'Educating the Enemy': How the U.S Educated the Children of Nazis and Mexicans during Cold War

New book compares the education given to children of Nazis and Mexican Americans in Texas after World War Two.

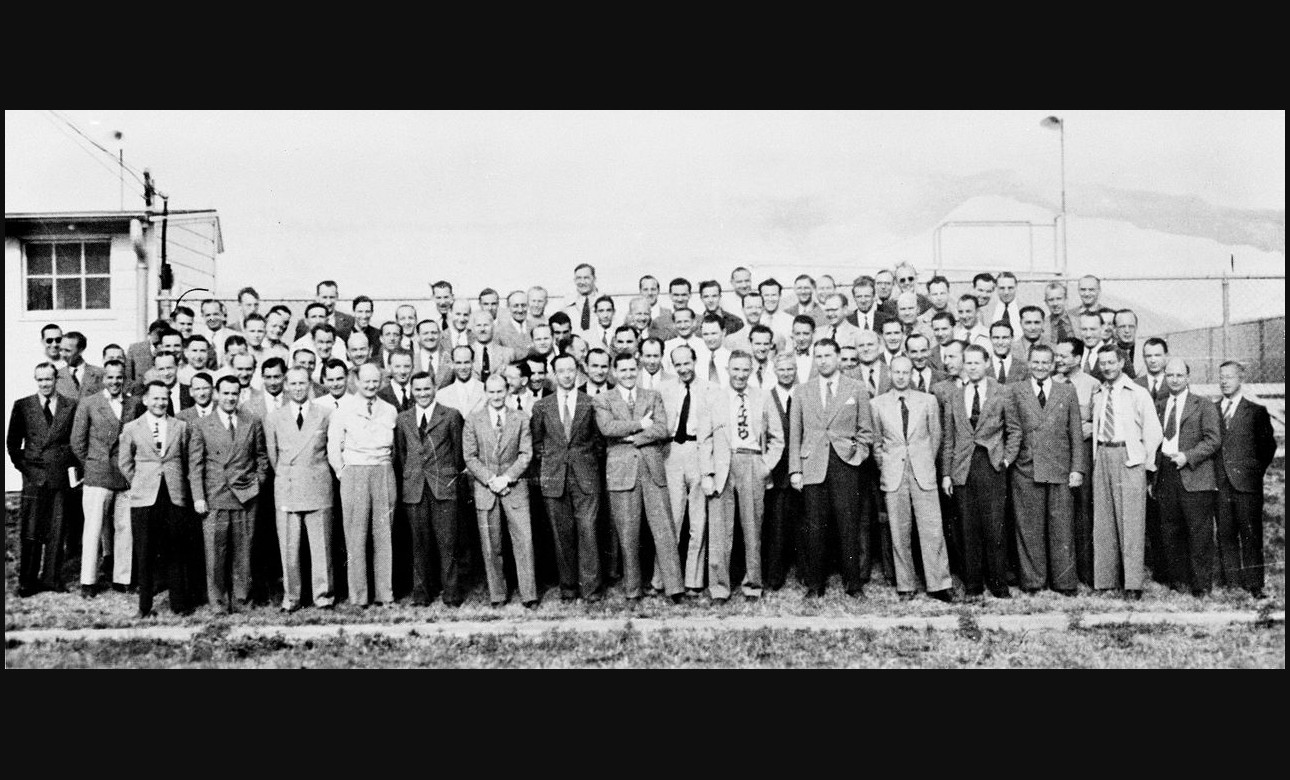

Between 1946 and 1947, a group of leading Nazi scientists and their families relocated to El Paso, Texas, as part of the military program called Operation Paperclip, in order to work on missile development during the height of the Cold War with the U.S.S.R.

The 144 children of this Nazi scientists were bused daily from a military outpost to four El Paso public schools. Though born into a fascist enemy nation, the German children were quickly integrated into the schools and, by proxy, American society. Their rapid assimilation offered evidence that American public schools played a vital role in ensuring the victory of democracy over fascism.

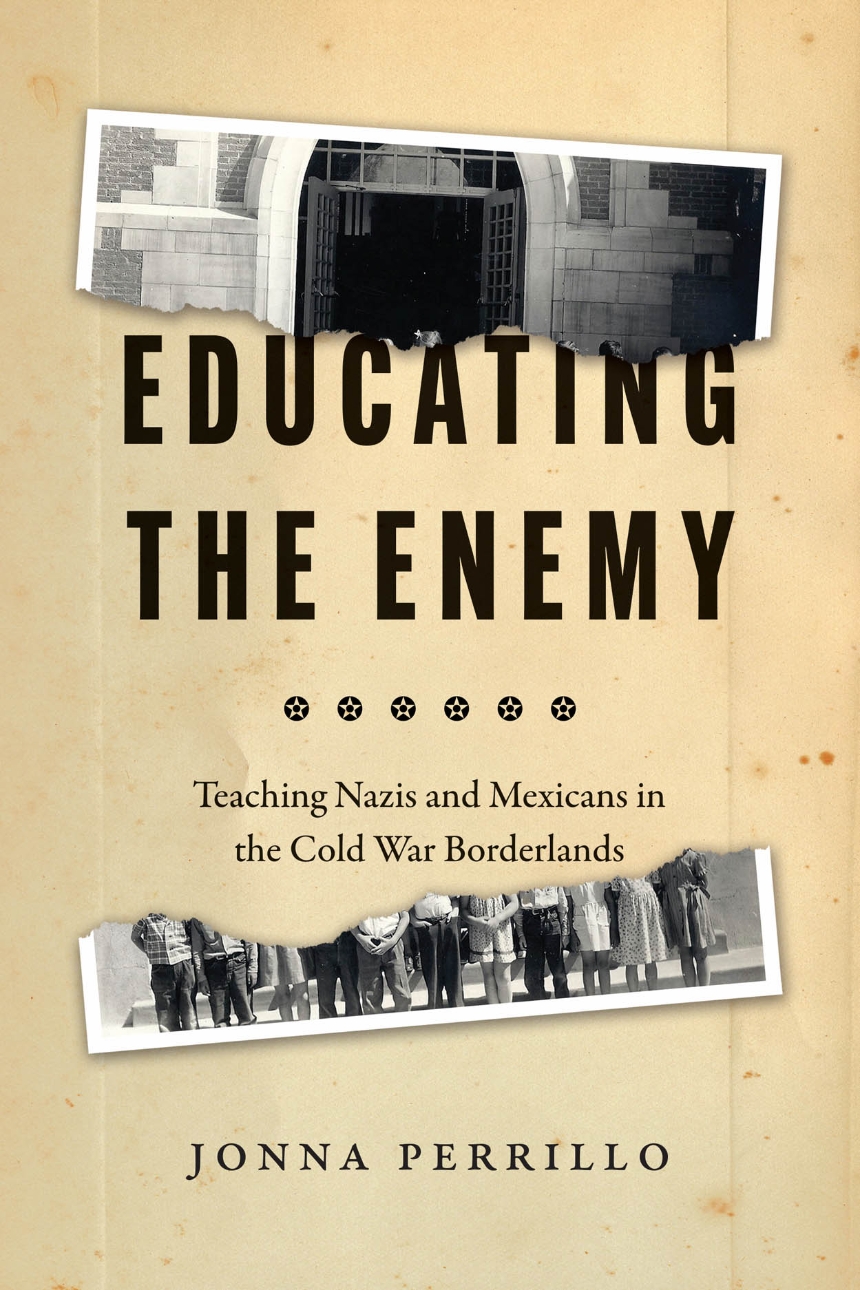

In a new book, 'Educating the Enemy: Teaching Nazis and Mexicans in the Cold War Borderlands', Jonna Perrillo, associate professor of English education at the University of Texas at El Paso, not only tells this fascinating story of Cold War educational policy (including how the U.S. used these children as propaganda tools) but she draws an important contrast with another, much more numerous population of children in the El Paso public schools: Mexican Americans.

RELATED CONTENT

Like everywhere else in the Southwest, Mexican American children in El Paso were segregated into “Mexican” schools, where the children received a vastly different educational experience. Not only were they penalized for speaking Spanish—the only language all but a few spoke due to segregation—they were tracked for low-wage and low-prestige careers, with limited opportunities for economic success.

As Perrillo explained in an interview with TIME magazine, The El Paso school system was over 60% Mexican American at the time—a majority of the city’s public school population. There were two kinds of schools in El Paso, and this was familiar nomenclature throughout the Southwest: what were called “American schools” and “Mexican schools.” American schools were schools to which white children were assigned; Mexican-American students were sent to Mexican schools. The German children were sent to American schools.

“America had a vested interest in assimilating the German students to testify to the ability of American public schools. But there wasn’t the same vested interest in assimilating Mexican-Americans and in educating them. The expectation was conveyed to them very early on that they were a drain, an economic burden, and kind of a social burden,”, Perrillo told TIME. At the same time, they were also seen as competitors; there was this underlying anxiety over these people that white Americans saw as inferior, but had the potential to take jobs from them. “This history is so important for us to understand because of the way in which, both historically and in contemporary life, we treat different groups of students fundamentally differently,” she concluded.

As their editors at University of Chicago put it, "'Educating the Enemy' charts what two groups of children—one that might have been considered the enemy, the other that was treated as such—reveal about the ways political assimilation has been treated by schools as an easier, more viable project than racial or ethnic assimilation."

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.