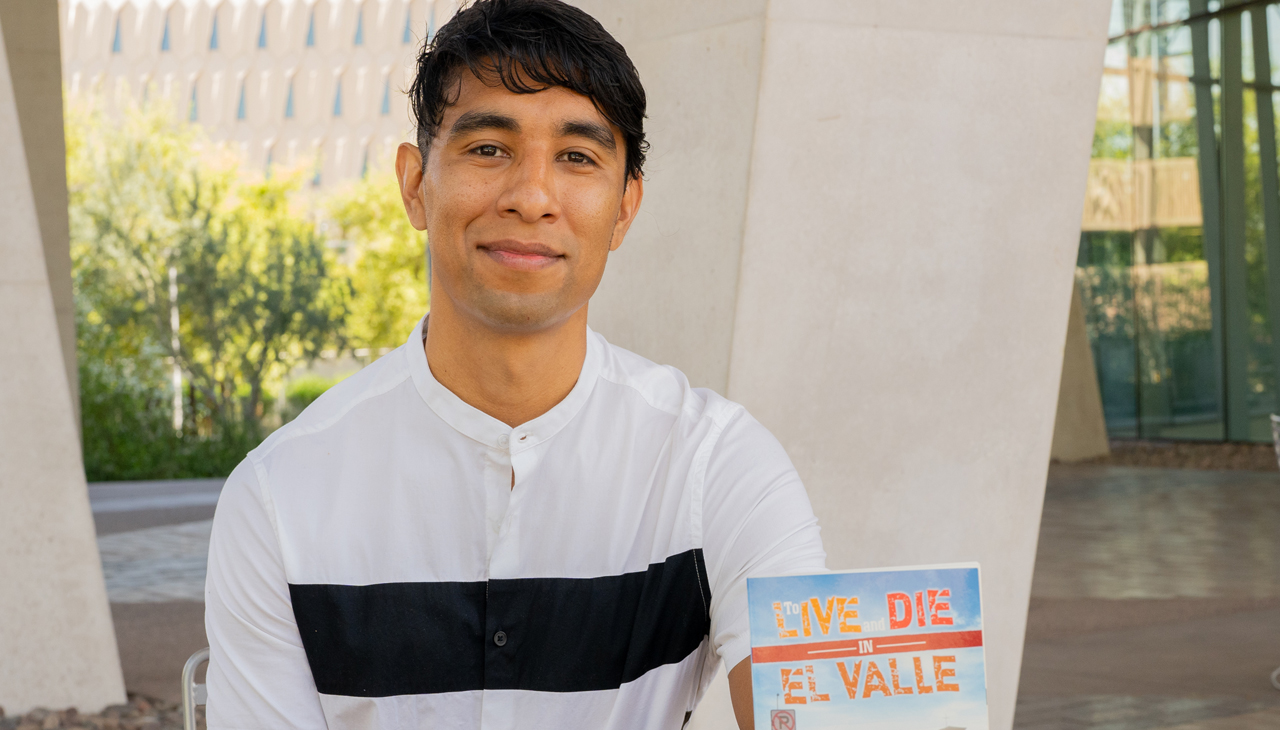

‘To Live and Die in El Valle’

Oscar Mancinas’ stories illuminate Hispanic and Indigenous experiences in the Southwest.

Oscar Mancinas grew up in Mesa, Arizona's third largest city near the Mexican border, and recalls loving to read as a child. However, when he tried to read local authors with Latino and Indigenous roots like himself, he felt they did not reflect the real life of his community. It was then that the doctoral student of Transborder Studies at Arizona State University (ASU) felt the impulse to write his latest book, To Live and Die in El Valle (Vivir y morir en El Valle, Arte Público Press, 2020) a collection of 13 fictional stories that describe the hard-working community of Hispanic and Native American origin in the U.S. Southwest and the harsh circumstances beyond their control that have shaped their lives, from emigration in search of a better life to centuries of systemic racism and colonialism.

Some of the characters in the book are young people who decide to leave El Valle "rather than have to live trapped in a place where you don't belong," Mancinas writes. But living far from home means having to deal with uncomfortable situations, as happens to one of the main characters, a student at a New England university, when he receives a call from the admissions office asking if he can give a faculty tour to a Mexican family. He accepts the proposal, but the interaction with the family serves as a reminder of his discomfort at having to deal with his Mexican identity and not finding a place on campus.

In the book — awarded two months ago with the Southwest Book Award given each year by the Border Regional Library Association, a nonprofit that promotes library service in the El Paso-Juárez cross-border metro — there are also young people who prefer to stay in Arizona. Such is the case with Kino, who strongly resists his friend's constant prodding to apply to an out-of-state college.

"You think I won't still be a wetback to people outside? You think I feel like being 'your little Indian friend’ on the East Coast? You think you're better than all of us here?" retorts Kino.

Mancinas also brings up those who live with the daily fear of deportation or the loss of family members in his book. This is the case of Fernanda, a young woman trying to adapt to her new life as an undocumented immigrant in El Valle, where the family ritual of baseball is the only thing that makes her feel a little comfortable. Another protagonist is Roach, a young man whose mother never told him that his father was deported just before he was born and he ends up finding out unexpectedly. Finally, there is Melissa, who will have to wait for the long car ride to college for her father to finally tell her about her older brother's death.

As described by her publisher, Arte Público Press, Mancinas' characters often struggle to find a sense of belonging, and their stories eloquently illuminate Hispanic and Native American experiences in the Southwest. Experiences very similar to those the author lived in his own skin and which he has wanted to capture in his first book of short stories years later.

AL DÍA News had the opportunity to talk with him about the day-to-day life of the Mexican-American community on the border and the influence his origins and established power structures have had when it comes to his writing.

You grew up in Mesa, Arizona, as a Latino-Chicano-Mexican-American? So many labels! Do you identify with any specific one?

There are lots of labels for us, it’s true! That’s the tricky thing about having connections to different traditions, peoples, and cultures. Each generation tries to come up with a more precise label for all of us, but each label has its own history of borders and exclusion. I identify with Latino, Latinx, Chicano, Chicanx, Mexican, Rarámuri, and Indigenous. Growing up in Mesa, I was fortunate to be surrounded by a community that cared for me and helped me keep ties to my cultures. Things weren’t always easy, we were working-class, and the racism around us was as strong then as it is now, but I grew up feeling proud of my community, my cultures, and my family.

Tell us a little bit about yourself. How did your parents' origins impact you and your understanding the world?

Both of my parents are immigrants from Mexico. My mom is a mestiza from Monterrey, Nuevo León and my dad is a Rarámuri from Chihuahua. They both migrated to Arizona to economically support themselves and our extended family. Because of this, I grew up with a strong sense of my belonging to different communities across the U.S.-Mexico border. My mom, especially, has always been a strong advocate for our communities. She participated in political campaigns, petitions, and protests. She knew life wasn’t going to be easy for us in this country, so she did her best to teach us to be vocal and respectful. It took me years to fully appreciate all the lessons she and my dad tried to teach us.

Did you always want to be a writer? Were there any writers in your family or nearby that served as an inspiration for you?

I always liked to read and to let my imagination take me to other worlds based on what I was reading. I think that’s a common trait for people who become authors. We start as kids who get lost in books and try to recreate some of those experiences from the other side. While I didn’t grow up with other writers in my family or in my neighborhood, I did grow up with family and neighbors who were great storytellers. From them, I learned how to craft stories and keep an audience interested in what I had to say.

You are a doctoral student in Transborder Studies. What does it mean to grow up in a borderland? What makes it different from growing up as a Latino in a big city like NY or Philadelphia?

Gloria Anzaldúa once wrote about the U.S.-Mexico border: “The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds,” and I think this is one of the most insightful observations not only about the specific international border but about borders in general. I don’t know what it’s like to grow up Latino in other cities, but I do think borderlands influence more people than just those of us who live a few hours from an international boundary. From talking to friends who grew up in cities in the northeast, I get the sense that they also experienced feeling like they belonged to multiple places but also that they had to hide some parts of their culture for protection. I think the last 30 years in the U.S. have made us all feel like we are una herida grating against the border and bleeding.

How did you come up with the idea of this book?

The idea for this book emerged when I was pursuing a Master’s degree in creative writing. Even though I had moved away from home, all of my story ideas were about neighborhoods like the one I had grown up in, and all the characters I thought of were similar to people I grew up with, who all tried to figure out where they belonged in their communities and outside of their communities. Eventually, this turned into stories all connected by the same fictional city in central Arizona.

The book is a collection of stories about working-class, non-white people who must carve out their own communities amid racist and classist exclusion. Are these stories based on your own personal experience?

RELATED CONTENT

Some stories are based on experiences I’ve had, and some are based on things I have observed or read about, but they are all fictionalized. Real life doesn’t fit into clean narratives, nor can it be explained with simple reasoning, so my stories differ quite a bit from my actual life.

In a past interview you said about your book: “I tried to add to our local literary traditions by including characters or cultural expressions which may not previously have been published by other Arizona authors." Can you give some examples?

Yeah, some of these examples include Rarámuri cultural expressions and characters — something that I haven’t previously seen in Arizona literary fiction. Other examples include stories about characters venturing out of Arizona and trying to find a place to belong in parts of Texas, Southern California, and New England. I also did my best to include the kinds of vernacular and slang I grew up around.

What do you hope readers from Philadelphia can take away from your book?

I hope anyone in Philadelphia who reads my book feels like they can also write stories about their communities, especially if they feel like they haven’t ever seen their community represented in literature.

Are you working on any new project now?

Yes! I’m working on my first full-length collection of poetry. It will be published later this year.

Would you like to see the book translated into Spanish?

Yes! I would love to see the book fully translated into Spanish. In fact, I tried to preserve some elements in a very common type of Spanish here in Arizona, things like dialogue and descriptions. I don't know when or how the book will be fully translated into Spanish, but I'm okay with the idea.

LEAVE A COMMENT: