Why truth is crucial in children's literature, according to a popular Latinx writer

Can we preserve a child's innocence while confronting them with the dilemmas of the world? For Matt de la Peña, author of Milo Imagines The World, the answer…

Every journey is more than just getting from one place to another. From the people we meet to the thoughts that assail us, they become part of the journey and affect us, sometimes in a profound way. Undoubtedly, so does our destination.

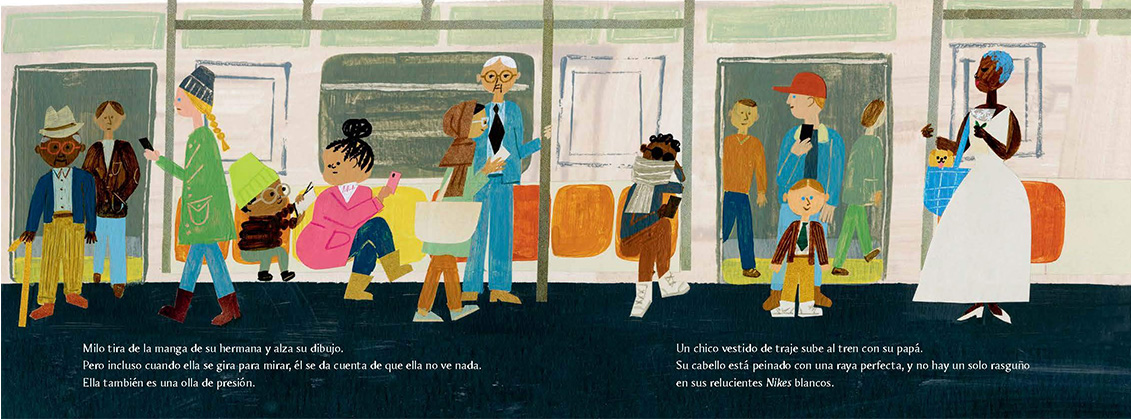

With a green hat and a pencil behind his ear, Milo sits on the metro with his sister watching people get on and off and inventing their stories, drawing them. Where are they going? Who are they?

Imagine the boy who has just entered in his smart suit and, in his head, Milo hears the clop-clop of a horse-drawn carriage. A castle and a moat, and butlers; he draws that too.

What we don't know, what runs under the skin of this story, underground like the underground, is that this little Latinx cartoonist is going to see his imprisoned mother.

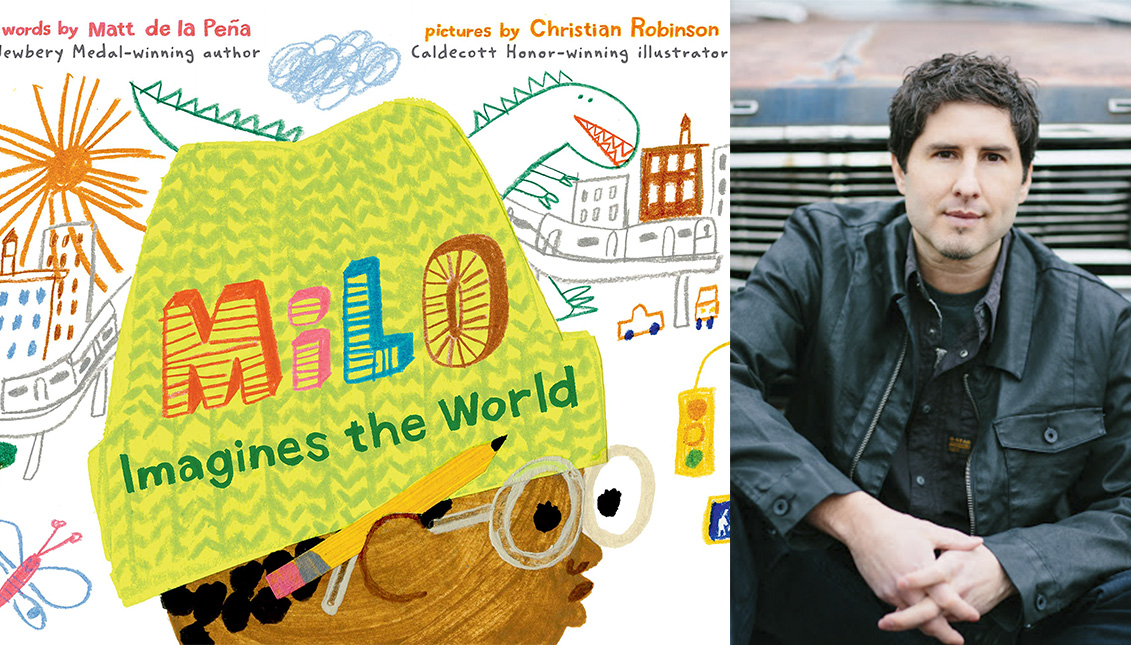

This is the catalyst for Milo Imagines The World, the new children's book by San Diego writer Matt de la Peña, who was the first Latinx to win the prestigious Newbery Medal in 2106 for Last Stop on Market Street, an illustrated children's story about inequality.

The long shadow of the award weighed on De la Peña's creativity for a while. He felt nauseous; he wondered if he would ever write anything worthy of a Newberry again, and, finally, he left the idea behind to do what he does best, tell stories to children that are full of truth even if it can be bitter.

"I think all creators of children's books have to ask themselves one question: what is my role in writing books for young children?" the writer tells Pacific San Diego.

"Is it to preserve innocence or to tell the truth? Because sometimes they don't fit perfectly, sometimes there's a dissonance. So I always prefer to lean towards the truth."

The theme of children like Milo facing the drama of having a parent imprisoned is not common in children's literature, but it is part of many young people's lives.

"I knew I wanted to explore a young boy with an incarcerated mother, but I wanted that to be on the margins of the story and not at the center of it," says De la Peña.

RELATED CONTENT

"One of the ways to tackle heavier themes with young readers is to put it in the margins, where it's kind of silent. Think of it like turning the volume up or down on a stereo: I turn down the volume on the heavy stuff, so it's there to be explored, but it's not the only thing to be explored," he adds.

While much of Matt de la Peña's books are based on fragments of his childhood, Milo Imagines The World is the story of his illustrator, Christian Robinson, growing up with an incarcerated mother and in the care of his grandmother.

"It was my dream to work on this with Christian because I knew it was an important story for him and for many children," says De la Peña.

"One of the ways to tackle heavier topics with young readers is to put it in the margins, where it's kind of silent."

Robinson is a regular collaborator on the Mexican American's stories. They have worked together on other books, such as Carmela Full of Wishes, an illustrated work inspired by the immigrant community of Watsonville, California, where De la Peña's parents moved.

"I love working with Christian. His art is so whimsical that when he illustrates my texts, it mitigates some of the heaviness," says the author, who teaches literature at San Diego State University. "I feel like I'm writing a spoken poem, and then when I give it to Christian, he turns it into a picture book."

The question of confronting children with these truth-laden stories that help them learn about their origins and understand systemic oppression, such as racism or inequality, has been a constant concern in Matt de la Peña's work — even a controversial one.

One of Matt's books for young people, Mexican WhiteBoy, which recounts the vicissitudes of a boy too "Mexican" for his neighborhood but not "Mexican" enough for his relatives, was banned in Arizona as part of an initiative to remove books promoting "racial resentment" from the Mexican American Studies Department of the Tucson Unified School District. Fortunately, the initiative was short-lived.

LEAVE A COMMENT: