'Infinite Country': Family is a Migrant's Homeland

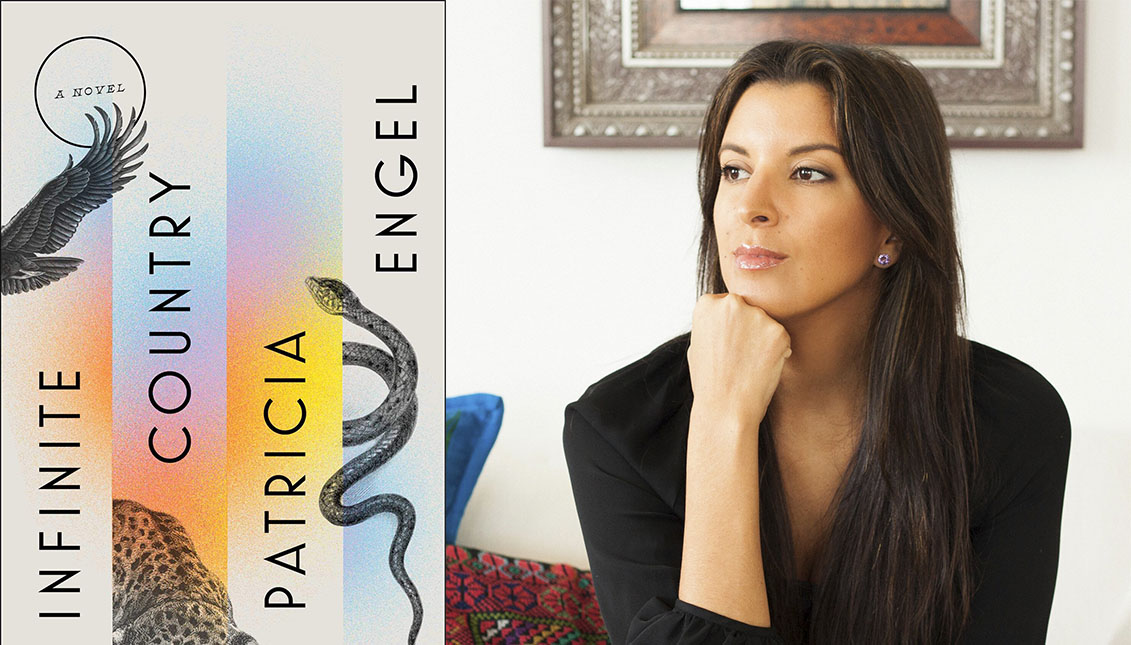

Colombian writer Patricia Engel's new novel follows the life of a family between two continents at the mercy of changing immigration policy.

The Russian writer Leo Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina: "All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

While no one's happiness or unhappiness can be summed up in a snapshot, we are all the sum of both — a collage of experiences that define us and feed our identity.

Like the family presented by Colombian novelist Patricia Engel's newest novel, Infinite Country (Avid Reader Press) — a celebrated novel published during Women's History Month — which narrate the life of several generations between two oceans, two cultural realities, and changing migratory regulations that sway them as the wind does with a reed, without ever breaking it.

The story begins with Elena and Mauro, a Colombian couple that obtain a tourist visa for the United States to escape from their country, not because they are directly threatened, but because they seek a better and much less violent future for their children, some of whom were born in Bogotá and some of whom will be born in the United States.

This is one of the feats of Infinite Country, its realism is not exempt of drama, but also not exempt of joy either. The way Engel portrays the daily life of some people from the 90s to the present to ask questions that many of us have asked ourselves once they are already settled in the United States. As when she writes:

RELATED CONTENT

“What was it about this country that kept everyone hostage to its fantasy?”

The reader, especially the Latino reader, finds in Infinite Country a mirror in which to see themselves reflected in the way both the characters and the dreams they pursue change according not only to their own progress or the obstacles they face as migrants, but also to the political and social context that leaps into the abyss of prejudice after the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

“This is a family who defines themselves as they are,” the author, a professor of creative writing at Miami University, said in an interview with NBC. “And the book asks the question, really, how does a family remain a family through distance and time and uncertainty, and ever changing immigration laws?”

Of Colombian parents but born in the United States, Engel drew from her own experience to write this story, though rather than catering to some political agenda her remit was to "serve the truth."

“I come from a very large, large family, that happened to be located — a lot of them — in the United States, but a lot of them had complicated immigration situations,” she said. “And a lot of people close to me, a lot of my dearest relationships, the people I love, most of those worlds, often were challenged by legal circumstances related to their, you know, paper status in this country.”

The bitterness of family separation and deportations, racism and prejudice and bureaucracy creep into this costumbrist and sometimes heartbreaking tale that is heavily marked by nostalgia for origin nurtured over time, assimilation to a new, unfamiliar home and the sense that there is often no homeland but one's own family.

“I think that's something that first- and second-generation families who are newly arrived in the United States feel in a very vivid way,” Engel said, “that when you've lost your homeland, or you are far from your homeland, and you're in an unfamiliar place — certainly I felt this growing up — that my family was my country, my family was my homeland, who we were in our home was different from the world outside the door,” the author concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: