the issues themselves and are hoping their children can grow and thrive, as unaffected as possible by the images and words they are bombarded with from blaring TVs and radios.

“What is very impressive is that when you start asking their stories they just come right out,” said Litz, explaining that for many of the kids she works with, they have been or are being raised by their grandparents, or have been separated from their mother and father because the parents were here in the U.S. and they were raised in their home country.

RELATED CONTENT

“The parents are not able to talk, and the kids know that, and even if they were born here, they have that stigma that they’re hiding something. They have that sense that they were born here so they have rights that their parents don’t have,” Litz said.

“So their understanding is amazing, but yet the emotional part is the part that’s not being addressed that art will do,” she continued. “Also for the parents to read what the kid was writing and to realize that oops, my kid has been listening, they’re so aware to all of this, so we need to talk more.”

“So their understanding is amazing, but yet the emotional part is the part that’s not being addressed that art will do,” she continued. “Also for the parents to read what the kid was writing and to realize that oops, my kid has been listening, they’re so aware to all of this, so we need to talk more.”

For Litz, who has lived her own immigration story after coming to the United States from Mexico as a 24-year-old to study art in New York, one of the most important aspect of the projects she has worked on is the collaborative element, informed by participants and directed by the students themselves. Currently, she is co-creating a project of life-size self-portraits constructed out of paper mache with DREAMers and other young people who didn’t qualify for the program but also arrived in the U.S. when they were young and are still undocumented.

With the DREAMers, 78% of whom are from Mexico, and others, the artist has witnessed time and again how immigration from her home country of Mexico has put many people betwixt and between.

“You come from a community and here, you don’t live in a community. This is not communal life. This is individuals. So I started thinking what to do about it and since I’m an artist so I started doing art,” said Litz. Art that is community-based, and incorporates storytelling and sharing out loud before the pencil even hits the page, as Litz strives to ensure the classroom space is safe and welcoming.

“Just being together with the other kids will give them this sense of calmness, of nothing is happening, or if something is happening I’m able to talk about it and it’s important whatever I think about this whole thing,” Litz concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: