Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre: "There will always be a population that will refer to me as Latino"

‘The Displaced’ tells the story of a Latino working-class neighborhood threatened by gentrification

Rodrigo Ribera d’Ebre grew up near the LAX airport in the West Side of Los Angeles, also known as the LAX Coastal Region. The neighborhood he grew up in was, and still is, considered a typical Mexican and Mexican-American barrio, with traditional businesses that cater to an immigrant population. His parents immigrated from the state of Jalisco, Mexico to that area, and in the era he grew up in — the 80s and 90s — he participated in many types of cultural experiences such as skating, graffiti, post-punk, punk rock, street gangs, drugs, and gangster rap.

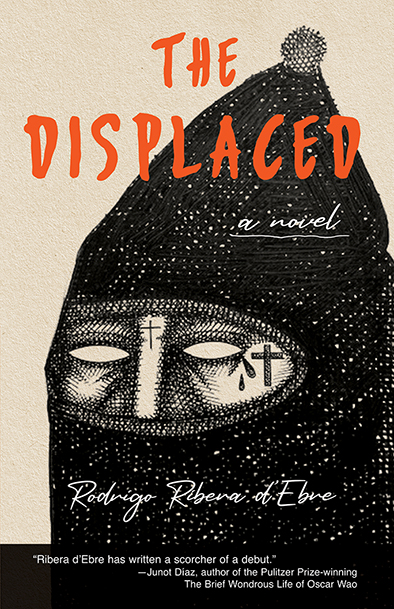

All these cultural elements made their way into his first novel The Displaced , which was released on June 30 by Arte Público Press. Set on the Westside of Los Angeles in 1999, The Displaced tells the story of a primarily Latino working-class neighborhood — already polarized by street violence between rival gangs — made even more uneasy by the looming threat of Y2K and gentrification, a phenomenon that still poses a threat for many long-standing communities in urban areas all over the country.

“Although I prefer to be considered an American writer/filmmaker, there will always be a population that will refer to me as Latino, as other, or as something else that makes sense to them,” Ribera d’Ebre told AL DIA News in a recent email interview. “For some Latinx people,” he added, “it might be more comfortable for them to label me as Latino as a form of empowerment, while some outside of the culture might assign me that label because it will make sense to them to see me as such, or as other. I lived in Latin America for four years and I was very much considered an American.”

A plague of newcomers

Part coming-of-age novel and part dystopian thriller, The Displaced explores the friendship between Mikey, a recent UCLA PolySci grad who loves bands like The Cure and The Jesus and Mary Chain, and his next-door neighbor Lurch, a Culver City gang leader who loves the hood — its projects, beat-up apartments and crackheads — more than his own life. Determined to make a “difference” in the world, Mikey gets a job at the local paper and starts covering plans for “remaking” the neighborhood into Silicon Beach. Ironically, he makes the job connection via one of the new transplants to the area, a white guy named Mark who likes the same music, and his friend Stan, another local and “misfit” like Mikey who has no interest in gang life and would rather spend time skating and taking photos.

Meanwhile, Lurch is noticing more and more transplants like Mark, white people with beards, hipsters wearing V-neck sweaters and plaid shirts, running in jogging outfits or riding bikes with helmets, oblivious to the gangbangers. They’re artists, students, developers and entrepreneurs. Lurch sees them as a plague pushing people out of their homes. Together, the two decide they must fight back against this plague of newcomers and form a militia of locals and gangsters.

In the novel, the street violence is geared toward a different population: the gentrifiers

“Although I experienced street gang rivalries growing up, in the novel, the street violence is geared toward a different population: the gentrifiers,” Ribera D’Ebre explained. “I conjured up a fictional world where these street gangs could instead use all of their street and combat skills and create a pseudo-militia, because if they lose their neighborhood, there will not be a neighborhood left to fight for. So, most of the story is based on speculative fiction, and the alarmist tone of the book is based on years and years of reading about, examining, and learning about gentrification and urban planning.”

Ribera d’Ebre’s family did not experience the effects of gentrification in the neighborhood in which they grew up, but as an adult, when he first got involved in real estate, “I was priced-out of neighborhoods where I wanted to buy a home,” he remembered.

“And in the neighborhood where I did eventually buy my second home, it began going through a gentrification process and some of those experiences as a buyer/seller did make it into the novel,” he continued.

Exposing injustices

As a writer, he also wanted to explore issues of systemic racism, poverty, gang violence, drugs, etc. all of which he has experienced as well.

“And yes, those problems still do exist today, which I think is what will make the book relatable to certain people. And just because I don't experience it personally today, does not mean it doesn't still exist. You can drive through many communities in Los Angeles and visibly see all the above mentioned. And while I did grow up in one of the most economically-disadvantaged and marginalized communities in Los Angeles, I now live in one of the wealthiest suburbs in Los Angeles. Everyday I have gratitude for my trajectory,” said Ribera d'Ebre.

The fact that one of the main characters happens to become an investigative journalist was a way of honoring the profession and championing the work it takes to write an objective story.

“However, I also explore the character's shortcomings, which is that even when you try to be as objective as possible, subjectivity often gets the best of us. I simply wanted to show this nuance as a human flaw, so even when you attempt to be a watchdog of democracy, our biases can also guide us in certain directions. But I still have faith in journalism, yes!” he added.

RELATED CONTENT

I now live in one of the wealthiest suburbs in Los Angeles. Everyday I have gratitude for my trajectory.

A regular contributor for the Huffington Post, Ribera d’Ebre says he has always been a writer.

“I wrote poetry as a kid, rap music as a teenager, and moved on to non-fiction/essays at the university,” he explained.

The first manuscript-length work he wrote was philosophy.

“At first, I wrote because I felt like I had a message for the world, back in my early utopian coming-of-age days, but nowadays I write because I don't know how to do anything else.”

Think locally, act globally

Although the novel is set in a Latino community of Los Angeles, The Displaced is meant to a wider audience.

“'Think locally, act globally,' is what guided the narrative,” he said.

The book is directly informed by Albert Camus' The Plague (the original title of his novel was: The Plague @ Silicon Beach), as he explores some of the issues that Camus did.

“So, if Camus' fictional plague story based in the port town of Oran, Algeria can have a deep impact on someone like myself, then I think The Displaced can have an impact on people in different parts of the world.”

Ribera d’Ebre holds an MFA in Creative Writing and his work has been featured in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Design LA Magazine, Juxtapoz, Joyland and other publications. He is also a film and documentary director.

“For film, it came naturally for me to do documentaries because of my experience in nonfiction writing. So, in a way it's like a toolbox. I come up with an idea, and I choose whatever medium suits the story the best: essay, short story, novel, screenplay, documentary, or art show,” he concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: