The historic Chicano Moratorium: Aztlan's warriors keep fighting for their rights 50 years later

Half a century has passed since the largest anti-war march by an ethnic group in the U.S. that was marked by police violence. What has changed after Black (&…

"It was wonderful," the eyes of 74-year-old activist and historian Rosalío Muñoz, one of the organizers of the Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1970, shine in front of the camera recalling the moment when LA Times journalist Ruben Salazar came up to him in the middle of the march, gave him a big hug and congratulated him for bringing together nearly 30,000 people marching through the streets of East Los Angeles with banners showing slogans like "Aztlan," and "Stop the Chicano Genocide" could be read.

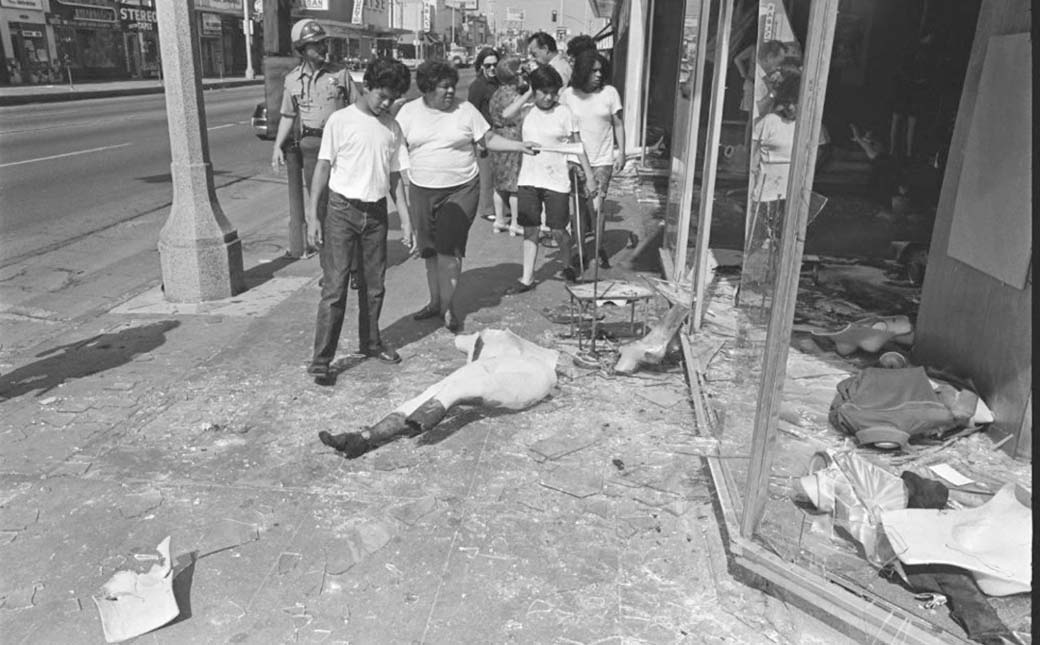

No one sensed that just hours after the protesters began their pilgrimage in L.A.'s Belvedere Park, their anti-war proclamations were going to end in a pitched battle with hundreds of detainees, some 60 wounded and three dead, including Salazar, who was at The Silver Dollar, a local cafe, when the riots broke out and was hit by a tear-gas canister fired by the sheriff's deputy — the causes of his death remain obscure.

Salazar is now a martyr to the revolution, whose figure has taken on new historical significance in the context of the protests against police violence and for the Black and Brown lives that are shaking the country after the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and many others. It's proof that journalism — which many believe to be dead — has the power to make visible the greatest injustices and give voice to communities.

However, these deaths also show that history is not a timeline that advances, but that we are doomed to repeat the same mistakes, or to suffer from them unless we manage to keep the memory alive.

For Chon Noriega, professor and director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, police brutality against ethnic minorities and journalists is common to this country's past and present, even though we are, as he says, reaching "a turning point in our society":

"The Chicano Moratorium — like the East LA Walkouts for better education in 1968 — were met with excessive police violence. But with the Chicano Moratorium, the police also shot and killed the most prominent Chicano journalist at that time, effectively silencing a crucial voice for social justice that reached the mainstream. Neither the courts, nor The Los Angeles Times (where Salazar had worked), challenged the use of deadly violence against a journalist. If we look at the situation today with Black Lives Matter, it is clear that little has changed for Native Americans, African Americans, and Latinos. These groups continue to be killed by police at much higher rates than for whites. And as the current protests have continued in cities across the country, the police have also started attacking journalists," said Noriega.

In 1970 there were many Chicanos who, like journalist Ruben Salazar, did not get their money's worth. Nixon had promised to end the Vietnam War and stop sending men to the front lines. But he did the opposite — recruiting more and more soldiers, who returned home coffins. The proportion of young Chicanxs that died was overwhelming, with no real count of government casualties — 10% of the citizens of the southwestern states were Mexican Americans, and 20% of them died in Vietnam.

Most of these young people had been recruited as a result of precariousness. The huge disparity in wages and education left very few options for Latinos, as Professor Thomas Summers Sandoval of Pomona College recalled: "Many Latinos did not qualify for deferrals because they dropped out of school or were not enrolled in college."

Those who were not drawn into the war, fought it at home.

"If we look at the current situation with Black Lives Matter, it is clear that little has changed for Native Americans, African Americans and Latinos," Chon Noriega.

They did so in many cities, but the Aug. 29 march in East Los Angeles was to go down in history as a bittersweet event, which for many of its participants was both a reinforcement of their identity and the beginning of an entire generation's disenchantment.

"It was part of an entire network of oppression (...). Latinos were the least successful in the eyes of the government, but when it came to war and the need for cannon fodder they were top-notch," said Rosalio, who had also been ironically called up on Mexican Independence Day, and was then a promising young student at UCLA. In fact, a student leader.

Muñoz organized the Chicano Moratorium with activist Ramses Noriega. Many more university activists and entire families joined, some of whose relatives had been drafted. The reaction to a riot, hours after the peace march began, turned the streets into a war zone.

RELATED CONTENT

Today the echoes of those protests, Salazar's death and the inflammatory images in the media are still more alive than ever in the hearts of the heirs of the Chicano movement. They are the Nueva Raza.

"We still have a lot of work to do to stop the war at home, in our neighborhoods, and wars around the world," says Guadalupe Cardona.

Lupe is one of the organizers of the march that each year commemorates the Chicano Moratorium and will take to the streets again on Saturday led by legendary activist Gloria Arellanes and the mothers and families of murdered young Chicanos.

But this year, nationwide protests against institutionalized racism and a looming election have added new nuances to tomorrow's march — "We must get Trump and the racists out of office but we must also be critical of anyone who replaces them," Lupe says. The present turmoil has enhanced the historical significance of the great Chicano demonstration.

"We must look to our ancestors and the seven generations before us so that we can be strong for the next seven generations," Guadalupe Cardona.

"We stand in solidarity with our African/Black brothers and sisters in their fight to stop police terror and for Black liberation. We also acknowledge that since the murder of George Floyd 68 Brown men have also been killed by cops," added Cardona, who is part of a 20-member committee working to keep alive the spirit of the movement and the legacy of Ruben Salazar.

"This is an event that brings us pride but also It helps sustain the Chicano identity. We must look to our ancestors and the seven generations before us so that we can be strong for the next seven generations," concluded the activist, for whom the development of Ethnic Studies is a key issue. Many young Chicanos in California today are unaware of part of their identity and history. Advancing against forgetfulness is part of the struggle.

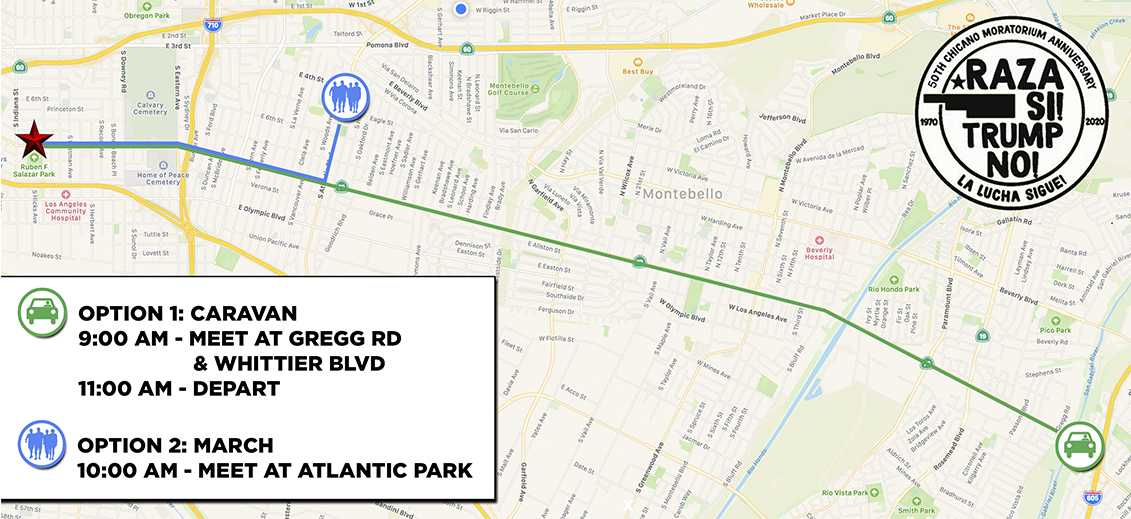

The celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium will begin at 10 a.m. from two points: You can join the caravan of cars at 9 a.m. on Gregg Rd. and Whittier Blvd. in Pico Rivera, or walk in the march from Atlantic Park at 10 a.m.

Here you can follow the map:

LEAVE A COMMENT: