Venezuelan author talks literature, vampires, and turning pain into poetry

"For me, literature has been one of the most important things in life. I don’t know how to do anything else but to write."

Fedosy Santaella is one of the most outstanding Venezuelan writers of the moment. A writer of novels, short stories and poetry, some of his texts have been translated into English, Chinese, Slovenian and Japanese. He was finalist of the Cosecha Eñe Prize (2010), in Spain, winner of the Short Story Contest of the Caracas newspaper El Nacional (2013), finalist of the Herralde Novel Prize, winner of the Short Story Prize Ciudad de Barbastro in Spain (2016), and honorable mention in the 1st Eugenio Montejo Poetry Biennial (2017), in Caracas.

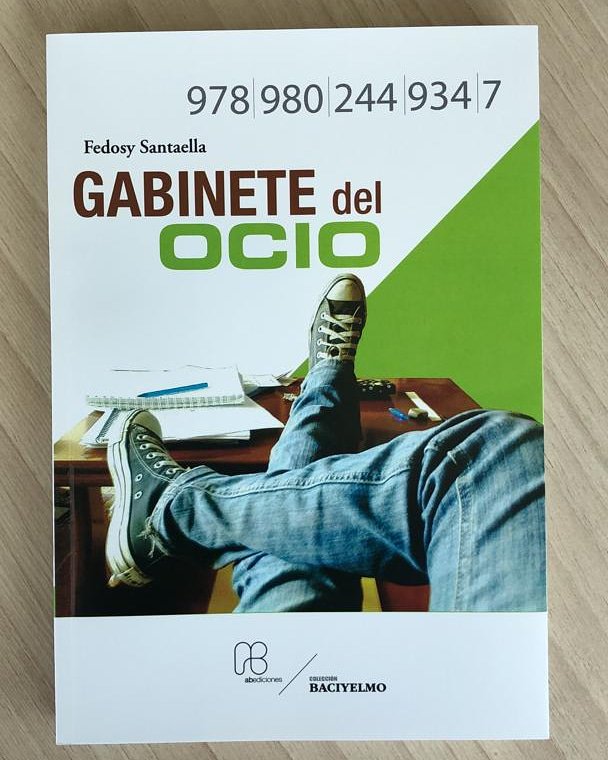

His last two novels, “Los nombres” and “El dedo de David Lynch,” were published by the Spanish publishing house Pre-Textos; his collection of poems, “Tatuajes criminales rusos,” published by Oscar Todtmann editores, and “El gabinete del ocio,” his most recent book, has just been published by the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, in Caracas.

“El gabinete del ocio (The Leisure Cabinet)” is an unusual book, with carefully thought-out essays and a mix of subjects ranging from vampires to Sherlock Holmes, childhood memories, tattoos of criminals, Boris Vian, medieval monks and much more. I talked to him about the origin and development of this book, about his creative process being an expatriate in Mexico and the people who continue to do culture in Venezuela, despite the economic storm the country is going through.

I've always believed that the epitaph on my grave should say, "Well, I tried.” I'm a person who's always trying. Trying to be a better person, a better writer, a better father, a better human being.

For me, literature has been one of the most important things in life, I don’t know how to do anything else but to write. If I had been a doctor my patients would have died, if I had been an engineer my bridges would have fallen, so I had no choice but to write and love literature. I really like knowledge.

Many years ago, in a city where I lived, Valencia, the capital of the state of Carabobo, I made friends with a broadcaster, because I was offered to do a radio program. And the radio program was on a jazz station, it was in the night zone: it started at 8 p.m. and lasted until 11 p.m. Then it was a tremendous opportunity for us: the manager liked us and we did the program. We could play the music we wanted at that time, but we also decided to make a program called “El arte del ocio” (The Art of Leisure), and look that the book is called “El gabinete del ocio” (The Cabinet of Leisure). In this program, I and my friend José Abel, who was the other presenter, what we did was that during the day we investigated things, each on his own, and then we met on the radio and talked. It was not a pre-produced program; we could talk as if we were in the living room of the house. Then I kept that idea of the leisure cabinet, and I transformed it into this book, which is that possibility of talking freely about an amount of things that interest me and putting them in this kind of old museum or pre-museum where each room had different themes or curiosities. In fact, some of those essays, stories and profiles have already appeared on websites, in digital magazines, and what I did was bringing them together and rethinking them under this cabinet idea.

Yes. For example, vampires: from my perspective, the study of vampires has always been from a semiotic, historical and literary perspective. But you usually say "vampires" and people get scared and run away. In fact, I did several events, as a research professor at the Catholic University Andrés Bello (Caracas), in relation to vampire literature and, of course, in the center where I was with the other researchers, they laughed at me. “There's Fedosy, with one of his vampire crazy ideas.” But I just like to take another look at things and dive deeper into them. When it comes to vampires, I'm interested in what they really mean from a historical point of view: the vampire is the other. Vampires were born on this Serbian-Croatian border, which was the Turkish Ottoman Empire, and when you wonder why: it is fear of the other. The vampire is the metaphor or the image of the stranger. In this case, the Turks.

Vlad the Impaler, who was a gentleman Dracul, is the image of that European who rejects what is different from him: he eats differently, he speaks differently. This idea came to me reading the origins of literature from folklore, from literature already printed, authorial, like Bram Stoker. I was curious, is this literature really the image of the foreigner? There, obviously, is an idea of xenophobia. That's where I got into the research and I came across the idea of the other, the double, the evil twin. I like to go into those fields and look for that serious part of what people don't consider to be so serious. For example, Sherlock Holmes was long considered entertainment, but how much literary quality is there? And how much can be said from a literary point of view about Arthur Conan Doyle's literature? That's how I get into the roots and into popular literature to get done something more serious and deeper.

Yes, I've been very interested in tattoos from a symbolic, spiritual perspective, I have tattoos myself. I'm not sure how I got into Russian criminal tattoos, but I've always been interested in getting into those Russian, Ukrainian, Polish roads.

In some ways, what happens in Venezuela has to do with that Soviet socialism, which was there for so long. There is an interesting parallel between what happens in Venezuela from the point of view of this supposed (or not) socialism and what happened in the Soviet Union. There I look at Russian criminals, not for victimizing them or for taking their side, but in many cases, they are victims of a system. They were taken there by an overwhelming, impoverishing state.

The tattoos were used to tell the souls of these men who are criminals but who are also those who suffered under Soviet socialism. They are also a metaphor for what is happening in Venezuela.

In “Gabinete del Ocio,” I was interested in tattoos from a semiotic and historical point of view. To think of the tattoo as a writing without words that says what cannot be said. And its relationship with evil and freedom was what interested me in the essay. I look at the historical moment, which is also very interesting because women take a leading role in the American history of tattooing. And Foucault has also noticed the significance of the tattoo, which is a writing that takes you somewhere else, that places your body somewhere else, and somehow makes you better than you are.

Foucault's observation in relation to Russian prisoners is wonderful because, through the tattoo, the criminal is saying who is out of prison. It's a writing that's saying who you are, even when it seems like you can't say it. And as a symbol of evil, because evil is a consequence of freedom, and the freedom of tattooing is in transgressing the body.

I wrote it in Venezuela. In those already horrendous years between Chávez's death and the apparition of Maduro. It was guarded for a time. I love poetry, but I find it very difficult to write, so the book was passed from hand to hand among poet friends: Jacqueline Goldberg, Eleonora Requena, they are somehow the godmothers of my book. The book changed a lot thanks to their advice. Then I gave it to a Venezuelan publisher, and the whole editing process was already with me in Mexico.

The Cabinet has some texts that were already published on other websites, such as El Estímulo. It's a compilation of texts that I wrote over four or five years. Of course, after publishing them on the Internet I modified them, I made them a little more academic and I perfected them, I corrected them. Many times, they were written with a rush of delivery due to the weekly pressure.

I made them a little more academic without losing sight of the fact that they were very free texts. I was still in Venezuela when I delivered the book almost two years ago. I delivered it and it was waiting for two years; publishing now in Venezuela is a privilege.

I was in Mexico when they wrote me to tell me the book already had a cover.

I love Mexico. It has an impressive culture in everything: music, food, literature...These people are ahead of many other countries, it's wonderful.

I've been writing here, licking my wounds. Now I'm going to publish there in Colombia with the publishing house Taller Blanco Ediciones, formed by a Colombian poet and two Venezuelans. The editions are small and also very nice because they are ecological books, hand-stitched, the paper is recycled... and they have published diverse authors: from Colombia, Spain, Venezuela.

The book I will publish with them is called the “Retablo de plegarias” (Altarpiece of prayers). It is divided into four parts and is about what is happening in the country. They are texts that are between the poetic and the narrative. I'm trying to write texts that aren't defined by a genre. The first part is about being in the country, the chaos. The second part is more nostalgic, melancholic, where I talk about the Caracas of the 90s; they are between chronicles and stories. The third part is made of long poems, which talk about the pain of leaving a homeland, but said in a very metaphorical way, talking about Mexico, Iceland, the United States... and, somehow, these poems that talk about other places talk about migration. The fourth part is already the poetic voice fixed in that other place, which is Mexico. It is what this poetic voice brought from its country to that other country. For example, the keys to my house. I have my house there in Caracas, but it's closed, it's empty, we can't sell it or rent it. We can't sell it because they're going to buy it for nothing, and we can't rent it because we run the risk that they won't give it back to us.

So, I'm talking about the keys, which I have locked here in a drawer. I'm talking about my grandparents, who are Ukrainians, who left because of the war. When they died, I was left with some crosses and a Ukrainian shield, which a friend of my grandfather made for my grandfather. That was in my house in Caracas and now they are here in Mexico.

RELATED CONTENT

That sword and that cross don't stop being pariahs. I'm talking about my books, the books I brought with me. It's painful, but I try to transform that pain into literature and poetry.

Right now, I'm writing a novel about a single mother in Venezuela. Her children are gone, her husband is dead, she is 60 years old. And it's the story of this single woman living the history of the revolution. She makes a trip to Mexico, she is with her children there, but she returns. It's a bit like the story of all these older people who are in Venezuela, who have their house or their apartment already bought. Their children leave, and they are left alone. They spend terrible nights because the light goes out. It is the painful story of this woman who, moreover, does not want to leave her country because it is her home, and because she is not going to be defeated by the revolution. I tell the story as if this woman were a ghost.

Her ghosts are her dead husband, the past she lived through. Nothing of that which she and her husband fought already exists, she lost it and it’s lost to the revolution. She tries to have an affair but cannot.

Sure. And the degradation of the country is also present. Many of the older people have already worked, saved and simply want to have a quiet life in spite of old age and illness. But these people of everything they had now obviously have nothing, and they don't have it because of the revolution, that's even more painful.

They are already grandparents, and in another country where the situation is more stable, they will have their grandchildren and their children. But these people will not. That loss is not because of age, but because the revolution has taken everything out, there are a lot of people in the country looking outside for a way to survive because it is no longer possible there.

Of course, my mom is there too, and that's why it's painful to write it.

It's a necessity. I could write a story about a minister of the chavismo, or some sexual pervert, and denounce it in a more pamphletary, and more explicit way — I could create a political novel. In this case I am also writing a political novel, but it is also extremely intimate. And I think that's the difference. Between writing a political novel that tells the great political events that tell you about dates, hair and details, as are usually the political historical novels. What this novel does is going into is the intimacy of the character, and demonstrating everything she is suffering in the revolution. It is, of course, a political manifesto, but the perspective is more intimate.

It touches me personally because the character I'm building is also my mother. Her two children are abroad and that she is having a really bad time there in Venezuela.

I bring her to me and she stays a for couple of months, but she wants to stay there, that's because that's her home. Even if the country is doing bad. She has already made her life, and even though that life collapsed, she wants to stay in her house, that house that is part of her spirit, of her soul. A house that is also another ghost.

Yes, and to that we must add that there is a pain being imposed on you: from a faction of the state that destroyed a country. But that pain is one that is not going to disappear no matter how much you write it down. Although, if you write it down, that pain is yours, and it becomes yours when you turn it into beauty. You can no longer be hurt by their pain, but now it is yours and gives you strength.

That's where the key to poetry and literature lies, in relation to politics and oppressive states. And it also has to do with Russian poets, who turned all that pain of the Soviet Union into a beautiful poetry that still speaks to us.

I reread “Aura” (by Carlos Fuentes). I reread Juan Rulfo completely: “Pedro Páramo,” “El llano en llamas.” And I'm reading a lot of contemporary Mexican literature like Guadalupe Netel, Antonio Ortuño, Alberto Chimal. And other contemporary Latin American authors like Samanta Schweblin. In poetry I've been reading Mark Strand, Nicanor Parra and Manuel Vilas.

LEAVE A COMMENT: