Sergio Troncoso: “The border is going beyond the border”

The Mexican-American writer arrived with his family in El Paso as a child. His books tell stories of life on the border

The son of immigrant parents from Mexico, Sergio Troncoso grew up in Ysleta, a community in El Paso, Texas, as a fronterizo, or border child. But if anything truly influenced his childhood, it was growing up surrounded by strong women. “The most important woman who influenced me was my abuelita, my mother’s mother, Doña Dolores Rivero. She was a tough viejita who didn’t care about social niceties”, Troncoso recalled in a recent conversation with AL DÍA News.

He remembered he loved “listening to her violent and often heartbreaking stories of how people suffered in her rancho near Chihuahua. The family lore was that she had shot and killed two men who attempted to rape her during the [Mexican] Revolution. She could be vulnerable, kind, and violent all within a span of a few seconds, and I thought she was the most interesting character in my family. I often spent weekends with her, listening to her stories”.

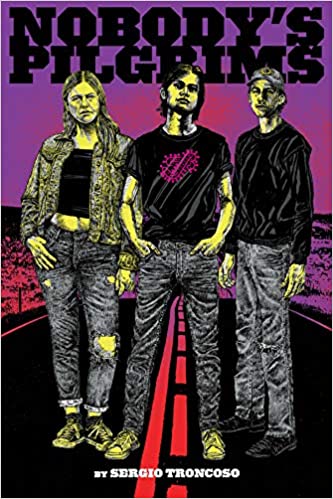

Author of eight books about immigration, Spanish culture, and the fact of being raised in a binational region as U.S.-Mexico border, Troncoso just published 'Nobody’s Pilgrims' ( Lee & Low Books, 2022), an adventure story about three teenagers, Turi, Molly, and Arnulfo, on the run from evil and unwittingly carrying an even greater menace in their stolen truck. “The border goes beyond the border in a story about who belongs in the United States and how finding your place in this world is about finding the right person to be with you. It’s a novel about the grit, intelligence, and luck of Turi, Arnulfo, and Molly as they face many obstacles, including an imagined United States collapsing because of a pandemic”, the author explained.

"'Nobody’s Pilgrims' was written before 20 cases of COVID-19 existed in the U.S., and in a way, the novel predicted the pandemic that was to follow. “The pandemic in my novel is transmitted by touch, and I just thought about what would tear apart this country and set us against each other. My answer was a pandemic. The three teenagers, all outsiders, forge a community of three, even as many around them turn against each other. And that’s what the novel is about: how we fight to stay together, how we struggle and succeed in becoming a ‘we,’” he said.

A NOVEL FOR EVERYONE

Although many of his books deal with issues like immigration, borders, and Mexican-American history, Troncoso believes his work should appeal to non-Latino readers if those readers are interested in the conflicts of love, the dilemmas of family between the traditional and the modern, and the debates about what should be meaningful in life. “I think my topics are often philosophical or psychological in nature, and so they should have universal appeal, but I always pursue them through the lens of immigrants or residents of the border, because that’s my community”, he said.

Troncoso, who now lives in New York, where he teaches fiction and nonfiction at the Yale Writers’ Workshop, graduated magna cum laude from Harvard College and received two graduate degrees in international relations and philosophy from Yale University.

“Going to Harvard was an opportunity for me, and I took it,” the author said, when asked if he agrees with an education system that seems to leave behind minorities or kids with uneasy situations at home. “My situation was hard enough: we were dirt poor, and despite that poverty, I did well in school. Part of that was the discipline my parents taught me, and part of it was also the teachers who helped me as I did extra work,” Troncoso said.

STORIES FROM THE BORDER

After Harvard and Yale, Troncoso won a Fulbright scholarship to Mexico, where he studied economics, politics, and literature. He was inducted into the Hispanic Scholarship Fund’s Alumni Hall of Fame and the Texas Institute of Letters, a nonprofit honor society founded in 1936 to celebrate Texas literature and recognize distinctive literary achievement, of which he is now the outgoing president. Troncoso is also a member of PEN America, a writers’ organization protecting free expression and celebrating literature, and the Authors Guild, the nation’s oldest and largest professional organization of writers.

The idea of becoming a writer sparked when he was a student at Ysleta High School and editor of the school newspaper, the Pow Wow. “I thought I might be a journalist, but that’s as far as my ‘literary imagination’ allowed me. I didn’t know I could be a ‘fiction or nonfiction’ writer. I loved to argue and I enjoyed communicating complex topics in simple, direct language”, he recalled.

He became a writer “to tell the stories from the U.S.-Mexico border and to represent the characters of the border that were not seen in libraries, schools and bookstores. My motivation has never changed: I want the conversations, dilemmas and dramas that I discovered on the border to be part of literary history and literary debates”.

EMBRACING COMPLEXITY

For Troncoso, in the era of globalization, where borders are becoming meaningless and nationalism is on the rise, we all have a push-and-pull to choose sides all the time, between United States and Mexico, and between different political philosophies and ideologies.

RELATED CONTENT

“I think the thinking person does not just choose sides, that’s simplistic and is always fostered by social media to ‘like’ this or that. The thinking person creates her own unique self, her own unique side, and this is the essence of ‘nepantla’”, said Troncoso.

When asked why should a Philadelphia reader, Hispanic or not, be interested in reading his latest novel, the author replied that any Philly reader would love 'Nobody’s Pilgrims' if they’re interested in freedom and succeeding during difficult times. Regarding this, “The story pits Turi, Arnulfo, and Molly against problems they can’t control and problems they do control. They don’t belong with their families, and they are outsiders. Two of them are orphans, and the third is an undocumented immigrant. But they belong with each other. They are different from each other, with different values and perspectives, yet they forge a bond that allows them to risk their lives for each other. That’s how they survive." Troncoso believes that life in El Paso is better now for the Chicano or Mexican-American communities than it was when he was a child, but it is difficult to generalize this for the entire country, because each region is different.

“I think what you have seen is a growing Chicano/a middle class, a community that is spreading beyond the border to other parts like the Midwest or New England or rural places where traditionally we hadn’t seen many Mexican Americans. I think that’s one reason why sometimes you have instances of racism and xenophobia, because Mexican Americans are becoming more of the internal fabric of this country. The border is going beyond the border, so to speak.”

EDUCATION IS THE WAY

For Troncoso, the biggest challenge for Mexican-Americans is education: “We need to keep pushing the next generation not only to go and finish college but to strive for graduate and professional degrees. In my mind, education is power. Education is the road to being able to defend yourself and your community as a citizen. Education is a way to refine your voice and the way to be heard, either at the ballot box or in a literary novel. As every generation of Mexican Americans becomes more educated, you will also see a growing complexity in this community,” he said.

As a consequence of this process, it will become more and more difficult to say “this is how Mexican-Americans vote”, or “this is what they think politically or culturally”.

Troncoso is fluent in Spanish, both speaking and writing, as he lived in Mexico City for one year. Whenever he can, he has conversations in the language he learned from his parents, for whom he has great respect. “What I learned from my mother was to love reading and to keep to a code of ethics about how you treated people. She was muy católica, and I think that set of moral values was very important for her,” he said.

LEAVE A COMMENT: