An exclusive conversation with Guillermo Arriaga

The screenwriter of "Amores Perros" and "21 Grams" spoke to AL DÍA about his latest novel, Save the Fire, and his deep love for the border.

Guillermo Arriaga knows the border like the back of his hand. All of them, he says, outside of Sonora.

"Since I'm a kid, I go to the border five times a year and I have a deep love for it," he says.

He plans to go live there at some point and, as he describes it –"a territory all by itself," "one of the best places in the world" that those who don't know judge lightly– he gets me to want to take a plane and move there too, to meet the people who appear in his books, who are frontiersmen, a little like life.

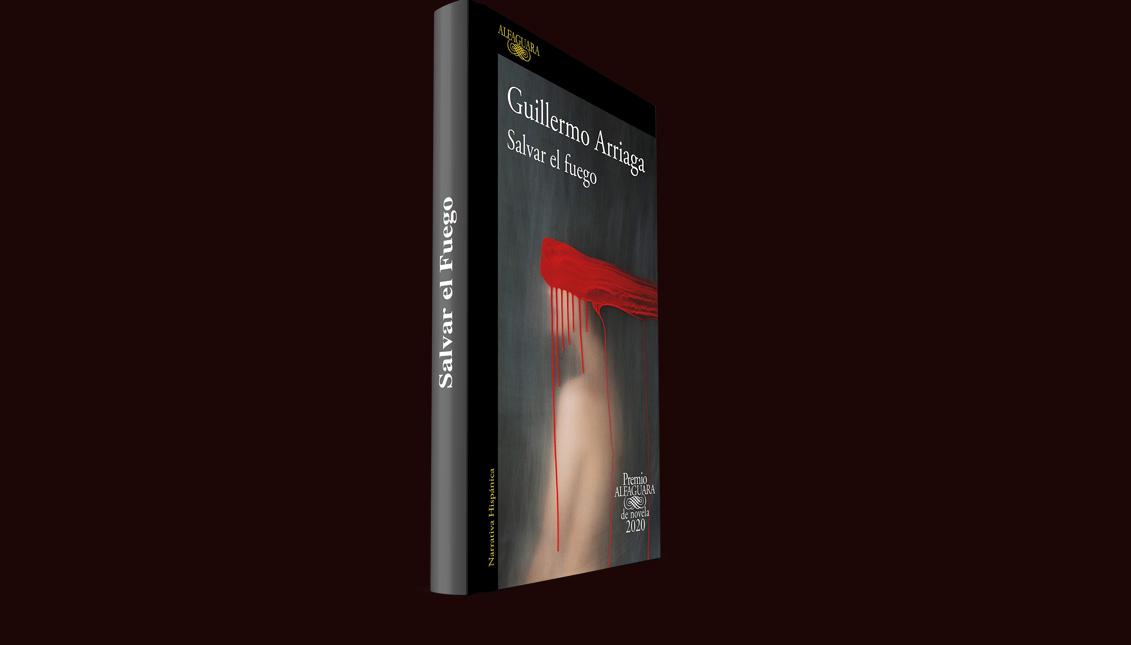

Or like all his novels, especially the last one, Salvar el Fuego (ed. Alfaguara), where there are walls as high as a prison’s, but that his characters jump nevertheless.

He opens his sweatshirt and proudly shows me the t-shirt from the Unidad Modelo colony, where he and the protagonist of his novel, José Cuauhtémoc, grew up.

Cuauhtémoc is a güero Indian imprisoned for accidentally dealing narcotics, a social outcast, and the son of an indigenous hero who falls in love with an upper-class dancer, Marina, so lacking a creative fire that only in prison and in Cuauhtémoc's arms does she find a way to light it.

"Mexico has a complex relationship with its roots. There is not a single monument to Hernán Cortés, and even if a child at school makes a mistake and says his hero is Cortés, he can be expelled. Our heroes are Cuauhtémoc — the last Aztec emperor — or Xocoyotzin. There is a greatness of the indigenous and at the same time if they insult you, they tell you that you are an Indian. A 'patarrajada', a 'fool like an Indian'," says Arriaga.

Salvar el Fuego is a novel written without method, with the crackling of the fire whispering in the reader's ear for more than 600 pages, but it addresses many burning issues: violence on the border, racism and roots, snobbery of art and love — which is never chosen — and the extreme and always touching death, two of the recurring themes of Arriaga's literature.

"I don't know why they say I'm talking about death when I'm talking about life," complains the Mexican, for whom love and literature have a lot to do with hunting, even though there are those who say you don't kill what you love.

"If bow and arrow hunting has taught me anything, it's that we are nature, and love is nature too. We hunters love animals deeply, which is something that animalists do not understand. The act of hunting really lasts ten seconds, but when you see a picture of a hunter with his prey what you are seeing is the end and not the process, like when you see a couple making love and you think it's porn because you took away the whole act of seduction and falling in love from before. Sometimes when I hunt I get angry with myself, other times I get sad; it's a very strange feeling, like love.”

Arriaga couldn't write a single line if he didn't hunt.

"If bow and arrow hunting has taught me anything, it's that we are nature, and love is nature too."

With the frank humility with which he speaks, always from ‘compadre to compadre,’ he tells me the stories behind the characters in his novels; anecdotes gathered in the rancheríos, boys who became hitmen because they had no other choice, people so humble they would give you the shirt off their back.

Many of them, he assures, are his friends.

"We writers are vehicles for telling stories. I'm not a migrant, but I'm a friend of migrants and even a godfather to their children. Am I appropriating their experience or trying to express what they can't?," he asks when queried about controversies like the one surrounding American Dirt.

For Arriaga, the Mexican reality is not dichotomous, but there is a whole range of individuals who are neither good nor bad, whom life has placed in a particular circumstance, and who knows if they had no other option.

"There's a lot of rot, of course, but I've met commanders whose corruption is impossible. I have also known many people who out of anger and frustration either migrate or get into the drug trade. But my fellow migrants are desperate, not angry,” he said.

“Then I've met others who say, 'You know what? I watch the dog food commercials and they eat better than I do. And you know what? I'm less than a dog and I don't mind killing little bourgeoisie," he says, using his ability to take us inside people and characters to see how the world expresses itself through them, which is where cinema falls short.

Thus we see ourselves possessed by the ghost of Ceferino, the father of José Cuauhtémoc, a man with his bright spots and shadows, a national hero and a defender of the indigenous cause who, within the four walls of his home, is a monster.

“Ah, yes," says the writer, "we have all known such people, capable of the best and the worst, who marry a Spanish woman with the idea of reversing colonization as Ceferino did, or lock their children in cages to make them hard. That, by the way, really happened. It happened to a compadre," he adds.

RELATED CONTENT

Of course, not everyone is a drug dealer and a person hardened by life.

In Salvar el Fuego he also reflects on art, that which is either born from the head, or from emotion; or from the cock, as happens to José.

“I think I write with my dick too," says Arriaga. “From the middle of the body down, but never with the head.”

And it doesn't matter what you believe in, or even why, because what defines art, he says, is permanence.

"There are writers who are spoiled children, like Borges, and writers who come from the mud, and all of them have made masterpieces. There is no such thing as true art, and it comes from where you least expect it," he says.

"We writers are vehicles for telling stories."

When Arriaga can't find a word, he makes it up. Something, he says, that will be understood above all by border readers, who are very fond of mixing Spanish and English to talk about "washanderías" (instead of "laundry") or "liquearse la pipa" (to lick the pipe).

In this way, Salvar el Fuego is a rare and fun combination of border slang with chilangas and even boricua expressions like "safacón" ('safe a can') and other neighbors of Old Spanish or born of their own imagination.

"It's something I've been doing since my first novels, and I blame a Spaniard, Pío Baroja, who said he wanted to squeeze the language out of the words he couldn't find, but he used the ones he had," she says. "For example, 'atipulado', which can mean 'groomed' or 'well-dressed'. Some people told me it was going to be untranslatable, but Joyce did the same thing and he didn't care. If they don't understand me, then what am I going to do?," the writer jokes.

He goes on to describe "the borders" — not one but many — between the United States and Mexico. Guillermo Arriaga finds it fascinating and disturbing that people talk about "Latinos" to mean cultures as different as that of a Cuban in Miami or a Chicano in Texas.

"They are even enemies," he says.

Or the difference between a Puerto Rican from New York and a Salvadoran from Los Angeles.

"The gringos do the same thing the Spanish did by calling all the indigenous cultures Indians, putting everyone in the same boat. That's why when I've dealt with Hollywood executives, they think they can talk about the Latino audience and want to put a Cuban actress with Mexican handling the different segments for Hispanics, but they have no idea what they're talking about,” he says.

He confessed his novel was going to be called The Lion Behind the Glass, but he changed it while the fire became more and more lit on each of its pages.

From the beginning, I see Arriaga on the other side of the screen, with a wall of small wooden logs behind him, as if he were in a hut, and I think that his writing, just like the people on the border, who invent a language just like he did, cannot be put in a cage. Even if they try, they both have the virtue of the hunter: to know how to "become a bush.”

LEAVE A COMMENT: