Eighty years without James Joyce: Translating "the untranslatable"

In 2016, Marcelo Zabaloy, an Argentinean computer technician, made the first Spanish translation of the labyrinthine Finnegans Wake.

Jan. 13 marks the 80th anniversary of the death of Irish literary master James Joyce, who always lived outside his native Dublin and is recognized as the father of a literary vanguard that heavily-influenced the writers of the Latin American boom.

Works such as Ulysses, of which it is said that Joyce wrote as a joke for his friends and the flow of thoughts is more like a waterfall that has caused generations of discussion. Few have finished reading it, and it has passed into the annals of literature for experimentation.

Because Joyce, unlike many other authors, considered writing as an art and not as a profession.

However, among all his books there is one that has the reputation of being the scourge of the most seasoned translators and was even considered "impossible" at one point.

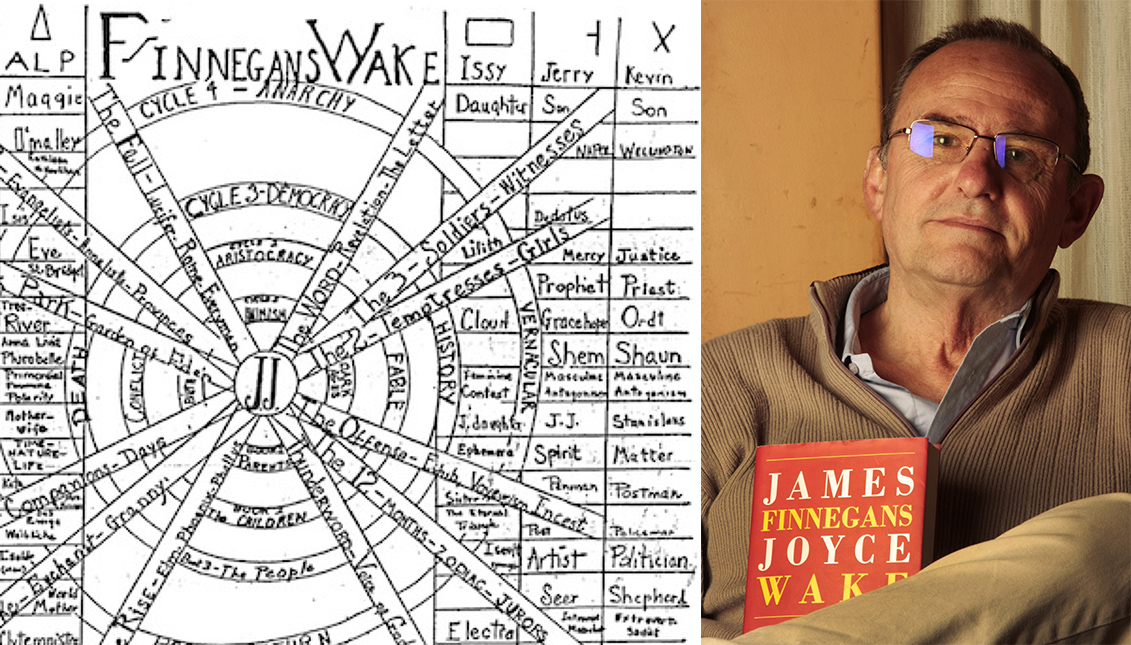

It is Finnegans Wake, a very complex text full of tongue twisters, onomatopoeias, invented words and unthinkable retranslations that tells us the mother of all epics and the history of all stories in a circular structure. The story of the death and awakening of Tim Finnegan (who the title refers to), is also the protagonist of an ancient Celtic ballad, and of his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle, their children Shem and Shaun — writer and letter carrier, respectively — and a young woman in dispute, Iseut.

From there on, a quagmire of plots opens and keeps multiplying, as if the reader became the protagonist of Borges' tale, The Garden of the Forking Paths.

All of it is contained on more than 600 pages.

For a long time, Joyce's Hispanic followers gathered around Finnegans Wake in its original version as if it were a sort of Mayan codex, trying to decrypt its symbols, as shown in Dora García's colossal documentary The Joycean Society.

However, there was one man who, with no training as a translator, nothing but his great bookish voracity, embarked on the maddening enterprise of bringing Finnegans to the Spanish-speaking world.

The Argentine Marcelo Zabaloy is not afraid of challenges. He worked all his life repairing computers and installing computer networks, far from the literary world except for his passion for reading. Until 2004, when his wife gifted him with an English version of Joyce's Ulysses.

It took him a year to read the whole thing and since he couldn't understand the meaning of all the sentences, instead of getting cold feet, he said to himself: "What if I translate it to find out better?"

Zabaloy collected dictionaries, essays, reference books... Until his wife gave him another gift, a French edition of Ulysses, the translation of which was supervised by the author himself.

With all these tools, he managed to get the Argentine publishing house El Cuenco de Plata to publish his version of Ulysses — the first translation of Ulysses into Spanish was done by José Salas Subirat, an Argentine insurance agent who had written a couple novels.

Then came Finnegans Wake.

"It was a task to be done alone or not at all," Zabaloy told La Voz.

The self-taught translator took seven years (2009-2016) to undertake the task of immersing himself in the labyrinth where language is also part of the dream proposed by Joyce.

Especially because of the 450 words printed on each page, at least a hundred seem to lead to a dead end, or have infinite meanings.

"Nothing in Finnegans Wake is what it seems, everything has double, triple or multiple meanings," added the translator, who managed to turn his version into an original of the original, decrypting line by line and trying to make all the pages start and end with the same words in English and Spanish.

"It is the optical illusion of an impossible translation, it is literally impossible. That is the spirit of Finnegans Wake. It's phenomenal, monumental nonsense," he said.

Following in the footsteps of Joyce, who never added a single note to this enigmatic book, Zabaloy decided not to incorporate explanations so as not to turn it into a brick of thousands of pages and proposed that the reader confront Finnegans with the look of a newcomer to the world:

"It is to be read in homeopathic doses, open it in half and read one page and at the same time go back and grab another. It does not support or resist, nor is it advisable to read in a linear fashion. You don't have to go off and read it, not even like Ulysses, because it frustrates you immediately. But if you go pecking little by little you suddenly find epiphanies, luminous oases," he recommended.

"Nothing in Finnegans Wake is what it seems, everything has double, triple or multiple meanings."

Without a plot or a story that can be told, making a dozen versions until the final text is reached, Zabaloy's Finnegans Wake is almost a new Finnegans in itself —"it's as if you had a shed at home and someone brought you a bag with a hundred kilos of puzzles," he told Clarín.

"And of the hundred kilos you have thirty of a grey that varies from one end to the other, in a hundred scales. Where the floor, the ceiling and the sea are the same and each piece has to be put together correctly."

It's a dream book with its absurd passages and other clear ones, which escape or are repeated over and over again on the banks of the same river.

A colossal adventure that melts your brain.

LEAVE A COMMENT: