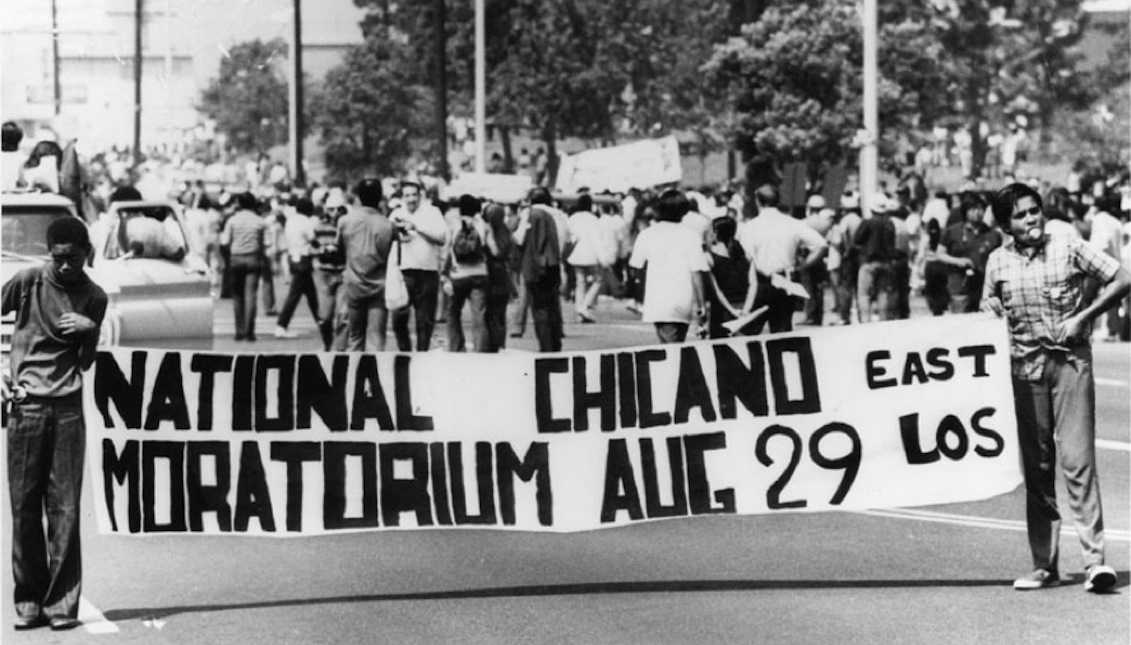

The memory of a struggle for Chicano identity

This August 29 is the 47th anniversary of the day when thousands of people marched in the east of the city of Los Angeles to protest the great casualties of…

The Chicano Moratorium, better known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, was a movement against the Vietnam War and was based on the coalition of several groups of Mexican Americans, led by student activists and members of the Chicano organization Brown Berets – a group founded in 1967 by David Sánchez, former president of the Juvenile Council of the Los Angeles City Council, during the Civil Rights Movement era, with more than 5,000 members claiming the Chicano presence in the institutions that affected them, in what they called The Spiritual Plan of Aztlán.

This fusion of movements reached its peak in the demonstration on August 29, 1970 in the eastern side of Los Angeles, which brought together more than 30,000 people.

Demonstrators contested the fact that the Chicano community represented only 5% of the total population in the United States, and were still one of the most deadly demographics in the war (about 22%). "The frontline is not in Vietnam, but in social justice, within the country," they said.

The groups organized two demonstrations, the first of which was held on December 20, 1969 and had about 1,000 participants, and the support of the Crusade for Justice group based in Denver, Colorado, who led the organization of other demonstrations throughout 1970, and that they demarcated in a multitudinous march on August 29 in Los Angeles, with simultaneous rallies in cities like Houston, Albuquerque, Chicago, Denver, Fresno, San Francisco, San Diego, Oakland, Oxnard, San Fernando, San Pedro and Douglas, which had about 1,000 people each.

Demonstrators contested the fact that the Chicano community represented only 5% of the total population in the United States, and were still one of the most deadly demographics in the war (about 22%).

The main march in Los Angeles was concentrated in the old Laguna Park (now known as the Rubén F. Salazar Park), and had about 30,000 participants from all over the country, which mobilized from Whittier Boulevard. Police intervened by force to disperse protesters, arguing that the rally was an "illegal assembly" and that many of those who were there had stolen a liquor store nearby. Between smoke and gas bombs and excessive use of the police force, more than 150 people were arrested, many injured and four others died, including the award-winning journalist Rubén Salazar, director of a local Hispanic television station and columnist at Los Angeles Times.

RELATED CONTENT

Protesters’ resistance and violence on both sides triggered the clash, but the death of four demonstrators and the lack of condemnation of police forces made the event a symbol of the struggle for equal rights.

The attempt by the media and the government to cover and forget the subject for years has only boiled a resentment that today is again in force: when justice is concerned, minorities are always last in line.

Almost 50 years later, this event remains unknown to most of the citizens in an attempt to hide the intolerance and over-power of the police forces against a community that gave its life for the country in the most unjust war.

As Dr. Juan Gómez-Quiñones explains in his column for the National Institute for Latino Policy, many of the witnesses of that fateful day are still alive and awaiting the recognition of the authorities for the mistakes made, and the perennial silence before the facts only keeps the wound open and the urgency to pursue a civil rights equality still unattainable.

LEAVE A COMMENT: