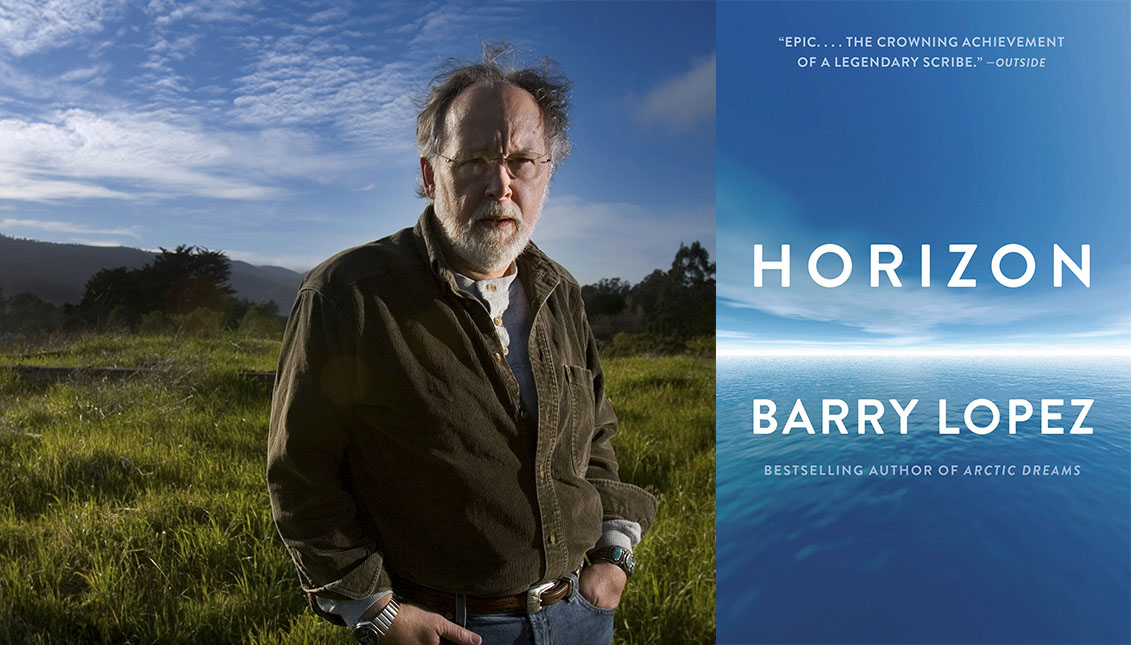

No one "talks" to nature like Barry Lopez did (Op-Ed)

The best nature writer in the United States died last December. But he left us a new way of seeing the world around us and of relating to it.

I have always thought that the landscape defines us as much as we define it. As if there were not a great difference between who we are and what surrounds us — a fusion of environment and person.

Barry Lopez considered nature his teacher, to the extent that he achieved what few have achieved: to put it in exact words. To describe the frozen immensity of the Arctic when adjectives fall short and the horizon becomes confused with ice. When this wild Mother Earth enters our hearts and, as I said, changes our perception forever.

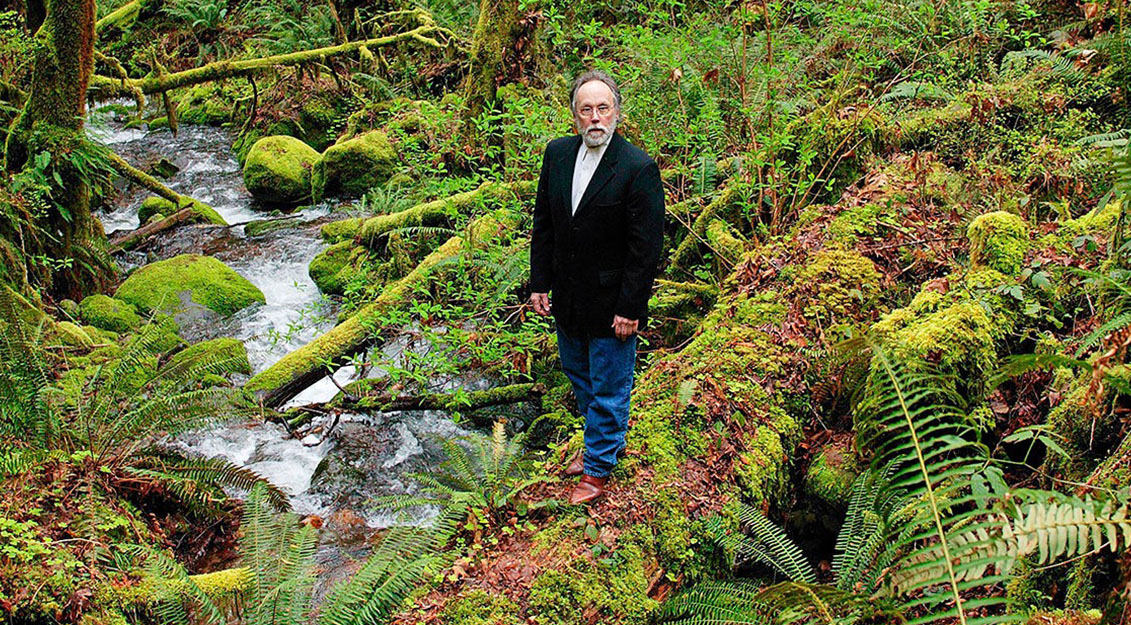

A tireless traveler, furious defender of this Great Master and author of some 20 books such as the marvelous classic, Arctic Dreams (American Book Award, 1986), where he recounted from the lives of the Inuit to the secrets of the polar bears or the history of ice, Lopez died of prostate cancer last December in his native Oregon.

It happened at the cabin he lived in the Cascade Mountains. Where, as he explained to me on the only occasion I was fortunate enough to chat with him, wild salmon breed in front of his house and it is common to see wild animals in the woods.

"This is the only place in the world that has affected me more deeply, because I have lived here, in the same house, for 48 years. It is the place with which I have had the longest conversation. Every year, the deepest conversation," he said.

And it's funny that he chose Oregon and not one of the more than 70 countries he visited and wrote about during his lifetime. As a nature poet, he explored the most inhospitable, beautiful, and extreme places on the planet.

Lopez was someone with a metaphysical and sacred vision of what surrounded him. He learned from traditional societies the value of community and the importance of scientists taking it into account because they had achieved a true "relationship" with nature that is self-regulating and sustainable.

"This means including the non-human world in one's moral universe," he told me. "You just need to see the world you live in differently."

Robert Macfarlane, another of the great nature writers of our time, defined Lopez as someone as austere as the landscapes he described in his books.

However, when it came to defending nature and criticizing the human and harmful activities on it, Lopez was like the magma of a volcano.

RELATED CONTENT

"The clumsiness of several Western governments in their approach to global climate change, ocean acidification or biodiversity has more to do with their desire to perpetuate capitalism," he explained to me in an interview for The Objective.

Unlike those who think, from a rather anthropological viewpoint, that humanity can destroy the planet, the writer was emphatic in his counter.

"Impossible," he said, "and Nature has no interest in rebelling against us either."

Lopez predicted that homosapiens — which are believed to be the center of the universe — were nothing more than a primate that was trying to disappear, and that if we did not change our way of relating to the environment, sooner or later, there would be a sixth extinction.

"As has happened with the five previous extinctions in the history of the Earth, life will flourish again, although I don't think Homo sapiens is part of it," he concluded.

We are in the world, but the world is bigger than us. And perhaps the key to it all, as the writer recalled, was what an Inuit revealed to the polar explorer Rasmussen — the first man to cross the Northwest Passage in a dogsled.

When Rasmussen asked him what happiness was for him, the Inuit answered as simply, as austere as life is (or should be):

"Finding a fresh bear print and getting ahead of all the other sleds."

With some nuances, perhaps Barry Lopez, who was all the places and all the words to name them, would have answered the same.

LEAVE A COMMENT: