Edgar Allan Poe: A Rediscovered Face in a Gentrified Philadelphia

"I NEVER knew anyone so keenly alive to a joke as the king was. He seemed to live only for joking. To tell a good story of the joke kind, and to tell it well,…

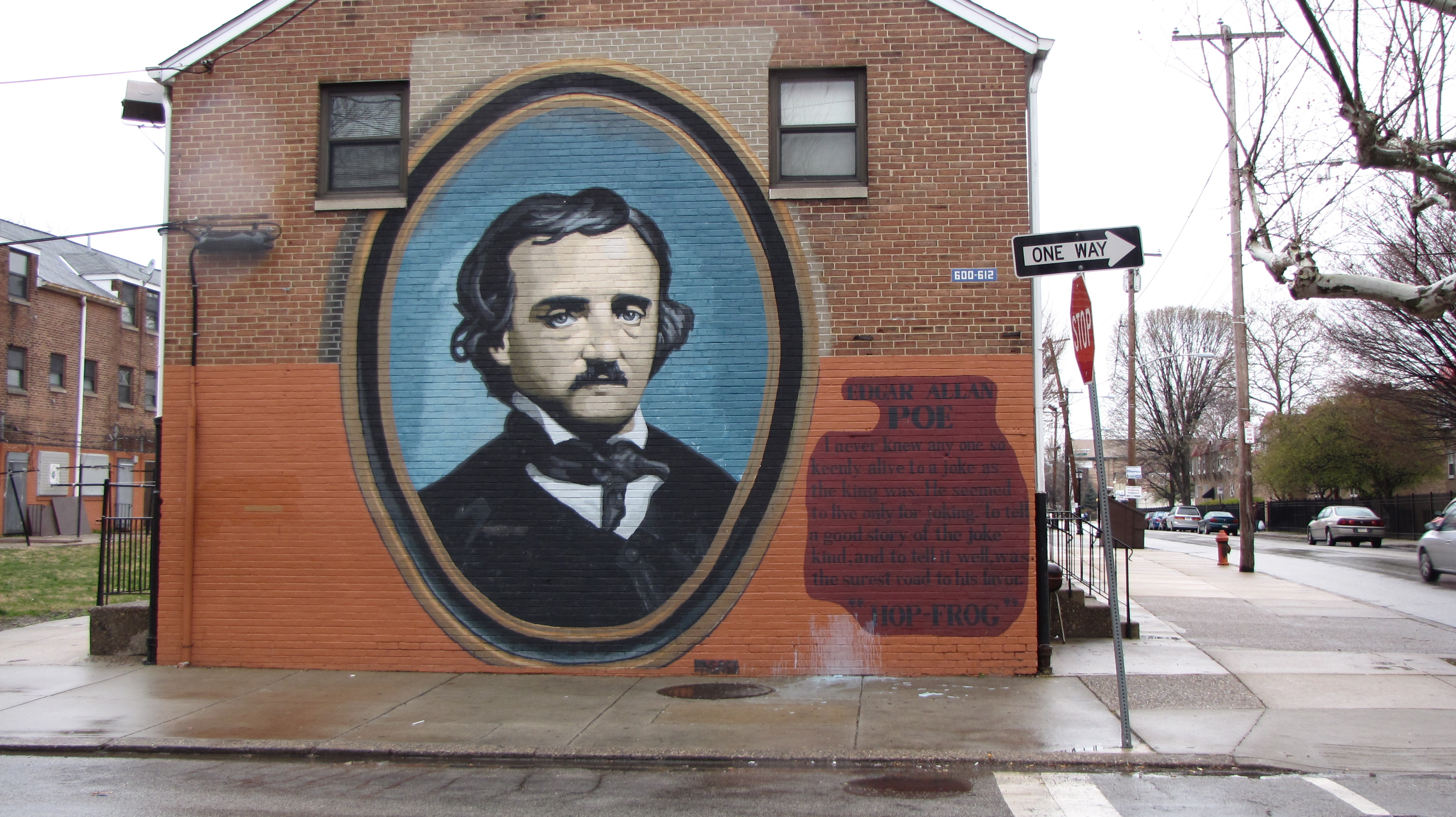

“Thanks” to gentrification (in-between quotation marks, as the aforementioned process is one that tends to emit sensitivities and controversy), the profile of one monumentally important literary figure has resuscitated in the most unlikely of places. In the tell-tale heart of Liberties West, formerly known as another gritty chunk of the Olde Kensington township, a mural and a home have withstood the tides of change, and so the presence of Edgar Allan Poe in Philadelphia lives on, albeit way below the radar since the 1970s.

For those of you poetry buffs and “Ravenheads” that are incredulously perplexed at the notion of Poe being memorialized in Philadelphia, much less right off the beaten track of Spring Garden Avenue, it’s true. You may have not known of this significant piece of Poe’s history because the establishment itself, a national park and national historic site comprised of a museum and a house that Poe lived in for roughly six years, was in an area that neither tourists nor locals (a park ranger admitted to me) normally ventured to. Racial tension and impoverished socioeconomic conditions fenced-in Poe’s literary contributions in Philadelphia, leaving knowledge of the national park to only the most fanatical of poetry buffs (most being international visitors).

In an article written by Max Marin for Hidden City Philadelphia in March of 2016, a lifetime resident of 7th and Spring Avenue, Frank Taylor, gave insight on how the face and the persona of Poe shaped his childhood growing up in a turbulent decade. During the piece, he mentions how he and his friends used to climb the roofs of the projects to grasp the apples that grew in Poe’s backyard to have fruit for the day, and even states that “Poe” became synonymous with “hoodlum” and “cool badass” in his neighborhood.

The irony of it all is that the face of Poe and the physicality of his home also represent volumes of a multitude of racist, pro-slavery, anti-abolitionist, insensitive and caricaturistic writings, one of which is (perhaps ignorantly and without malicious intention) quoted on a grandiose mural featuring the bust of Edgar Allan Poe to the side of the house museum. “Hop-Frog or The Eight-Chained Ourang-Outangs,” which compares African Americans to orangutans (a trope common in nineteenth century literature), is a story that is teeming with Poe's anti-black mentality, one that was prevalent throughout many a figure during his time, literary and ordinary alike. Even though the Mural Arts Program of Philadelphia did have the foresight to not include the following types of passages on the poet’s visual likeness, this does not excuse that the story makes an appearance in a predominantly African-American borough:

“The chains are for the purpose of increasing the confusion by their jangling. You are supposed to have escaped, en masse, from your keepers. Your majesty cannot conceive the effect produced, at a masquerade, by eight chained ourang-outangs, imagined to be real ones by most of the company; and rushing in with savage cries, among the crowd of delicately and gorgeously habited men and women. The contrast is inimitable!”

Marin asked Taylor whether or not he would have felt upset if he knew that Poe was anti-black, but he retorted with frankness, saying that it would not have made a difference then or now, as he and his community were only concerned during the 60s and 70s with the macabre violence of the KKK and race riots. For the residents of then and now, Poe’s biography and stance on slavery was not worthy of preoccupation when they had the issue of civil rights to clench their fists over.

Thus, like most of Poe’s own work and life, the site on 532 North 7th Street remained occult and grimly mystified for most native Philadelphians-- until now.

The National Park hopes to engage with the community more, both throughout the outskirts of Philadelphia and on its block, by offering free admission on the weekends, free guided tours, school group reservations, and a Junior Park Ranger Program. Marin points out in his piece that the historical site could be doing more to be inclusive of its neighbors, and to admit to more of Poe’s racism to the public someplace in the exhibit. Rather than shying away from the human and historically contextualized flaws of Poe, the public and the National Park Service can actively become more socially aware together, bridging the wrongs of the past with the hopes of the future, by rooting the community in the work that needs to be done in the present to bring forth visibility to the issue of racism that still prevails, centuries later, in Philadelphia.

But, that was in March, and this is now. In the midst of crisp autumn leaves, candy-corn sales, and a heavily divisive electoral race, the museum hopes to bring some creepy cheer back to the city. Two park rangers, by the names of Ali and Stewart, gleefully informed that The Edgar Allan Poe House & Museum is finally up-and-coming, as the borough in which it is in is being transformed into a yuppie and hipster haven, and although both understood the negative connotations of gentrification, it was undeniable that the effect was a positive one for the prosperity of the site.

Repairs are nearly complete to the roof that was once over Poe’s head, the humble home receives about a hundred or more visitors each day that it is open (weekends only), and the site is even hosting in-conjunction with the German Society of Pennsylvania an Edgar Allan Poe Arts Festival. The festival appropriately takes place on October 28th of Halloween weekend to celebrate the lurid and haunted verses of the poet with a costume contest, beer and sausage, performances, themed-music, readings, and special guest appearances. While the park is typically free, this night costs 10 bucks a person, but it’s all worth it to hear the raven quoth again.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.